Beneath layers of time, before cities rose or languages formed, before fire was fully mastered, a human being walked across soft, wet ground. They may have been barefoot, perhaps holding the hand of a child. Or maybe they were alone, stepping carefully around puddles, glancing skyward at a sky no one would ever record. What they left behind wasn’t meant to endure—but by some miracle, it did. Imprinted in sediment and buried beneath volcanic ash or windblown dust, their footprints became a message across millennia.

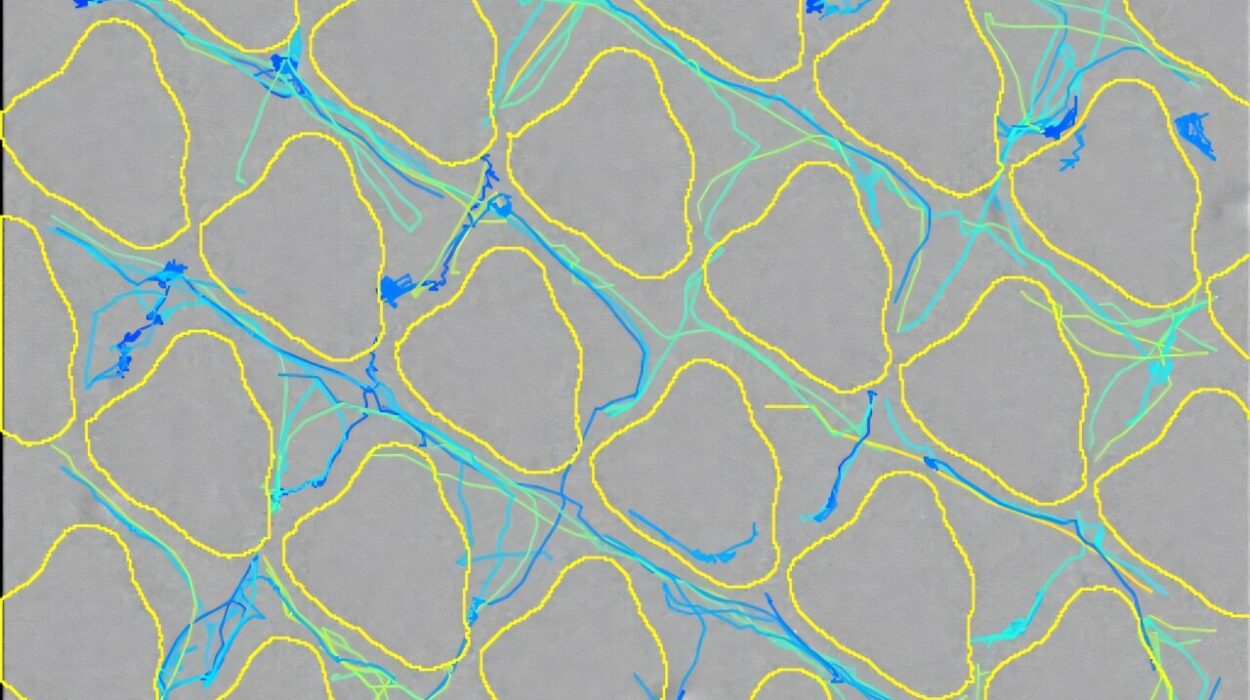

Footprints are not just impressions in the soil. They are moments, frozen. Unlike bones or tools, footprints capture movement. They show us how our ancestors walked, whether they slipped, how fast they moved, whether they carried burdens. Some even show interactions—tracks converging, diverging, a story unfolding across a prehistoric surface. These ancient impressions are the closest we have to watching someone move through time. And among them, the oldest known human footprints give us a profound and poetic glimpse into the dawn of our species.

But where exactly are these footprints found? Who made them? And what secrets do they still hold?

When Feet Become Fossils

For a footprint to fossilize, the conditions must be extraordinary. The ground must be soft enough to record detail but firm enough to hold shape. Soon after the print is made, it must be rapidly covered—perhaps by ash from a volcanic eruption, a flood-borne layer of silt, or drifting sand. Over time, these layers harden into rock. The result is rare, but when it happens, it captures a direct record of life in motion.

Footprints are known as trace fossils, or ichnofossils—they are not parts of the organism, like bones or teeth, but traces of its activity. Unlike artifacts shaped by intelligent hands, footprints are made unintentionally. They offer raw, unfiltered truth. And unlike genetic evidence, which tells us who someone was, footprints tell us what someone did.

In recent decades, paleontologists, archaeologists, and geologists have uncovered a growing number of ancient human footprints across the globe. Each one has rewritten a piece of our shared story. But none are as haunting, nor as illuminating, as the oldest of them all.

Laetoli, Tanzania: The Dawn Walkers

In the late 1970s, paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey and her team were excavating in northern Tanzania, near the volcanic site of Laetoli. It was a region already rich in fossils, but no one expected what came next. After a series of rare rains, local workers noticed what appeared to be animal tracks hardened into ancient volcanic ash. Upon further inspection, Leakey realized they weren’t just animal tracks—they included something else. Something eerily familiar.

There, stretching over 70 feet, were the unmistakable imprints of upright bipedal walking—three early humans, side by side, walking across the ash like ghosts from deep time.

The ash layer was dated to approximately 3.66 million years ago. The footprints belonged to an early hominin species known as Australopithecus afarensis—the same species as the famous fossil “Lucy.” These weren’t modern humans, but they were our ancestors—or close cousins.

The Laetoli footprints were astonishing not just for their age, but for their clarity. You could see arches, toe placement, stride length. They showed that bipedal walking—so central to what makes us human—was already well developed at this early stage. This was not a creature clumsily experimenting with uprightness. It was someone confidently walking, perhaps chatting, perhaps looking at the sky—just like us.

And then there was the intimacy of it. One of the tracks appeared smaller, walking close beside the larger ones. A child? A mate? There was even evidence that one individual occasionally turned to look behind. It was easy—perhaps too easy—to imagine a little family walking together through volcanic ash, oblivious to the immortality they were about to achieve.

White Sands, New Mexico: A New Chapter

For decades, Laetoli held the title of the oldest known hominin footprints. But in 2021, a new discovery stunned the scientific world—and pushed back the timeline of human presence in the Americas.

At White Sands National Park in New Mexico, archaeologists discovered a series of human footprints preserved in ancient lakebed sediments. Some of the prints were deep, indicating someone was carrying a load—perhaps a child. Others showed careful, zigzagging paths—possibly to avoid hazards or puddles. But it wasn’t the behavior that made headlines. It was the date.

Using radiocarbon dating of seeds embedded in the sediment layers, researchers determined the footprints were between 21,000 and 23,000 years old—thousands of years older than the previously accepted timeline for humans in North America.

This forced a dramatic reassessment of human migration. Previously, most scholars believed humans arrived in the Americas around 13,000 years ago, crossing a land bridge from Siberia and moving southward after glaciers receded. But the White Sands footprints suggest a much earlier presence—during the peak of the last Ice Age, when massive ice sheets would have made travel nearly impossible.

The implications are profound. Either humans arrived far earlier than we thought—or they found unknown ways to cross forbidding terrain. It also opens the door to lost cultures—entire chapters of prehistory waiting to be unearthed.

But beyond the geopolitics of migration, the White Sands footprints are quietly poetic. One trail shows someone walking for miles, possibly carrying a child, then returning alone. Was the child dropped off? Was it a mother? A father? We don’t know. But the prints are deeply human in every sense. They remind us that love, duty, fatigue, and care are ancient emotions—older than language, older than memory.

Fossil Footprints from Other Corners of the Earth

Though Laetoli and White Sands are the most famous, they are not alone. Around the world, ancient human footprints are turning up in surprising places, each one adding depth and texture to our story.

In Ileret, Kenya, scientists have found Homo erectus footprints dating to around 1.5 million years ago. Unlike Australopithecus, Homo erectus had a modern body shape. These tracks are remarkably similar to ours—same arch, same gait. They confirm that Homo erectus was an efficient, long-distance walker. These people may have hunted in groups, coordinated travel, and communicated using primitive language. Their footprints hint at social complexity.

In South Africa, more than 100,000-year-old human footprints have been found in beach sands—some of the earliest evidence of Homo sapiens. One set at Langebaan Lagoon includes the print of a child, estimated to be about nine years old. Another trail seems to show people walking together, perhaps along a shoreline, looking for shellfish or companionship.

And in Italy, in the Roccamonfina volcano region, ancient human ancestors—perhaps Homo heidelbergensis—left tracks in volcanic ash nearly 350,000 years ago. The locals once called them “the Devil’s Trails,” believing only something supernatural could have left such haunting traces in stone. In a way, they were right—these were humans of a kind now extinct, speaking to us from a time before history.

What Can Ancient Footprints Really Tell Us?

You might wonder: what can a footprint reveal, besides a foot?

As it turns out, quite a lot. Footprints can be measured for depth, spacing, and orientation. From this data, scientists can estimate the individual’s height, weight, speed, and gait. Was the person walking or running? Did they carry anything? Were they limping? Did others walk with them? These questions can often be answered with surprising precision.

Moreover, footprints offer something fossils often can’t: context. They show us how many individuals were present at once, how they moved in relation to each other, and what the environment was like. In some cases, you can even see animal tracks crossing human paths, suggesting interactions—or perhaps shared watering holes.

And footprints stir the imagination in ways bones and stones rarely do. A femur is anatomy. A footprint is a heartbeat.

Tracing the Evolution of Movement

Human bipedalism—our signature way of moving—didn’t appear suddenly. It evolved gradually, through countless generations of half-walkers, half-climbers. Ancient footprints let us trace that transformation not in theory, but in practice.

The Laetoli prints suggest that Australopithecus afarensis walked upright, with a gait not unlike ours. But later footprints, like those from Ileret or South Africa, show more refined motion—longer strides, better balance. They document the evolution of efficient walking, and perhaps even running. Some experts argue that endurance running helped early humans hunt—following animals until they collapsed from exhaustion.

That ability, encoded in the curves of our feet and the swing of our hips, is visible in those early trails. In their silent tracks, we see the emergence of the human form—muscle, motion, momentum.

The Emotional Weight of Ancient Steps

Why do we feel such connection to footprints? Why do they strike us as so personal?

Perhaps it’s because footprints speak in a language everyone understands. You don’t need to be a scientist to recognize a footprint. It’s a symbol of presence—someone was here. They stood where you now stand. They walked the earth you now walk. The distance of time collapses.

Footprints are inherently vulnerable. They are the marks of bare skin on earth, a physical touch across eons. They suggest not only movement, but intent. To leave a footprint is to have gone somewhere—to have chosen a direction.

They also raise haunting questions. What happened to the people who made them? Did they survive? What did they see? Did they know, even dimly, that the earth would remember them?

Preserving the Past in a Fragile Present

Many ancient footprints are now endangered. Coastal erosion, construction, climate change, and even tourism threaten these fragile relics. At White Sands, the ancient lakebed is drying out and cracking. In Laetoli, early restoration efforts actually obscured some of the tracks.

Efforts are now underway globally to preserve, 3D-scan, and digitally archive these sites. But nothing matches the visceral impact of seeing them in person—of standing beside a footprint older than any nation, any language, any memory.

It reminds us that we, too, are just visitors here, leaving tracks that may or may not endure.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Trail

The oldest human footprints do more than expand our knowledge—they awaken something within us. They stir empathy for the unknown, admiration for the journey, and reverence for time. In a world obsessed with the new, they are an invitation to remember the ancient.

Every footprint is a story. Some are short—a single print, a moment of contact. Others stretch for hundreds of feet, a journey traced across landscapes now lost. But all of them whisper the same truth: we were here. We walked. We mattered.

We do not know their names. We cannot ask them questions. But thanks to mud, ash, and time, we can follow them—step by step—into the heart of who we are.