To hold a fossil in your hand is to clasp a message from a world long vanished. Whether it’s a fragment of bone, a coiled ammonite, or the delicate impression of a fern, a fossil tells the story of life that lived millions of years ago. But for every fossil unearthed, countless others are lost forever, their stories swallowed by time and earth. Why are fossils so rare?

This question reveals a deeper truth—not only about paleontology, but about the nature of preservation, the cruelty of time, and the sheer luck required for even a sliver of the past to survive into the present. Fossils are not simply the remnants of prehistoric life. They are miraculous accidents. They are survivors of a brutal and relentless march toward decay and erasure.

To understand the rarity of fossils is to understand the fragility of memory—how even the hardest bone is no match for the geologic forces of erosion, heat, and pressure. It is to understand that nature forgets far more than it remembers.

The Brief and Brutal Journey From Life to Fossil

Most living things never become fossils. In fact, the vast majority of organisms vanish without a trace. Their bodies are scavenged, decayed, dissolved, or obliterated by geological processes. Fossilization is not the rule—it’s the exception.

When an organism dies, its soft tissues—skin, muscles, organs—are the first to go. Bacteria, fungi, and scavengers descend almost immediately. Insects swarm, bones are scattered, and within days or weeks, most of the biological matter has been consumed or degraded. Even the hardest parts—bones, teeth, shells—rarely last more than a few years unless quickly buried.

For fossilization to even have a chance, an extraordinary series of conditions must be met. First, the organism must escape destruction long enough to be buried. This alone is a rare event. Think of the thousands of wildebeest that die during annual migrations. How many are quickly buried in silt before scavengers find them? Almost none.

Next, the burial environment must be favorable. The best places for fossilization are areas with rapid sediment deposition—river deltas, floodplains, lakebeds, and seafloors. These environments cover remains in fine particles that protect them from oxygen, microbes, and weathering.

But even burial is not enough. Over the next thousands or millions of years, the remains must undergo chemical transformation. Groundwater rich in minerals seeps through the sediment, gradually replacing the original material with more stable compounds like silica or calcite. This process, called permineralization, can preserve microscopic details—but it is not guaranteed.

Throughout this entire ordeal, geological forces are working against preservation. Tectonic uplift, erosion, volcanic activity, and metamorphism can obliterate fossils long before they’re discovered. Only a tiny fraction survive—and an even tinier fraction are ever exposed at the surface where humans might find them.

The Math of Vanishing Worlds

Scientists estimate that more than 99% of all species that have ever lived on Earth are now extinct. That’s billions—perhaps trillions—of species across Earth’s 4.5 billion-year history. And yet, the total number of known fossil species is measured in the hundreds of thousands. The fossil record is vast in time but narrow in scope. It is a broken mirror, reflecting only pieces of what once was.

This scarcity isn’t just due to bad luck—it’s also due to bias. Not all organisms have the same chance of becoming fossils. Creatures with hard parts—bones, shells, exoskeletons—are vastly more likely to fossilize than soft-bodied animals. That’s why we have an abundance of trilobite shells but almost no evidence of their soft internal organs. It’s why we know the bones of dinosaurs but not their hearts, their tongues, or their voices.

Likewise, animals that lived in or near water have a much higher chance of preservation. Terrestrial creatures are less likely to be buried quickly, and their remains are more likely to be scattered. The fossil record is thus skewed toward marine environments.

Even size plays a role. Large animals are less likely to be buried intact. Their bodies take longer to decompose, attracting scavengers and weathering. Tiny creatures, on the other hand, might be too delicate to survive sediment pressure. So, paradoxically, both giants and microbes face barriers to fossilization, albeit for different reasons.

Time Destroys More Than It Preserves

Imagine a world teeming with life—ferns towering over dragonflies the size of hawks, amphibians the size of crocodiles, and strange fish-like creatures flopping between pools. Now imagine that world being wiped away not by a cataclysm, but by time itself. So much of Earth’s past is missing, not because it never existed, but because it wasn’t preserved.

The geologic record is full of gaps—times when no new sediments were deposited, or when existing layers were eroded away. These gaps, called unconformities, can span millions of years. It’s like trying to reconstruct a library’s history from a handful of charred pages.

Even rocks that do preserve fossils are not immune to change. Over time, sediments become buried deeper under additional layers. Pressure increases. Temperature rises. Minerals begin to change. At a certain point, the rocks metamorphose, and any fossils they contain are destroyed. Mountains rise and fall. Continents drift. Oceans close. Fossils are buried, crushed, melted, or carried out to sea.

This relentless recycling of the Earth’s crust means that entire chapters of life’s history are gone forever. We will never know the full story. We will never see the countless creatures that lived and died unnoticed. The fossil record is not just rare—it is haunted by absence.

The Fossils We Do Find

Despite the odds, fossils do survive—and when they do, they become time capsules. A single fossil can revolutionize our understanding of evolution, extinction, climate, and ecology.

When paleontologists discovered Tiktaalik in the Canadian Arctic, they found a transitional form between fish and land animals. Its fin-like limbs and flattened skull offered a snapshot of life in the act of changing. When the feathered dinosaur Archaeopteryx was discovered in Germany in the 19th century, it confirmed Darwin’s prediction that birds descended from reptiles. When the Laetoli footprints in Tanzania were unearthed, they showed bipedal hominins walking across volcanic ash nearly four million years ago.

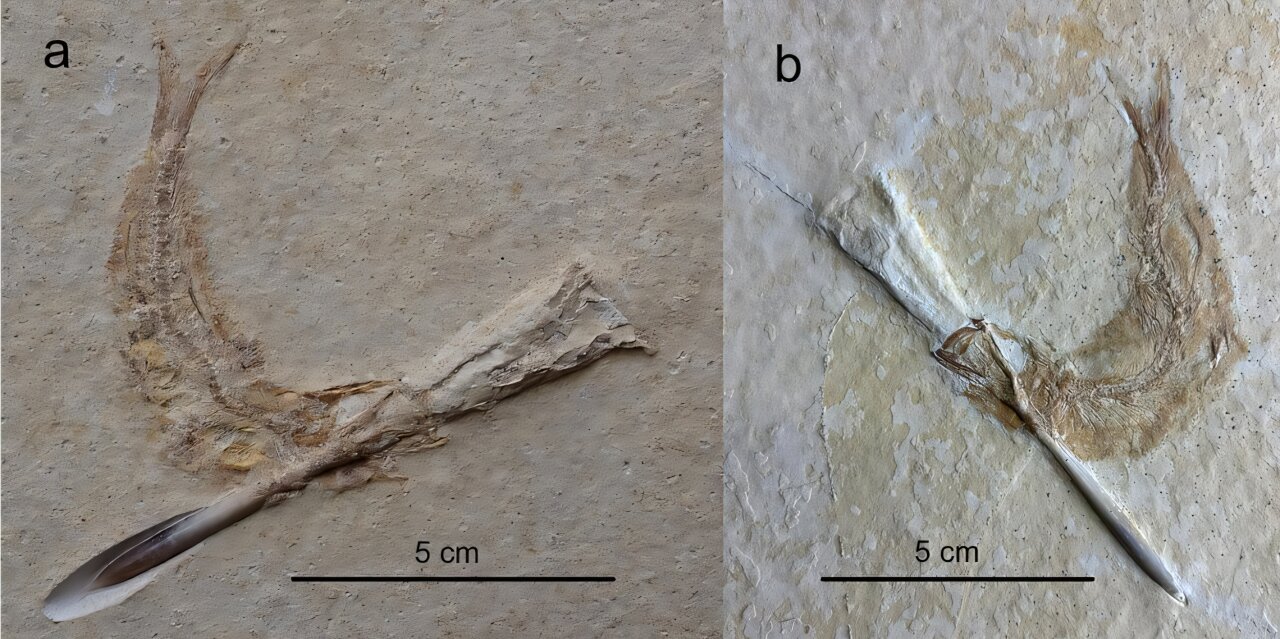

And then there are the fossils trapped in amber—tiny insects, lizards, even feathers, perfectly preserved as if frozen in time. They are among the most exquisite fossils ever found, showing details down to the microscopic hairs on a fly’s wing.

Each of these discoveries is a miracle. Each one required the perfect alignment of biology, geology, and luck. They are rare because they must be.

Fossilization’s Many Forms

While permineralization is the most familiar form of fossilization, it is not the only one. Sometimes, fossils form through carbonization—a process in which only the carbon-rich film of an organism remains, often seen in fossil plants or delicate animals like jellyfish. Sometimes, organisms leave behind molds or casts—empty impressions in the rock that preserve their shape even when the original material is gone.

In rare conditions, soft tissues may be preserved by freezing, desiccation, or chemical processes. Woolly mammoths have been recovered from Siberian permafrost with flesh and fur intact. Bog bodies in northern Europe—human remains thousands of years old—have been preserved by tannic acids in peat. These are not technically fossils in the mineralized sense, but they represent the same phenomenon: the unexpected defiance of decay.

Then there are trace fossils: footprints, burrows, coprolites (fossilized feces), and even nests. These don’t preserve the body of the organism but offer glimpses of behavior. They are among the most intimate fossils we have—showing not just what an organism was, but what it did.

The Human Bias in the Search for Fossils

Even among the fossils that survive, discovery is a matter of geography and chance. We only find fossils where sedimentary rocks are exposed at the surface. Deserts, badlands, road cuts, and quarries are prime locations. Tropical rainforests, where thick vegetation and acidic soils destroy bones rapidly, are poor environments for fossil preservation—and even worse for fossil discovery.

Human exploration is biased, too. Fossil-hunting expeditions are expensive and often focus on regions that are politically stable, accessible, and already known to be fossil-rich. As a result, much of the world’s deep-time history remains unexplored. We don’t know what we’re missing.

Moreover, many fossil sites are lost to development, looting, or natural erosion before scientists ever see them. Some fossils are accidentally destroyed during construction. Others are sold on the black market, lost to private collections. The world’s fossil heritage is fragile—not just geologically, but culturally.

What Fossils Can’t Tell Us

For all they reveal, fossils are incomplete. They don’t preserve behavior, intelligence, or color—at least not easily. We don’t know what sounds dinosaurs made. We don’t know how ancient reptiles courted or how prehistoric insects navigated. Fossils rarely preserve organs, especially brains. And even the best-preserved skeleton tells us nothing of the animal’s consciousness, its social life, or its fears.

Some recent advances—like pigment detection in fossil feathers or CT scans of brain cavities—have begun to crack these mysteries. But the truth remains: fossils are echoes, not recordings. They tell us what life was, but only partially. They are shadows on the cave wall, not the light.

Why the Rarity of Fossils Matters

Understanding the rarity of fossils doesn’t diminish their value—it magnifies it. Every fossil is a survivor, a whisper of what once lived and breathed in worlds unlike our own. The scarcity reminds us of how much we’ve lost and how precious the fragments that remain truly are.

Fossils are not just tools of science; they are vessels of wonder. They allow us to peer into deep time, to see the Earth not as a static stage but as an evolving organism. They remind us that we, too, are part of this grand lineage—that we walk on ground once trod by trilobites and titanosaurs, by armored fish and primitive apes.

They remind us, too, of our responsibility. To preserve fossil sites, to fund research, to resist the commodification of ancient remains. Fossils belong not to individuals, but to the story of life. To all of us.

The Incomplete Record Is Still a Story

Even a broken fossil can tell us something. A single tooth can reveal diet, habitat, lineage. A fragment of bone can hint at locomotion, age, or evolutionary relationships. The incomplete record is still a record—and when assembled across continents and centuries, it becomes a chorus of lost voices.

Paleontology is, in many ways, an act of resurrection. Not of bodies, but of knowledge. It’s the art of coaxing meaning from stone. And in the end, the rarity of fossils is not a barrier—it’s a testament to persistence, both of the fossils themselves and of the scientists who seek them.

In every cracked vertebra, in every ripple-marked rock, in every spiral shell embedded in a cliff face, there is a truth older than history and grander than legend: Life existed before us. It changed, it adapted, it flourished—and it left behind traces for those willing to look.

The Sacred Fragility of Deep Time

So why are fossils so rare? Because life is ephemeral. Because death is noisy and messy and fast. Because time is a devourer. Because geology is merciless. Because the Earth is not a museum but a living, shifting body that forgets its past.

But that rarity is what makes fossils sacred. They are not common curiosities. They are gifts. They are time travelers in stone. They are the evidence that Earth has lived many lives—and will live many more.

And perhaps, one day, when our species has vanished into the same cycle of dust and sediment, something will be left behind. A footprint. A tool. A fragment of bone. And another intelligence, in another age, might discover it and wonder who we were. And in that moment, the chain will continue—one rare fossil at a time.