Archaeology often reveals fragments of forgotten lives—pottery, bones, weapons—that help us reconstruct the distant past. But every so often, something far more delicate and unexpected emerges, reminding us of the depth of human imagination and symbolism. Such is the case with a recent discovery in Domasław, Poland, where Dr. Agata Hałuszko and her team uncovered a remarkable burial dating back nearly 3,000 years.

In a cremation grave belonging to the Lusatian Urnfield culture, researchers identified an extraordinary ornament crafted from beetles. This fragile artifact, preserved by chance and circumstance, provides a rare glimpse into the ritual, emotional, and symbolic lives of people living in the Hallstatt period, between roughly 850 and 400 BC.

Grave 543 and Its Child Occupant

The grave in question, known as Grave 543, was part of a vast Lusatian cemetery containing over 800 cremation burials. Unlike inhumation burials, where skeletal remains can tell us much about the dead, cremation graves often yield fewer personal details. Yet here, the story unfolded in surprising richness.

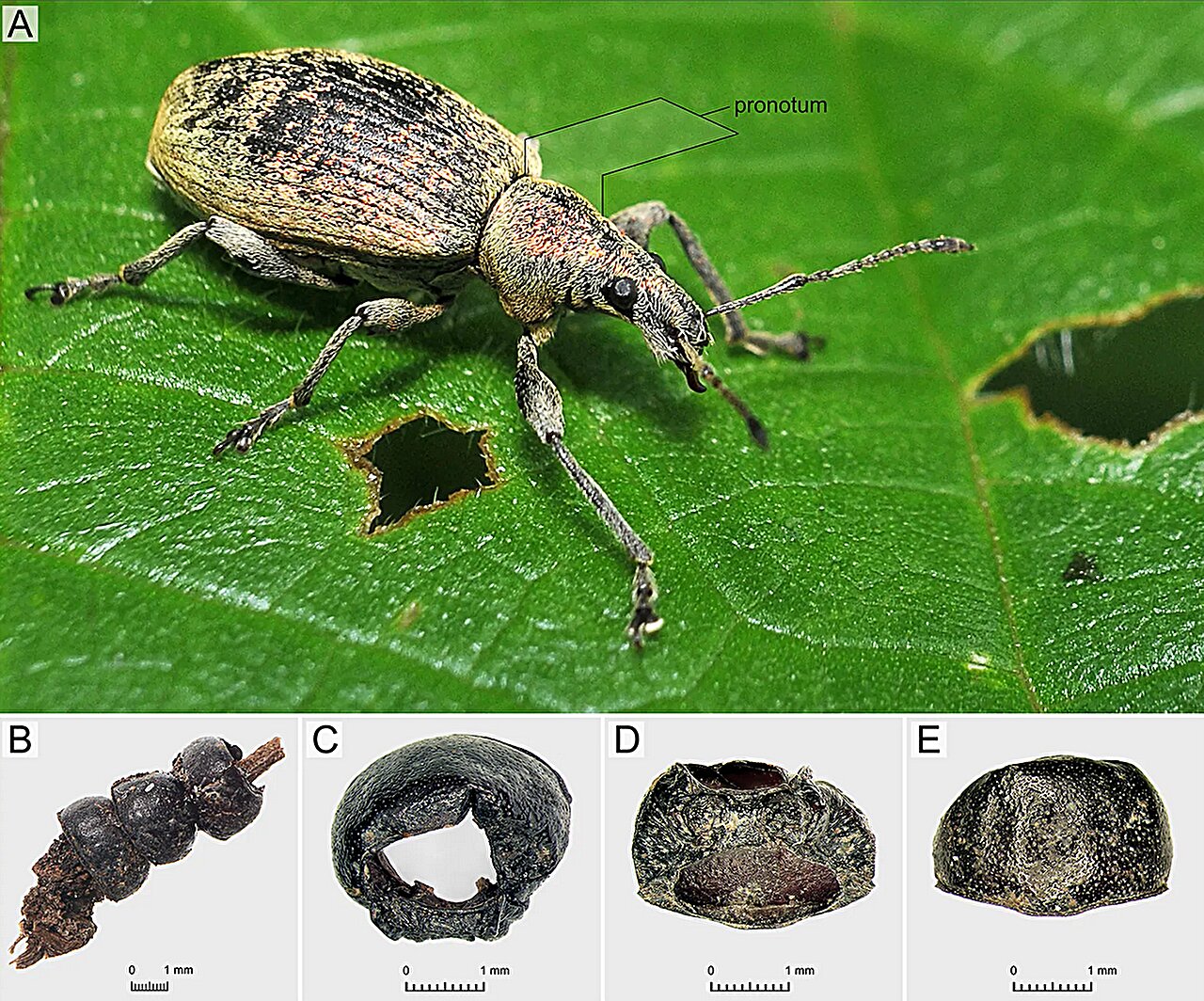

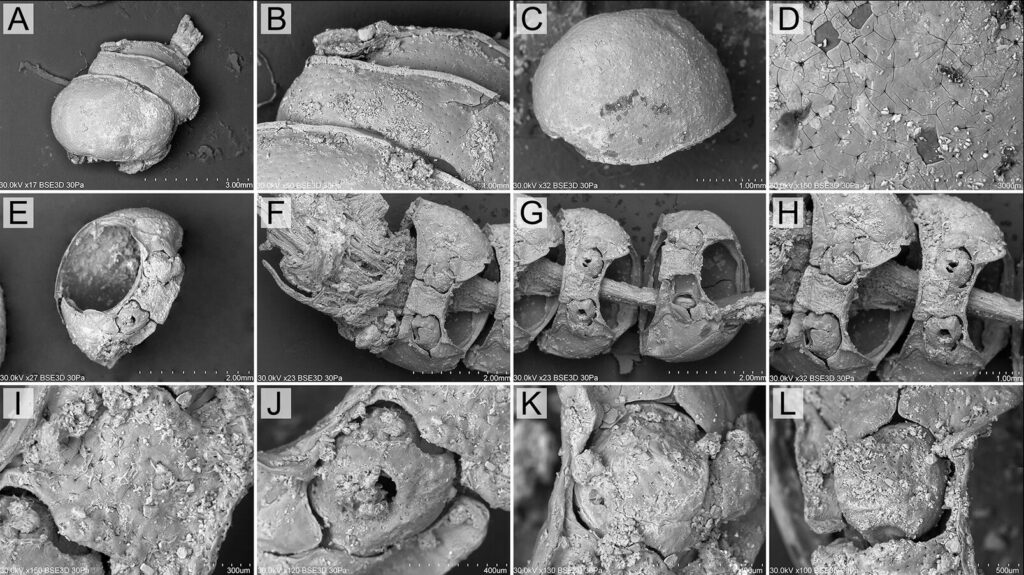

Urn 1 of Grave 543 contained the cremated remains of a child no older than 9 or 10 years old. Alongside the ashes were fragments of goat or sheep bones—perhaps offerings of food for the afterlife—as well as a bronze harp-shaped fibula, a braid, pieces of birch bark, and even microscopic pollen from dandelions, suggesting a seasonal connection. Among these objects were 17 tiny exoskeleton fragments belonging to a single species of beetle: Phyllobius viridicollis.

The Beetles and the Seasons of Burial

The choice of beetle was not incidental. Phyllobius viridicollis is a weevil species that appears in the natural world only from May to July. Their seasonal presence provided archaeologists with an important clue: the burial must have taken place during late spring or early summer.

This small detail transforms our understanding of the ritual. The act of burial was not a random event but one carefully timed, perhaps aligning with natural cycles of growth, fertility, or renewal. For the Lusatian people, who lived closely with the rhythms of the land, such timing could have carried deep symbolic weight.

The Making of a Fragile Ornament

Perhaps most astonishing is that the beetle fragments were not scattered randomly. Careful study revealed that their heads, legs, and abdomens had been deliberately removed, leaving behind the shimmering greenish wing cases. Some of these were even threaded onto a blade of grass, creating what can only be described as a necklace or decorative ornament.

The delicacy of this creation cannot be overstated. Insects are among the most perishable organic materials, rarely surviving for millennia. Their preservation here was possible only because of the presence of bronze. As Dr. Hałuszko explains, when bronze corrodes, the resulting green patina impregnates nearby organic matter, protecting it from decay. In this way, the fragile beetle shells, blades of grass, and even traces of birch bark endured for centuries beneath the earth.

Why Beetles? Symbolism and Parallels

The reason for including beetle ornaments in a child’s grave is open to interpretation. Were they decorative, symbolic, or protective? The answer may be a combination of all three.

Ethnographic accounts from the Hutsuls, a Slavic group from the Carpathian region, describe necklaces made from rose and copper chafers. These ornaments, often worn by young girls, were believed to carry protective qualities or even bring prosperity. Beetle jewelry also appeared in entirely different cultural contexts, such as Victorian England, where live beetles adorned with gold chains were worn as exotic fashion statements.

These cross-cultural parallels suggest that beetles have long held symbolic significance, representing beauty, transformation, or protection. In the case of Grave 543, it is possible that the ornament was created specifically for the burial, rather than being a cherished personal item. Its fragility makes it unlikely that it was worn extensively in life. Instead, the beetles may have been chosen deliberately to accompany the child into death, carrying symbolic meaning we can only begin to guess.

Ritual, Memory, and Meaning

The inclusion of beetles in the child’s urn is more than a curiosity—it is a testament to how deeply the Lusatian people invested in the symbolism of their burials. The beetle necklace, ephemeral by nature, underscores the fleetingness of life itself. By placing such fragile objects in the urn, mourners may have been expressing both grief and hope: grief for a life cut short, and hope for transformation in another world.

The presence of birch bark, goat bones, and pollen alongside the ornament further supports this interpretation. Each element seems to have carried ritual significance, combining to form a burial rich in symbolic gestures. The child was not merely laid to rest but surrounded with objects carefully chosen to bridge the boundary between the living and the dead.

A Rare Glimpse into Lost Traditions

Discoveries like this are exceedingly rare in archaeology. Organic materials, especially those as delicate as insect exoskeletons, almost never survive. Without the fortunate preservation enabled by bronze corrosion, this story would have been lost forever. The beetle ornament, therefore, is more than an artifact—it is a rare and precious testimony to the creativity and spirituality of an ancient culture.

Through this discovery, we learn that the Lusatian people did not see insects as trivial or meaningless. Instead, they recognized beauty and symbolism in creatures that today might be overlooked. They transformed beetles into art, and art into ritual, embedding meaning into even the smallest forms of life.

The Echo of an Ancient Gesture

When we gaze at the beetle ornament from Grave 543, we are witnessing a human gesture preserved across 2,500 years: the act of mourning, of remembering, of honoring the dead. The fragile shells remind us that the people of the Lusatian culture were not so different from us. They loved, they grieved, they sought meaning in nature, and they used ritual to give shape to loss.

This discovery is not just about beetles, but about humanity. It is a reminder that even in the deep past, people found ways to express beauty and hope in the face of death. And in that fragile ornament, strung together on a blade of grass, we glimpse the universality of human experience—our enduring desire to create meaning in the moments when words are not enough.

More information: Agata Hałuszko et al, Beetle body parts as a funerary element in a cremation grave from the Hallstatt cemetery in Domasław, south-west Poland, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.10182