Deep beneath the surface of a quiet German hillside, where dark layers of oil shale preserve whispers from Earth’s distant past, scientists have uncovered a voice from 47 million years ago—though this voice hasn’t sung in eons. Preserved with exquisite detail in the sedimentary cradle of the Messel Pit, the newly discovered cicada species Eoplatypleura messelensis has emerged as both a scientific marvel and a critical missing piece in the story of insect evolution.

For the first time, researchers have identified a true cicada fossil from the Messel Pit, a UNESCO World Heritage Site renowned for its rich tapestry of Eocene-era life. This striking find, published in the journal Scientific Reports, reveals the earliest known representative of the modern cicada subfamily Cicadinae and marks a landmark moment in the reconstruction of ancient ecosystems.

A Cicada from Deep Time

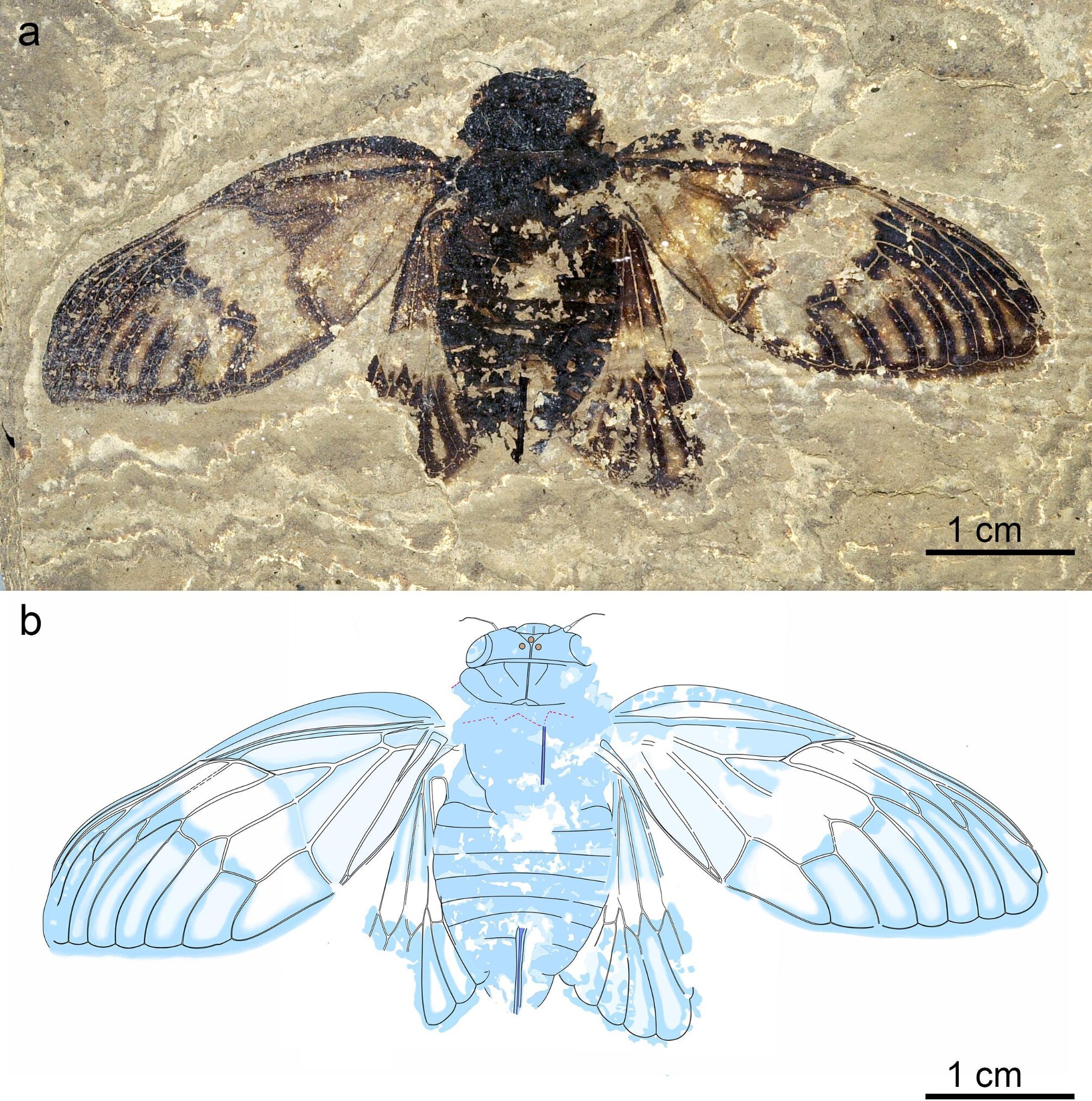

The fossil, an adult female with a body length of 26.5 millimeters and a wingspan reaching 68.2 millimeters, offers a rare glimpse into the world of buzzing insects as they existed nearly 50 million years ago. Named Eoplatypleura messelensis, this prehistoric creature belonged to the tribe Platypleurini—an ecologically versatile group of cicadas still thriving today in forests and scrublands from Africa to Asia.

But unlike their modern descendants, whose rhythmic calls punctuate summer air, this cicada speaks only through the rock in which it was entombed. Its preserved form, complete with a broad head, subtly curved wings, and faintly patterned membranes, has given researchers an invaluable window into the biology and distribution of ancient true cicadas.

“The family Cicadidae is incredibly diverse today, but fossil records are astonishingly scarce,” notes Dr. Sonja Wedmann of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt. “This new find is extraordinary—not only is it the first fossil of its group described from the Messel Pit, it also represents the oldest known record of the Cicadinae subfamily globally.”

The Messel Pit: A Paleontological Time Capsule

Located near the German city of Darmstadt, the Messel Pit was once a quiet volcanic lake surrounded by subtropical vegetation. Around 47 million years ago, the lakebed became a trap for an astonishing variety of life—fish, reptiles, birds, mammals, and insects—all preserved in the oxygen-poor sediments that accumulated year after year. Today, the site is a global treasure trove of Eocene biodiversity, renowned for its exceptional fossil preservation.

Insects from this period are especially rare and valuable. Their delicate exoskeletons and soft tissues usually vanish in the geological record, leaving only the hardiest fragments behind. But the Messel Pit, with its fine-grained shale and gentle depositional processes, provides an unparalleled record of ancient arthropods.

The discovery of Eoplatypleura messelensis adds a vital puzzle piece to the picture of insect evolution in the early Cenozoic era. It confirms that true cicadas had already established a foothold in Eurasia during the Eocene and were possibly beginning to diversify into the myriad species we see today.

A Mosaic of Ancient Adaptations

The fossil’s wings, broad and ornately veined, show patterns reminiscent of modern cicadas in the Platypleurini tribe. These patterns, researchers believe, served a practical purpose: camouflage. During the Eocene, the Messel region was cloaked in lush subtropical flora—palm-like plants, flowering trees, dense underbrush. A cicada resting on a leaf needed to remain hidden from predators, and patterned wings would have offered an evolutionary advantage.

“Today’s Platypleurini species use wing coloration to blend into their forest surroundings,” says Dr. Hui Jiang, lead author of the study, who conducted her research at the Senckenberg Messel Station. “It’s likely that Eoplatypleura messelensis used its wing patterns in much the same way, reflecting a remarkable ecological continuity across tens of millions of years.”

Even more intriguing is what the fossil suggests about the cicada’s behavior. Although the specimen is female—and therefore would not have produced the characteristic mating songs—her morphology strongly implies that males of the species did. The curved forewings and compact body structure are traits associated with species that use sound to communicate, adding an auditory dimension to our understanding of this ancient insect’s world.

A Gap Closed in the Cicada Lineage

Cicadas are among the oldest and most successful insect lineages, with roots tracing back over 200 million years. Yet, despite their longevity and diversity—more than 3,000 species exist today—their fossil record is frustratingly sparse. This has made it difficult for entomologists and evolutionary biologists to trace the development of key cicada traits, such as their complex life cycles, specialized vocal apparatus, and ecological adaptations.

Before this discovery, only 44 cicada fossils had been identified from the entire Cenozoic era, the geological period beginning 66 million years ago and continuing to the present. Most were fragmentary or poorly preserved, offering only limited insights. Eoplatypleura messelensis, in contrast, is nearly complete, richly detailed, and housed within one of the best-documented fossil beds on Earth.

“This fossil helps close a significant gap in our knowledge,” says Dr. Wedmann. “It shows that the Platypleurini group was already present in Europe by the middle Eocene and suggests that modern cicadas began diversifying earlier than previously thought. This species gives us a crucial reference point for future studies on cicada evolution and biogeography.”

Fossils as Time Travelers

Beyond its biological significance, Eoplatypleura messelensis carries a broader message about the role of fossils in understanding Earth’s history. Fossils are not merely relics of dead organisms; they are storytellers that reveal how life on Earth has responded to climate shifts, mass extinctions, and ecological upheavals.

The Eocene epoch was a time of dramatic change. Following the extinction of the dinosaurs, mammals, birds, and insects surged into newly available ecological niches. Warm global temperatures supported lush vegetation across much of the planet, and new forms of life proliferated. Understanding how organisms like cicadas adapted to these conditions helps scientists decode the evolutionary pressures that shaped modern ecosystems.

Moreover, by comparing ancient cicadas to their living counterparts, researchers can study how traits such as sound production, camouflage, and seasonal emergence have evolved—or stayed remarkably the same—over tens of millions of years.

A Scientific Milestone with Musical Roots

There is a poetic irony in the discovery of a cicada fossil—a creature defined by its song—forever frozen in silence. Cicadas are among the few insects whose acoustic signals play a central role in their life history. Their mating calls, produced by specialized structures called tymbals, are complex, species-specific, and incredibly loud—reaching over 100 decibels in some species.

The absence of sound in the fossil record makes studying this behavior difficult, but fossils like Eoplatypleura messelensis provide tantalizing anatomical clues. The preserved wing structures, body proportions, and placement of musculature can suggest the presence of sound-producing adaptations. This allows scientists to reconstruct the likely behavior of long-extinct species and trace the origins of cicadas’ musical legacy.

Dr. Jiang and her colleagues believe that Eoplatypleura messelensis represents not just a physical ancestor to modern cicadas, but a cultural one as well—an early member of the buzzing, singing insect choir that would eventually spread across continents.

Echoes into the Future

The significance of this discovery extends beyond paleontology. As ecosystems around the world face the mounting pressures of climate change, habitat loss, and species extinction, understanding the long-term resilience and adaptability of insect lineages like cicadas becomes more important than ever.

Cicadas have survived mass extinctions, ice ages, and geological upheaval. They have evolved elaborate strategies to thrive—some emerging only once every 13 or 17 years in synchronous pulses, others developing cryptic coloration or exploiting narrow ecological niches. Studying their ancient relatives can provide key insights into what makes insects so adaptable—and what might threaten that adaptability in the future.

The fossil of Eoplatypleura messelensis reminds us that even the smallest creatures leave legacies etched in stone. Its wings, frozen in mid-fold, carry the genetic echoes of millions of years of evolution. Its patterned membranes once fluttered in a forest long vanished. And though it no longer sings, its silence speaks volumes.

As Dr. Wedmann eloquently puts it: “Every new fossil from the Messel Pit is a treasure. Insects form the foundation of biodiversity, and their fossil record helps us understand how life has changed—and endured—through time. Eoplatypleura messelensis is more than just a cicada. It’s a message from Earth’s past, reminding us of the beauty, complexity, and fragility of the natural world.”

Reference: Jiang, H. et al. Sounds from the Eocene: the first singing cicada from the Messel Pit, Germany. Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-94099-7 www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-94099-7.