High in the crags of Europe’s mountain ranges, where clouds brush against ancient stone and winds howl through cavern mouths, the Bearded Vulture builds its home. These nests, massive and stubbornly resilient, are not just places where chicks are raised and fledged. They are living archives—repositories of natural history, cultural relics, and fragments of human life spanning centuries. Unlike many birds that build a new nest each year, Bearded Vultures and other large raptors often return to the same one, generation after generation. If the site remains safe, a nest can endure for hundreds of years, expanding as each pair of birds adds new branches, bones, and materials to its structure.

It is within these timeworn nests that an extraordinary discovery was made: a window not only into the ecology of vultures, but also into the history of human cultures that once shared their mountains.

Nests That Last for Centuries

The Bearded Vulture, Gypaetus barbatus, is among the most remarkable raptors in Europe. With a wingspan that can stretch nearly three meters, it glides over the Pyrenees and other rugged ranges, searching for food. Its diet is unusual, consisting largely of bones, which the bird drops from great heights to crack them open and feast on the marrow inside. But its nesting behavior is equally fascinating.

Unlike smaller birds that weave delicate nests of grass and twigs that seldom survive a single season, Bearded Vultures construct fortress-like platforms in cliffside caves and rocky ledges. Over time, these nests accumulate layer upon layer of material. Generations of birds contribute to them, and so they grow into monumental structures, preserved by the cool, dry, and stable conditions of their mountain homes. Some of these nests, tucked safely away in caves and rock shelters, endure for centuries, becoming what researchers have called “natural museums.”

A Scientific Excavation

Between 2008 and 2014, researchers in Spain embarked on an unusual project. Their focus was on Bearded Vulture nests in southern Spain, where the species became extinct about 70 to 130 years ago. Of the many preserved nests found, 12 were carefully examined, layer by layer, much like an archaeological dig. The scientists applied the methods of stratigraphy—the same techniques used to uncover ancient human settlements—because these nests, in a very real sense, were historical archives.

The excavation revealed centuries of accumulated life: eggshells of vultures long gone, bones from their prey, and nesting materials both natural and artificial. As the researchers sifted through the remains, they began to uncover something astonishing. Among the feathers and bones, they found artifacts—objects crafted or used by humans, preserved by the nest for centuries.

Human Artifacts Hidden in Bird Nests

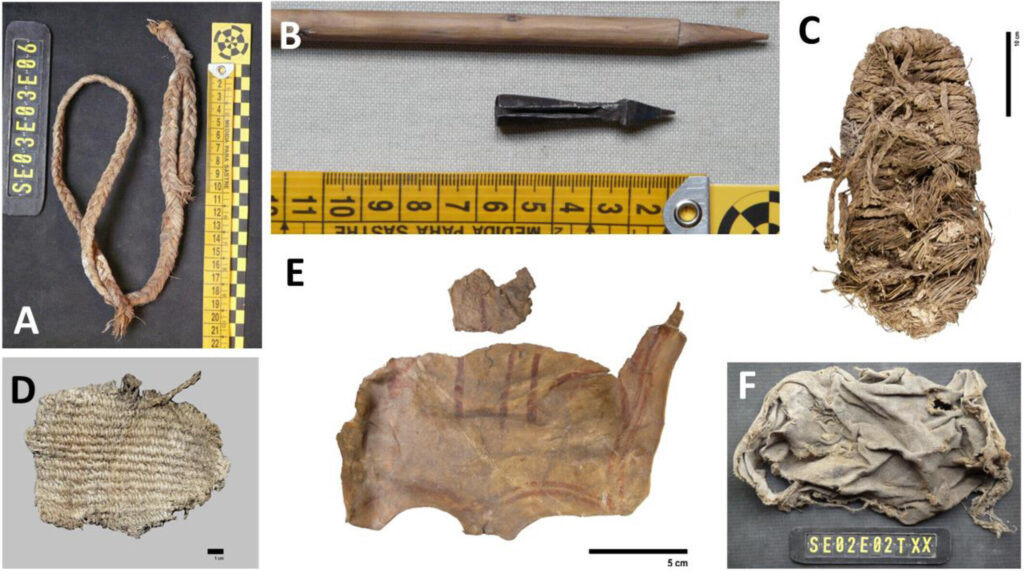

In total, 226 human-made items were discovered across the 12 nests. Each artifact carried with it a story, a glimpse into the people who once lived in the same landscapes as these birds. There was a slingshot made from esparto grass, a shoe, a decorated piece of sheep leather, a wooden lance, and even a crossbow bolt. These were not just scraps of trash; they were objects that had once belonged to lives lived hundreds of years ago.

Carbon-14 dating revealed that some of these relics were astonishingly old. A shoe dated back approximately 675 years, and a piece of decorated leather was about 650 years old. Other items, such as a fragment of basketry, were much younger, around 150 years old. Taken together, they showed that the vultures’ nests had preserved a layered record of human presence in these mountains, spanning across the centuries.

Natural Museums of the Mountains

What made this preservation possible? The answer lies in both the design of the nests and the environment in which they are found. Bearded Vultures build in cliff caves and rock shelters, places where temperature and humidity remain relatively stable year-round. In such conditions, organic materials that would normally decay survive astonishingly well. Leather, wood, grass, and fabric were found in surprisingly good condition, protected from the elements and preserved by time.

The researchers described the nests as “natural museums”—inadvertent curators of both natural and human history. Just as an archaeological site preserves the story of ancient civilizations, these nests preserved the overlapping lives of birds and humans in shared landscapes.

What the Bones Reveal

In addition to human artifacts, the nests contained vast numbers of animal remains. The study cataloged 2,117 bones, 86 hooves, 72 pieces of leather, 11 hair samples, and 43 eggshells. These were more than just random debris. They painted a picture of the birds’ diet across centuries and offered clues about the ecosystems in which they lived.

The bones included remains of both wild and domestic animals, suggesting that Bearded Vultures fed on carcasses left behind by pastoralists as well as wild prey. By examining these materials, scientists could trace changes in the local biodiversity, shifts in livestock management, and even environmental changes over time. The nests, in other words, were not only historical records of human artifacts but also biological archives of ecosystems long gone.

Bridging Human and Natural History

The convergence of bird behavior and human culture in these nests is profoundly moving. Here are vultures, unknowingly preserving relics of shepherds, hunters, and villagers who lived centuries ago. A child’s discarded shoe, a hunter’s broken weapon, a shepherd’s woven tool—all carried into the cliffs by a bird seeking to build a nest strong enough to last. In doing so, the vulture gave these objects a second life, protecting them in its fortress of twigs, bones, and branches.

The discovery is a reminder of how intertwined human history is with the natural world. We often think of ourselves as separate from nature, yet here is proof that our lives have been woven into the fabric of other species’ behaviors in ways we could not have imagined.

Lessons for the Future

These findings are not only of historical interest. They carry practical implications for conservation and ecology. By studying the preserved remains, scientists can learn about shifts in ecosystems, changes in species diversity, and the interactions between wildlife and human societies over time. Such insights are invaluable for conservation planning, particularly in efforts to restore habitats or reintroduce species like the Bearded Vulture to regions where they have vanished.

Moreover, the study underscores the importance of preserving the birds themselves. As a threatened species, the Bearded Vulture faces pressures from habitat loss, poisoning, and disturbance. Protecting their nesting sites means not only ensuring the survival of an extraordinary bird but also safeguarding these remarkable time capsules of history.

A Symbol of Continuity

The story of the Bearded Vulture’s nests is one of continuity and resilience. Across centuries, as empires rose and fell, as cultures changed and landscapes transformed, these birds returned to their cliffside homes, faithfully adding to the same nests. In their persistence, they created something far larger than themselves: archives that bridge the divide between nature and humanity, past and present.

There is something deeply poetic in the idea that a bird, without intention or awareness, has acted as a guardian of history. Each twig, each bone, each piece of human life it carried to its nest became part of a story much larger than the act itself. In the end, the Bearded Vulture is not only a scavenger of bones—it is a keeper of memory, a silent historian of the mountains.

Conclusion

The discovery of centuries-old artifacts within Bearded Vulture nests reminds us that the world is filled with unexpected intersections between human and natural history. These nests are not just structures of survival; they are monuments to coexistence, resilience, and time.

As we study them, we learn not only about birds and ecosystems but about ourselves—our ancestors, our cultures, and our place in a shared world. The Bearded Vulture’s nest, layered with centuries of life, teaches us that history is not confined to books or ruins. Sometimes, it waits in the cliffs, guarded by wings that have spanned generations, holding secrets until we are ready to listen.

More information: Antoni Margalida et al, The Bearded Vulture as an accumulator of historical remains: Insights for future ecological and biocultural studies, Ecology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ecy.70191