In the heart of Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park—a landscape long celebrated for its rich tapestry of fossilized bones—a discovery has emerged that offers something bones alone cannot provide: motion, behavior, and a glimpse of prehistoric interaction frozen in time. A newly uncovered tracksite, nestled within the sunbaked ridges of this Canadian badland, has revealed something extraordinary—footprints from several different species of dinosaurs, all walking together, side by side.

These 76-million-year-old impressions, carefully unearthed during an international field course in July 2024, tell a story no skeleton ever could. They suggest that some dinosaurs may have lived not only within their own kind but also alongside others—an interspecies herd moving across ancient floodplains, leaving behind a path that waited eons to be seen again.

Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Fossil Giant with a Quiet Secret

Dinosaur Provincial Park has earned global recognition as one of the richest deposits of Late Cretaceous dinosaur bones anywhere on Earth. For over a century, paleontologists have combed its rugged terrain, collecting the remains of massive ceratopsians, duck-billed hadrosaurs, fearsome tyrannosaurs, and more. Yet, in all that time, something curious remained elusive: footprints.

While bones tell us who lived, how big they were, and how they died, tracks can reveal something far more intimate—how they lived, how they moved, and whether they did so together. Until now, the park had been nearly silent on this front. That silence was finally broken in the summer of 2024.

Dr. Brian Pickles from the University of Reading, UK, alongside Dr. Phil Bell of the University of New England, Australia, and Dr. Caleb Brown of Canada’s Royal Tyrrell Museum, led a team of students and researchers through the parched rock formations. What they found wasn’t just a fossil. It was a page from a social history long thought unreadable.

A Crowd in the Clay: Footprints of the Unexpected

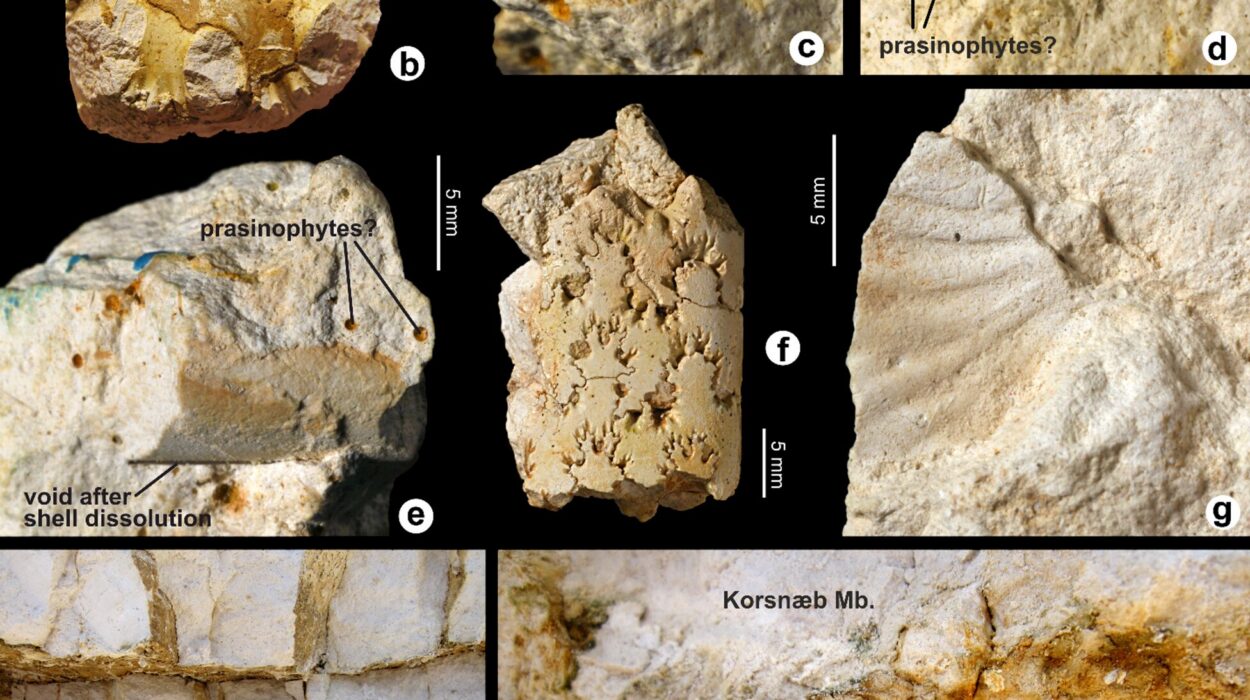

Spread across 29 square meters of ancient sediment were thirteen distinct ceratopsian footprints, pressed deeply into what was once soft, waterlogged earth. These weren’t random scatterings but arranged in a formation unmistakable to trained eyes. At least five horned dinosaurs had walked side by side, their tracks moving in concert. Among them, like a bodyguard in armor, walked a probable ankylosaurid—a heavily armored herbivore with a clubbed tail.

For a moment, it’s not hard to imagine: the grunts and snorts of horned faces in the sunlight, the heavy tread of armored feet, the synchronized sway of bodies moving through a landscape filled with threat. These weren’t just animals passing through the same path at different times. They walked together. And that, for paleontologists, is a profound revelation.

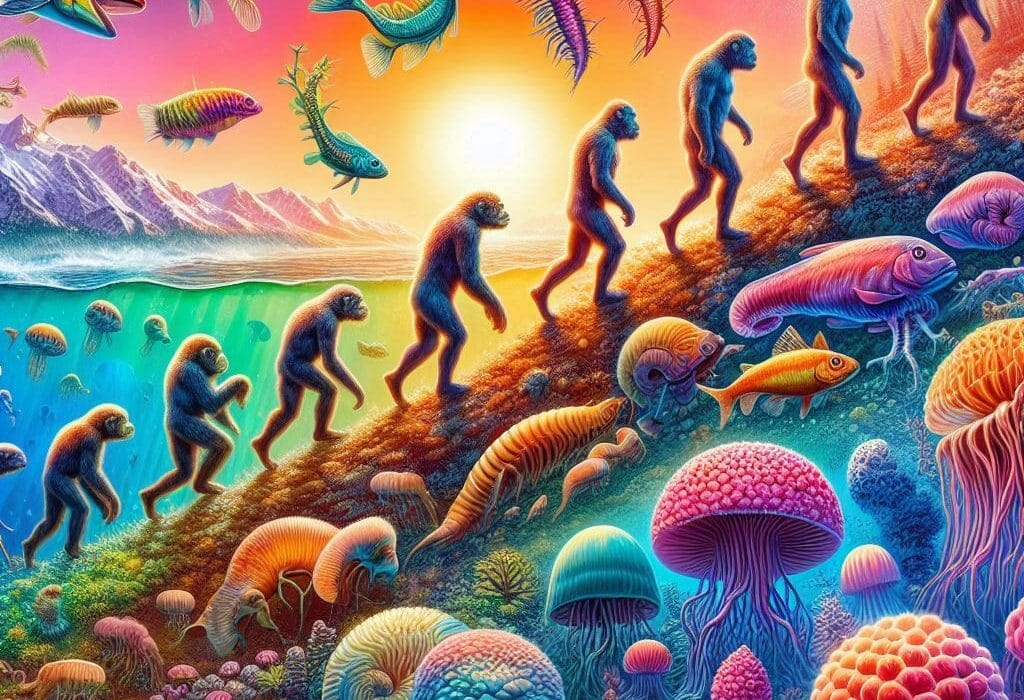

Until now, dinosaur herding behavior had been largely inferred from mass bone beds or aligned trackways of a single species. But this discovery was different. It was the first concrete evidence of a multispecies herd of dinosaurs moving in unison—something more reminiscent of modern African savannahs, where zebras and wildebeest travel side by side, sharing both landscape and danger.

The Chilling Shadow of Predators

Lurking at the edge of this story are two sets of footprints unlike the rest. The team found the parallel tracks of two large tyrannosaurs, walking side by side, perpendicular to the path of the herbivore herd. Their size and stride suggest predators in motion—likely Daspletosaurus or another large tyrannosaurid.

What’s chilling is the possibility of their intent.

Were they merely passing through? Or were they stalking? Were they shadowing the herd, as lions follow prey across African grasslands, waiting for a moment of weakness, a straggler, a slip?

Dr. Phil Bell, who has collected dinosaur bones from the park for nearly 20 years, recalled the moment he spotted the predator prints: “This rim of rock had the look of mud that had been squelched out between your toes,” he said. “The tyrannosaur tracks give the sense that they were really eyeing up the herd, which is a pretty chilling thought.”

Though the tracks don’t show a direct interaction—no panicked dispersal, no sprinting hoofprints—their alignment is suggestive. The fact that these carnivores walked in synchrony raises another fascinating, if speculative, possibility: cooperative behavior. Could tyrannosaurs have hunted in pairs?

For now, that remains a hypothesis. The evidence is tantalizing but not yet conclusive. Still, the juxtaposition of the herd and its possible stalkers paints a dramatic picture of life—and death—on the Cretaceous plains.

Stone Diary of Behavior

What makes footprints so valuable is that they are, in essence, behavioral fossils. Where bones tell of structure and death, tracks speak of action and survival. Each indentation in the sediment captures a single moment—a step, a pause, a press of weight and decision.

The herd’s prints are spaced consistently, with clear alignment and direction, indicating coordinated movement. This doesn’t happen by accident. It implies awareness of surroundings, of companions, and potentially, of threat.

Among the larger prints was a single, smaller track left by a meat-eating dinosaur—likely a troodontid or small dromaeosaurid. Its presence raises even more questions. Was it trailing the herd, following in their path? Or was it simply moving through the same environment on a different mission?

“We’re walking in the footsteps of dinosaurs,” said Dr. Brian Pickles. “Seventy-six million years after they laid them down, we’re finally able to ask how they lived. And sometimes, the stone answers.”

From Dust to Discovery

The discovery unfolded under the blazing sun of a Canadian summer, during a joint international field course. Students from multiple countries hiked over rust-colored ridges and scanned the dusty slopes for signs of something out of place—mudstone with an unnatural shape, a rim where nothing should protrude.

That’s how it began. A strange layer of hardened rock squelched outward like the edge of a boot pressed into wet soil. What followed was painstaking excavation—brushes, chisels, hours of careful scraping. One track led to another, then to another, until a pattern emerged. A trail. A group. A moment in motion, perfectly preserved.

Dr. Caleb Brown, who has spent years studying Dinosaur Provincial Park, was awestruck. “This discovery shows just how much there is still to uncover in dinosaur paleontology,” he said. “This park is one of the best-understood dinosaur assemblages in the world. Yet it’s only now we’re beginning to grasp its full potential for preserving trackways.”

Rethinking Dinosaur Society

These tracks add an important new layer to our understanding of dinosaur behavior. For decades, paleontology has leaned on bone beds and nesting grounds to infer sociality. Some hadrosaur sites suggest group nesting and migration. Ceratopsian skulls show signs of interspecies combat. But this—different species walking together—suggests an even deeper level of behavioral complexity.

It raises powerful questions. Did these dinosaurs recognize each other as part of the same herd? Were there benefits in diversity—greater sensory detection, more eyes, different defenses? Did ankylosaurs provide rear-guard protection, while horned dinosaurs guarded the flanks?

Modern ecosystems are filled with such relationships. Wildebeest and zebras, gazelles and ostriches—they don’t just coexist, they cooperate. Their success depends not only on numbers, but on the complement of their unique strengths. Could dinosaurs have done the same?

Paleontologists are cautious. These are early findings, and the behavior inferred must be supported by more tracksites, more patterns, and more data. But the door is now open. The search is on for other signs of mixed-species herds in the fossil record.

A New Frontier Beneath Our Feet

Since the initial discovery, the team has applied new search images—visual cues that indicate possible track formations—to other parts of the park. Already, several additional tracksites have been identified. Each one holds the promise of further revelations.

The challenge is immense. Time, weather, and erosion erase clues faster than we can find them. Many trackways likely vanished millions of years ago. But some remain, hidden in outcrops, waiting for eyes sharp enough—and minds open enough—to see them.

This discovery reminds us that even in one of the most exhaustively studied fossil regions on Earth, mysteries remain. Beneath every layer of stone could lie a story untold. Every rock, every ridge, every sediment layer could hold the whisper of a footstep, echoing across deep time.

The Living Legacy of Ancient Motion

In the end, what moves us about these tracks is not just what they tell us scientifically, but what they reveal emotionally. There is something deeply human in seeing the trail of a family—or a community—etched into ancient earth. Something familiar in the idea of traveling together for safety, of watching the horizon for danger, of depending on others who are not quite the same.

These dinosaurs are long gone. Their bones lie silent in museums and sediment layers. But here, in this tracksite, they live again—not in static poses, but in motion, in company, in a shared journey across an unforgiving world.

The herd walked on. The predators circled. The mud held their secret. And now, at last, we walk with them again.

Reference: A ceratopsid-dominated tracksite from the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian) at Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324913