Before there were cities, before there were humans, before flowers even bloomed on the first tree—there were dinosaurs. They roamed a planet unfamiliar to our modern eyes. A place of steaming jungles and sun-baked deserts, where volcanic mountains belched fire and shallow seas washed over continents. This was Earth in the Mesozoic Era, and for more than 160 million years—an almost incomprehensible stretch of time—dinosaurs were its undisputed rulers.

They were not just giant lizards as once thought. They were dreamlike, alien, and astonishingly diverse. Some were the size of pigeons, darting between ferns. Others towered above the forest canopy, heavier than twenty elephants. They had feathers, horns, sails, beaks, claws, and even armor plates. But what truly made them remarkable was not their size or their strength—it was their ability to adapt. Dinosaurs were more than just survivors; they were shape-shifters in the grand theatre of evolution, constantly innovating to meet the challenges of an ever-changing world.

So how did they do it? How did these ancient creatures not only survive, but thrive across millennia in a volatile, often dangerous world? The answer lies in a story of biology, climate, geography—and astonishing evolutionary resilience.

A World in Flux: The Mesozoic Landscape

The age of dinosaurs—also known as the Mesozoic Era—is divided into three periods: the Triassic, the Jurassic, and the Cretaceous. This stretch of time, from about 252 to 66 million years ago, saw Earth undergo dramatic transformations. Supercontinents split apart. Sea levels rose and fell. Volcanoes reshaped the landscape. Atmospheres warmed and cooled.

When dinosaurs first appeared during the late Triassic, the world was a single massive landmass known as Pangaea. This supercontinent created harsh, desert-like interiors due to its vast size and lack of coastal moderation. Dinosaurs arose not in gentle conditions, but in a crucible of drought, volcanic eruptions, and fierce competition.

But they didn’t just scrape by—they flourished. As Pangaea slowly broke into pieces and formed the continents we know today, dinosaurs radiated into new ecological niches. Evolution played a long game with them, testing their forms and functions against a background of shifting climates and growing biodiversity.

One of their greatest advantages was time. The age of dinosaurs spanned more than 160 million years. By comparison, humans have been around for just about 300,000 years. Dinosaurs had thousands of millennia to evolve, adapt, and diversify into nearly every possible shape life could take on land.

The Secret of Their Skeletons

At the heart of the dinosaur story lies a miracle of engineering: their bones. Dinosaur skeletons weren’t just big—they were brilliantly constructed.

Many dinosaurs had hollow bones, which made their skeletons lighter without sacrificing strength. This was especially important for theropods—the bipedal, often predatory dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex or Velociraptor. Their lightweight structure allowed for greater agility and, in many species, eventually enabled the evolution of flight.

The arrangement of their hips and legs was another key innovation. Unlike reptiles that sprawl to the sides, dinosaurs had legs positioned directly beneath their bodies. This vertical limb posture allowed for more efficient movement and endurance. It’s no coincidence that mammals—and later, birds—would also adopt this configuration.

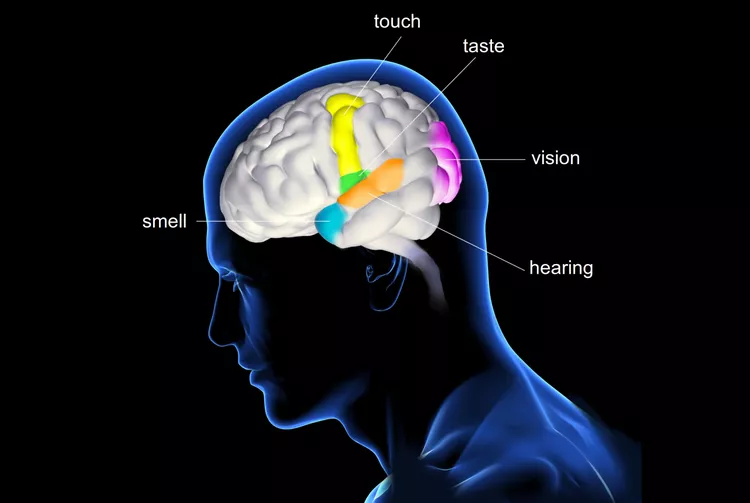

Moreover, their skulls were often designed with specialized features: crests for visual signaling, beaks for cropping plants, nasal passages for trumpeting calls, and labyrinthine sinuses that helped lighten the head or regulate temperature. Their diversity of adaptations gave dinosaurs a competitive edge in virtually every environment.

Cold-Blooded or Warm-Blooded?

For much of the 20th century, dinosaurs were imagined as sluggish, cold-blooded reptiles—oversized crocodiles lumbering through prehistoric swamps. But a scientific revolution in the 1970s began to change everything.

New fossil evidence, particularly from the fine-grained rocks of China and North America, revealed not only dinosaur footprints and skin impressions, but entire bodies draped in feathers. It became clear that many dinosaurs, especially the theropods, were warm-blooded—or at least had metabolic systems far more active than modern reptiles.

Warm-bloodedness (endothermy) allowed them to maintain internal temperatures and remain active in colder environments. This, in turn, opened up new possibilities: longer hunting periods, faster movements, more parental care, and wider geographic ranges.

Even massive herbivores like sauropods may have had metabolic rates higher than previously thought. Their massive size would have created a sort of thermal inertia—retaining heat like a giant furnace, allowing for steady, regulated body temperatures.

In short, dinosaurs weren’t cold-blooded monsters. They were active, alert, and in many cases, astonishingly bird-like.

The Rise of the Giants

One of the most visually stunning aspects of dinosaurs was their sheer size. No land animals before or since have matched the enormity of creatures like Argentinosaurus or Patagotitan—sauropods that stretched over 100 feet and weighed up to 70 tons.

How did dinosaurs grow so large?

Several evolutionary advantages enabled their growth. First, their efficient respiratory systems—including bird-like air sacs—allowed for high oxygen intake and helped cool their massive bodies. Second, their reproductive strategies—laying large numbers of eggs—helped offset the risks of high juvenile mortality.

Additionally, they lived in a world with rich vegetation, especially during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. With no large mammalian competitors, herbivorous dinosaurs had access to plentiful food sources and little pressure to stay small. Predators, in turn, had to grow large enough to take down these enormous prey.

Interestingly, their growth patterns were different from ours. Dinosaurs often grew quickly and continued growing throughout much of their lives, unlike mammals, which generally reach a fixed adult size.

Survival Through Specialization

Not all dinosaurs were giants, though. Many were the size of dogs, chickens, or even squirrels. The key to their survival wasn’t always size—it was specialization.

In every ecosystem, dinosaurs adapted to specific roles. Small theropods evolved sharp vision and claws for hunting insects and small vertebrates. Duck-billed hadrosaurs developed intricate dental batteries capable of grinding tough plant material. Armored ankylosaurs evolved clubbed tails and bony plates to ward off predators. And horned ceratopsians like Triceratops likely used their dramatic frills and horns for both defense and social display.

The diversity of form reflects a powerful evolutionary principle: adaptability through specialization. Each new niche—whether in the treetops, plains, or riverbanks—was a fresh canvas for dinosaur innovation.

This specialization also points to complex ecosystems. Dinosaurs were not isolated monsters. They lived in dynamic environments with forests, rivers, and weather patterns. They interacted with early mammals, flying reptiles, marine reptiles, amphibians, and countless insects. Their lives were part of rich and often delicate webs of ecological interaction.

Parenthood and the First Nests

One of the most touching revelations in recent paleontology is that many dinosaurs were attentive parents. Fossilized nests, eggs, and even embryos provide rare windows into their reproductive lives.

Species like Maiasaura—whose name means “good mother lizard”—built large nesting colonies where adults would care for their young. Fossils show evidence of juveniles staying in nests for extended periods, suggesting feeding and protection by adults.

Some theropods were found fossilized in brooding positions, much like modern birds, sitting atop eggs to regulate their temperature. The discovery of embryos with developing feathers inside the shells only deepens the connection between dinosaurs and birds.

These behaviors indicate that dinosaurs weren’t just instinct-driven beasts. Many had complex social structures, communication methods, and parental investment. These traits not only enhanced offspring survival, but also laid the foundation for avian behavior millions of years later.

Wings in Waiting: The Dawn of Flight

One of the most astonishing chapters in dinosaur history is their transformation into birds. This isn’t a metaphor or a poetic comparison—it’s evolutionary fact. Birds are living dinosaurs, direct descendants of small, feathered theropods.

Feathers, once believed to be unique to birds, are now known to have appeared in a variety of non-avian dinosaurs. Initially, feathers may have evolved for insulation or display. Over time, they became more complex, giving rise to gliding and, eventually, powered flight.

Species like Archaeopteryx, discovered in 1861, show transitional features: teeth in beaked jaws, clawed wings, long bony tails, and fully developed flight feathers. Later fossils revealed an even broader spectrum of winged dinosaurs, including Microraptor—a four-winged glider—and Anchiornis, whose plumage could rival any bird today.

Flight was not just a clever trick. It was a survival strategy. It opened the sky as a new frontier, provided escape from predators, and allowed rapid colonization of diverse environments.

Even after the great extinction event that ended most dinosaur lineages, birds carried the torch of their ancestors into the modern age.

The Fall of the Giants

No story of the dinosaurs is complete without their sudden and catastrophic downfall.

Around 66 million years ago, a massive asteroid struck the Earth near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The impact unleashed apocalyptic conditions: shockwaves, wildfires, global darkness, acid rain, and a “nuclear winter” that lasted for months or even years.

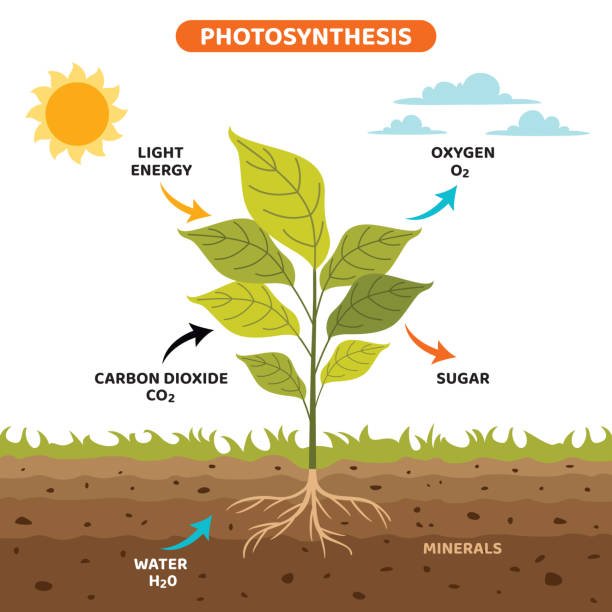

Photosynthesis halted. Food chains collapsed. The lush Cretaceous world quickly transformed into a wasteland.

In that darkness, about 75% of all species on Earth vanished. Among the casualties were the non-avian dinosaurs. But some small, feathered descendants survived. The birds, with their ability to fly, their diverse diets, and rapid reproductive cycles, managed to make it through the chaos.

It wasn’t weakness that doomed the dinosaurs—it was bad luck. A cosmic accident erased a magnificent lineage in the prime of its reign.

Dinosaurs in the Mirror

And yet, the dinosaur story never really ended. Every time you hear the song of a bird or watch a hawk glide overhead, you are witnessing the legacy of the Mesozoic. Dinosaurs have not vanished; they’ve adapted, once again, to a changing world.

We now understand that dinosaurs were not evolutionary dead ends. They were some of the most successful animals to ever walk the Earth. Their reign lasted fifty times longer than the entirety of human civilization. Their adaptability—from desert-dwellers to swamp-stalkers to airborne acrobats—was the true source of their power.

They weren’t just beasts—they were beings. Living things that hatched from eggs, hunted in packs, cared for their young, and looked up at volcanic skies just as we look up at stars.

Epilogue: Lessons from a Lost World

What can we, fragile newcomers in the cosmic timeline, learn from the lives of dinosaurs?

First, we are reminded that dominance is never permanent. Even the mightiest empires—built not of stone, but of flesh and bone—can fall in the face of catastrophe. The planet is indifferent to power; only adaptability matters.

Second, we learn that survival is a story of innovation. From warm-blooded metabolism to feathered flight, dinosaurs remind us that nature rewards creativity, not conformity.

Finally, their bones teach us humility. They echo across eons, reminding us that Earth’s history is not our own. We are guests in a home they once ruled, inheritors of a world shaped in part by their long-forgotten footsteps.

And perhaps, in those moments when a crow calls or a sparrow flits past your window, you might hear a whisper from that ancient world—a reminder that the dinosaurs have never really left us.