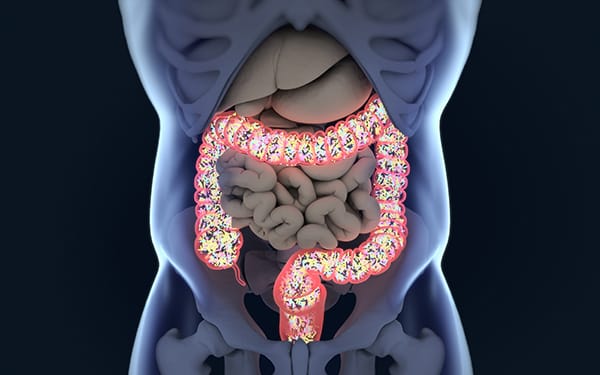

Deep inside the human body, hidden from view and easily forgotten, lies a vast and bustling ecosystem. It is a universe unto itself, teeming with trillions of microscopic inhabitants—bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea—living in a complex and dynamic harmony. This is the gut microbiome, and for many decades it was overlooked, regarded as little more than a digestive curiosity. But modern science has changed all of that. The gut microbiome is now understood to be one of the most important regulators of human health.

At the center of this microbial world are probiotics—living organisms that, when consumed in adequate amounts, confer health benefits on their host. Probiotics have emerged from the shadows of yogurt advertisements and health food fads to become one of the most promising frontiers in medical research. Their influence stretches far beyond digestion, touching the immune system, the brain, and even our emotional well-being.

The journey to understanding how probiotics affect gut health is both deeply personal and globally relevant. It is a story of ancient traditions meeting cutting-edge science, of human vulnerability and biological resilience. It begins, quite literally, at birth—and continues every moment we are alive.

The Microbial Origins of Life and Health

Before we are even born, our bodies begin to be colonized by microbes. For a long time, scientists believed the womb was a sterile environment, but recent research suggests that microbial exposure may begin in utero. The passage through the birth canal, however, is the baby’s first major microbial baptism. During vaginal delivery, infants are coated in maternal bacteria that seed their intestines, beginning the process of building a microbiome that will support them for life.

Within days, the gut becomes a thriving community. Breast milk, once thought to be a mere source of nutrients, is now known to contain prebiotics—specialized fibers that nourish beneficial bacteria—as well as live bacteria themselves. This early microbial exposure has lasting effects. Infants delivered via Cesarean section or fed formula instead of breast milk often show different microbiome compositions, and studies have linked these variations to increased risks for allergies, asthma, and autoimmune conditions later in life.

The first few years of life are critical. During this time, the microbiome undergoes dramatic shifts in response to diet, environment, and illness. By the age of three, a child’s gut microbiota begins to resemble that of an adult. Throughout life, the microbial community continues to evolve, influenced by everything we eat, the medications we take, and even our stress levels.

It is within this context—a lifetime of microbial interaction—that probiotics emerge as allies.

What Exactly Are Probiotics?

The term “probiotic” comes from the Greek “pro bios,” meaning “for life.” Unlike antibiotics, which are designed to kill bacteria, probiotics aim to support and enhance the microbial balance of the body. Most probiotics are bacteria—especially species from the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium—but some are yeasts like Saccharomyces boulardii. These microbes are typically ingested through fermented foods or supplements.

The key requirement for a microorganism to be considered a probiotic is that it must survive the harsh conditions of the digestive tract and exert a measurable benefit on the host. This is no small feat. After all, the human stomach is an acidic crucible designed to destroy invaders. Only the hardiest strains survive the journey and manage to colonize the intestines, even if only temporarily.

Once there, probiotics work in subtle but powerful ways. They produce compounds that inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, modulate immune responses, and help maintain the integrity of the gut lining. They even produce neurotransmitters like serotonin, influencing mood and cognition. In essence, probiotics are peacekeepers in the ever-changing world of the gut, restoring balance when it falters.

Gut Health as a Mirror of Whole-Body Health

The idea that all health begins in the gut is not new. Over 2,000 years ago, Hippocrates—the father of medicine—famously proclaimed that “all disease begins in the gut.” Today, this ancient insight is supported by modern science. An unhealthy gut has been linked to a wide range of conditions, from digestive disorders like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), to metabolic diseases like obesity and type 2 diabetes, to neuropsychiatric illnesses including anxiety, depression, and even autism.

The gut is not an isolated tube; it is an integrated part of a complex physiological network. It is lined by a single layer of epithelial cells that serve as a barrier between the internal world of the body and the external environment of the gut lumen. This barrier is crucial. When it becomes compromised—a condition known as “leaky gut”—toxins, undigested food particles, and bacteria can enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation.

Probiotics help maintain and repair this barrier. They promote the production of mucus, which protects the gut lining, and stimulate the release of tight junction proteins that hold epithelial cells together. They also compete with pathogenic microbes for space and nutrients, reducing the risk of infections and chronic inflammation.

Gut health is also inseparably tied to the immune system. Approximately 70% of immune cells reside in the gastrointestinal tract. Here, they learn to distinguish between friend and foe. Probiotics can educate these immune cells, enhancing their ability to respond to pathogens without overreacting to harmless substances—an effect that may reduce the risk of allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases.

Fermented Foods: Ancient Wisdom Reimagined

Long before the term “probiotic” existed, humans were consuming fermented foods rich in beneficial microbes. Yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, miso, and tempeh are all examples of traditional foods that have nourished civilizations for centuries. In many cultures, these foods were revered not only for their taste and preservation qualities but also for their health-promoting properties.

The fermentation process transforms raw ingredients into complex, flavorful, and bioactive foods. As microbes break down sugars and starches, they produce acids, gases, and bioactive peptides that can enhance digestion, support immunity, and even modulate blood sugar levels.

Scientific studies have confirmed many of these traditional beliefs. Regular consumption of fermented foods has been associated with lower rates of gastrointestinal infections, improved lactose digestion, and enhanced immune responses. Unlike isolated probiotic supplements, fermented foods provide a diverse array of microbial species along with fiber, vitamins, and polyphenols that further support gut health.

However, not all fermented foods are created equal. Some, like pickles made with vinegar instead of live cultures, offer little probiotic value. Pasteurization can also destroy beneficial microbes. For this reason, raw and traditionally fermented products are often recommended for those seeking probiotic benefits.

Probiotics and the Gut-Brain Axis

One of the most astonishing discoveries in modern biology is the existence of the gut-brain axis—a bidirectional communication pathway linking the gut and the brain. This pathway involves multiple channels: neural (via the vagus nerve), hormonal, immune, and microbial. It turns out that the bacteria in our gut don’t just help us digest food; they also influence how we feel, think, and behave.

The gut produces more than 90% of the body’s serotonin—a neurotransmitter critical for mood regulation. Probiotics can influence the synthesis and availability of serotonin and other neuroactive compounds, such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), dopamine, and acetylcholine. These microbial interactions may help explain why disturbances in the microbiome have been linked to anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline.

In clinical trials, certain probiotic strains have demonstrated modest but measurable effects on mood and mental health. These “psychobiotics” may help alleviate symptoms of depression, reduce stress-related cortisol levels, and improve sleep quality. Though not a replacement for traditional therapy, probiotics represent a promising adjunct treatment in the growing field of nutritional psychiatry.

Challenges in Probiotic Science

While the excitement around probiotics is well-deserved, the field is not without controversy. Many commercial products make sweeping health claims without sufficient scientific backing. The effects of probiotics are often strain-specific, and not all strains are beneficial for all individuals or conditions. What helps one person may do nothing for another, depending on the unique composition of their gut microbiome.

There is also the issue of viability. Probiotics must remain alive through processing, packaging, and storage—and then survive the acidic gauntlet of the stomach to reach the intestines. Not all products meet these criteria. Regulatory oversight is limited in many countries, and quality control can vary widely between brands.

Moreover, the long-term colonization of probiotics in the gut remains a topic of debate. Some studies suggest that probiotics do not establish permanent residence but instead exert their benefits while passing through. This transient effect means that continued use may be necessary to sustain the benefits.

Despite these limitations, the overall trend in probiotic research is positive. As scientists develop more sophisticated tools to analyze the microbiome, they are uncovering mechanisms of action, identifying effective strains, and personalizing interventions. The future of probiotic therapy lies in precision—matching specific strains to individual microbiomes and health conditions.

Prebiotics and Synbiotics: Feeding the Good Guys

Probiotics do not work alone. Like any living organism, they require sustenance. This is where prebiotics come in. Prebiotics are nondigestible fibers that feed beneficial bacteria, helping them grow and thrive. Common sources include chicory root, garlic, onions, asparagus, and bananas. When consumed together, probiotics and prebiotics form what is known as a “synbiotic” relationship—each enhancing the other’s effectiveness.

This synergy is essential for long-term gut health. A diet rich in diverse plant fibers supports a diverse microbiome, which in turn supports a resilient immune system, efficient metabolism, and balanced mood. Synbiotic formulations are being developed to target specific health conditions, from irritable bowel syndrome to antibiotic-associated diarrhea to metabolic syndrome.

Antibiotics and Microbial Recovery

Antibiotics are among the most powerful tools in modern medicine, saving countless lives from bacterial infections. But they are a double-edged sword. Broad-spectrum antibiotics do not discriminate between pathogenic and beneficial bacteria. As a result, they can devastate the gut microbiome, leading to diarrhea, opportunistic infections like Clostridioides difficile, and long-term alterations in microbial composition.

Probiotics have shown promise in mitigating some of these side effects. Administering certain probiotic strains during or after antibiotic treatment can help restore microbial balance, reduce inflammation, and accelerate recovery. However, timing and strain selection are critical, and more research is needed to develop clear guidelines.

Looking to the Future: Personalized Microbiome Medicine

The dream of personalized medicine—tailoring treatment to the individual—is becoming a reality in the field of microbiome research. Advanced sequencing technologies now allow scientists to analyze the microbial composition of an individual’s gut with astonishing precision. This opens the door to custom-designed probiotic therapies based on a person’s unique microbial profile.

Researchers are also exploring the therapeutic potential of “next-generation probiotics”—microbial strains not traditionally found in foods but isolated from healthy human guts. These include Akkermansia muciniphila, known for its role in metabolic regulation, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a potent anti-inflammatory microbe. Clinical trials are underway to test these novel strains in conditions ranging from obesity to inflammatory bowel disease to Parkinson’s.

Another exciting development is the use of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), in which stool from a healthy donor is transplanted into a recipient to restore microbial balance. While FMT is still considered experimental for most conditions, it has shown remarkable success in treating recurrent C. difficile infections and holds promise for other diseases as well.

A Gentle Revolution

The story of probiotics is a story of healing—not just of the body, but of the relationship between humans and the microbial world. For centuries, we waged war on microbes, viewing them solely as enemies to be eradicated. But the truth is far more nuanced. We are not separate from our microbes; we are symbiotic with them. Our health depends on their health.

As we move deeper into the 21st century, this understanding is transforming medicine, nutrition, and even our view of what it means to be human. The gut is no longer a silent organ; it is a vibrant ecosystem, a guardian of immunity, a mirror of mental health, and a guide to longevity.

Probiotics are not a cure-all, nor are they a fad. They are living testaments to the ancient wisdom that health begins within—and to the modern science that proves it. By nourishing our microbial allies, we nourish ourselves. And in doing so, we may discover that the most profound revolutions in health are not loud and violent, but quiet, microscopic, and already inside us.