In the tropical heat of modern Colombia, amidst thick vegetation and sedimentary rocks, lies one of the most important paleontological treasures in South America: the La Venta fossil site. A place where time hardened into stone and the bones of vanished giants lie buried beneath the surface. Here, in the silence of deep time, bones speak of a world lost—of jungles teeming with monstrous reptiles, birds taller than men, and a landscape alive with the tension of predator and prey.

The middle Miocene epoch, around 12 million years ago, was an age of biological flourish. The Amazon basin was a patchwork of wetlands and rainforests, rivers carved their way across the land like veins, and vertebrate life thrived in dizzying variety. Among these creatures were the terrifying phorusrhacids—colossal, flightless birds often referred to as “terror birds”—and their aquatic counterparts, the mighty caimans. Though one reigned over the land and the other lurked beneath the water, they lived in overlapping worlds. Until recently, it was believed they never truly collided. But new evidence has shattered that assumption.

Ghost of a Struggle in Stone

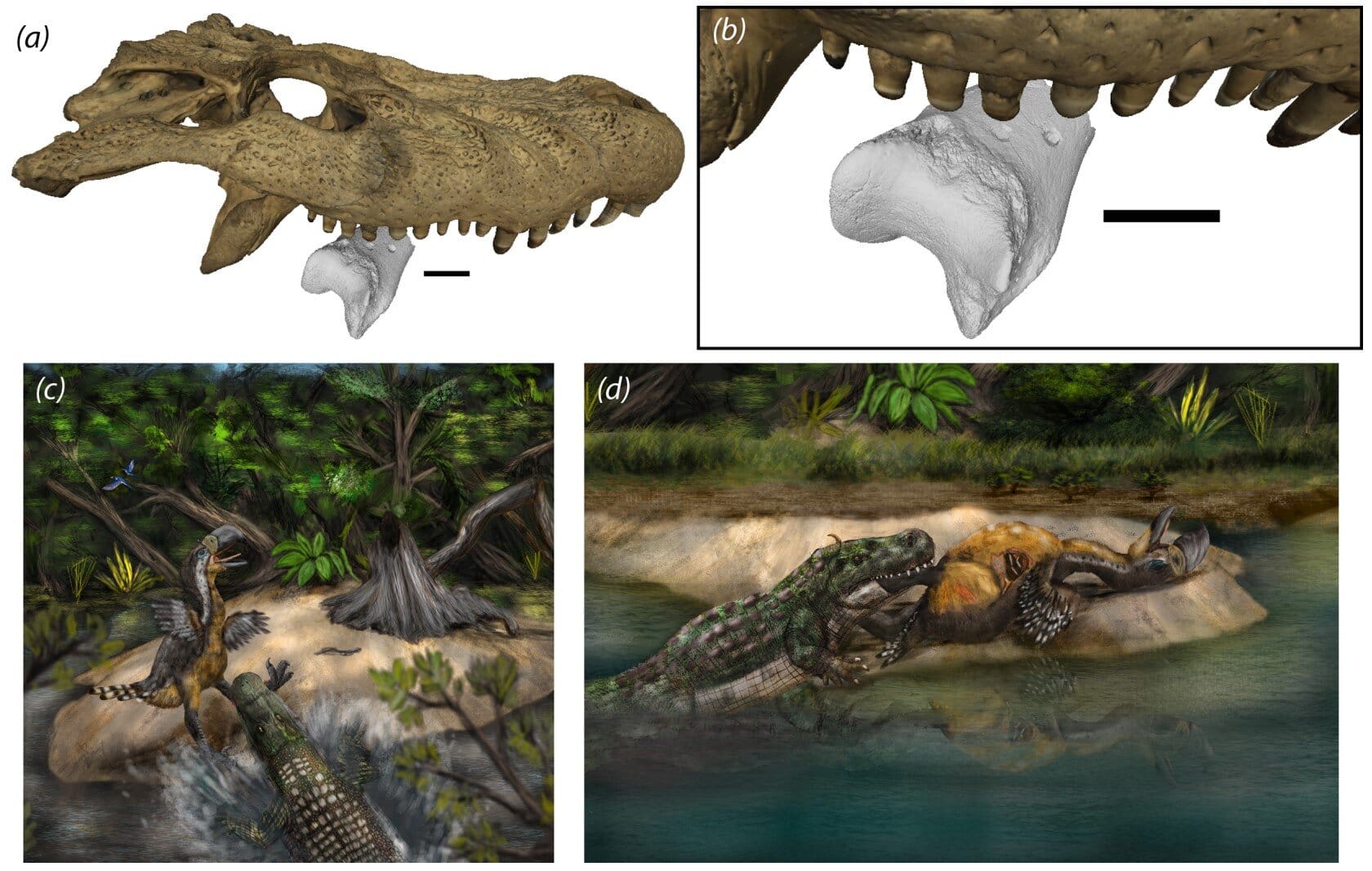

It was a simple leg bone—fossilized, weathered, silent—that changed the story. Found among the fossil beds of La Venta, the bone belonged to a phorusrhacid, a towering predator known for its speed and slashing beak. But this was no ordinary fossil. Embedded in its surface were four deep, unmistakable tooth marks.

The marks were not haphazard scratches or the result of environmental erosion. They were the frozen violence of a long-forgotten attack. Their depth, spacing, and curvature told a story—a story of fangs clamping down, of bone crunching beneath immense force. Using state-of-the-art 3D surface scanning and digital modeling, paleontologists meticulously reconstructed the shape of the jaw responsible.

All clues pointed to one creature: Purussaurus neivensis, a prehistoric caiman and close relative of modern-day crocodilians. But Purussaurus was no ordinary reptile. Stretching up to 10 meters long and weighing several tons, it was a behemoth of swamps and rivers, an apex predator of near-mythic proportions. In its time, it ruled the waterways like a living nightmare, ambushing prey with devastating speed and power.

Now, for the first time, we had evidence that two apex predators—one from land, one from water—had met in mortal combat.

A Deadly Intersection of Worlds

To understand how such a clash could occur, we must first step into their world. The Miocene landscape of La Venta was dynamic, where lush tropical forests bordered vast wetlands and meandering rivers. These transitional zones—where land and water met—were rich with life, but also fraught with danger. For a terrestrial predator like the terror bird, these areas were both a hunting ground and a hazard.

Unlike the modern ecosystems of Africa and Asia, where lions and crocodiles often contend at watering holes, scientists had little direct evidence of similar interactions in prehistoric South America—until now. The study, published in Biology Letters, offered a sobering revelation: even the terror bird, a creature whose name alone conjures dominance, was vulnerable.

The fossil bore no signs of healing. This wasn’t a bite survived. It was a bite endured in the final moments of life. Whether the caiman struck from concealment in shallow water, ambushing the bird as it drank, or scavenged its carcass post-mortem is unclear. But one thing is certain—the terror bird did not walk away.

Death at the Water’s Edge

There’s a haunting familiarity in this scenario. In the wild places of today—rivers in Africa, marshes in India—apex predators converge at the water’s edge. Lions, jaguars, and elephants venture into croc-filled waters to drink, bathe, or hunt. In these moments, even kings must tread carefully. Water is life, but water is also where death waits with open jaws.

The study’s authors suggest that similar behavior patterns existed during the Miocene. In dry seasons, waterholes would become oases of life and battlegrounds of survival. Terrestrial predators, driven by thirst or opportunity, would approach the banks, placing themselves within striking distance of aquatic hunters. For a moment, the balance of power shifted.

This fossilized leg, bearing the unmistakable scars of predation, is more than just a bone—it’s a snapshot of that fragile moment, that deadly intersection where two realms overlapped.

When Dominance Isn’t Absolute

The terror bird was no weakling. Phorusrhacids could stand up to 3 meters tall and were built for speed and brutality. Their hooked beaks could puncture skulls, and their legs were adapted for both running and delivering devastating kicks. In their ecosystem, they were unrivaled land predators.

But evolution doesn’t offer safe harbors. It only offers trade-offs. The bird’s power lay in its agility, its reach, its land-bound dominance. In water or on muddy terrain, those advantages evaporated. It’s easy to imagine a bird stalking the edge of a shrinking pond during dry season, searching for prey—or perhaps simply for water. And then, without warning, the ripple of the surface becomes a rush of power and teeth. In a moment, the predator becomes prey.

That moment is etched into stone now, as if the Earth itself remembered.

The Complexity of Prehistoric Life

It’s tempting to simplify prehistoric ecosystems into neat hierarchies: the biggest creatures ruled, smaller ones fled. But real life, whether ancient or modern, is far more nuanced. This discovery complicates our understanding of who hunted whom. It reminds us that even the most formidable predator can be vulnerable in the wrong context.

The researchers caution that we may never know for certain whether this was an act of hunting or scavenging. A dying or recently dead terror bird might have been easy pickings for a hungry caiman. Yet the precise nature of the bite marks, and their placement on a weight-bearing leg bone, hint at a struggle—one that may have occurred while the bird was still alive and resisting.

Encounters like this may have been rare, or perhaps they were more common than we realize. Fossilization is an imperfect narrator. Bones break. Evidence disappears. But every now and then, a scene is preserved well enough to give us a glimpse behind the curtain.

Predator vs. Predator: A War Without Winners

What’s especially fascinating is that this fossil forces us to challenge our assumptions about competition. We often think of apex predators as existing in parallel, rarely intersecting, each occupying its own domain. But ecosystems don’t function in isolation. Rivers flood. Prey migrates. Droughts come. Territories blur.

Even in the present day, scientists have observed crocodiles taking down lions in southern Africa. Jaguars, too, have learned to kill caimans in the Pantanal wetlands. When food is scarce or territories overlap, boundaries dissolve. Risk increases. Sometimes the hunter gambles and loses.

The terror bird’s fossil tells us that this dynamic—this lethal game of roulette—has existed for millions of years.

The Legacy of La Venta

La Venta continues to astonish paleontologists with its depth and diversity. Beyond terror birds and caimans, the site has yielded fossils of ancient monkeys, giant sloths, early bats, turtles, and ungulates. Each fossil offers a thread, and together they weave a tapestry of ancient life. But the terror bird’s leg, marked by the jaws of a caiman, stands apart. It speaks not just of death, but of a dramatic story—a narrative that once played out in real time under the tropical sun.

It’s a rare thing in paleontology to find direct evidence of an interaction between two specific creatures. Far more often, scientists must infer relationships from anatomical features, stomach contents, or coprolites (fossilized feces). To find a fossil that bears the violence of a direct encounter is extraordinary. To find one involving two of the most fearsome predators of the Miocene is, frankly, astonishing.

Echoes of the Ancient Jungle

In the end, the terror bird and Purussaurus neivensis are more than just long-dead creatures. They are symbols of a time when the natural world was wilder, stranger, more brutal—and yet still governed by the same fundamental laws that shape life today.

Predators still stalk riverbanks. Prey still risks everything for a sip of water. Ecosystems still pivot on fragile balances, and life, as always, hangs by a thread.

The terror bird’s fate is a reminder that no creature is invincible. Not in the Miocene. Not now. In the grand narrative of evolution, dominance is temporary, and survival is a game of inches—played out in a world that always has surprises waiting in the undergrowth.

And sometimes, those surprises have teeth.

Reference: Andres Link et al, Direct evidence of trophic interaction between a crocodyliform and a large terror bird in the Middle Miocene of La Venta, Colombia, Biology Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2025.0113