For decades, it was little more than a whisper of wings sealed in stone—a mysterious imprint, faded and silent, resting quietly in a drawer of the Museum of Unique Insect Fossils in Japan. Labeled and stored away since its discovery in 1988, the fossil had escaped scientific spotlight for more than 35 years. But now, that fossil has broken its long silence, offering up secrets from a forgotten world.

In a recent study published on May 2 in the journal Paleontological Research, scientists have finally lifted the veil on this “extremely rare” discovery. What they found was more than a new species—it was the ghost of an ancient butterfly, a relic from a vanished age. Welcome to the story of Tacola kamitanii, Japan’s extinct butterfly and the youngest known fossil of its kind.

A Stone Whisper from the Ice Age

Unearthed in the town of Shin’onsen, nestled in northeastern Hyogo Prefecture—a serene region just over 115 miles from the bustling heart of Osaka—the fossil was found in a sedimentary rock layer dating back to the Early Pleistocene epoch. That places it between 2.6 million and 1.8 million years ago, a time when woolly mammoths roamed the Earth, early humans fashioned stone tools, and ice sheets began their relentless march across the globe.

Within this shifting climate, Tacola kamitanii fluttered through warm-to-mild forests, perhaps sipping nectar beneath a subtropical sun or laying eggs along the edges of ancient leaves. Then, suddenly or gradually, its story ended. Yet the butterfly left behind a delicate echo—an impression in mud that would harden over millennia into stone.

A Remarkable Revelation

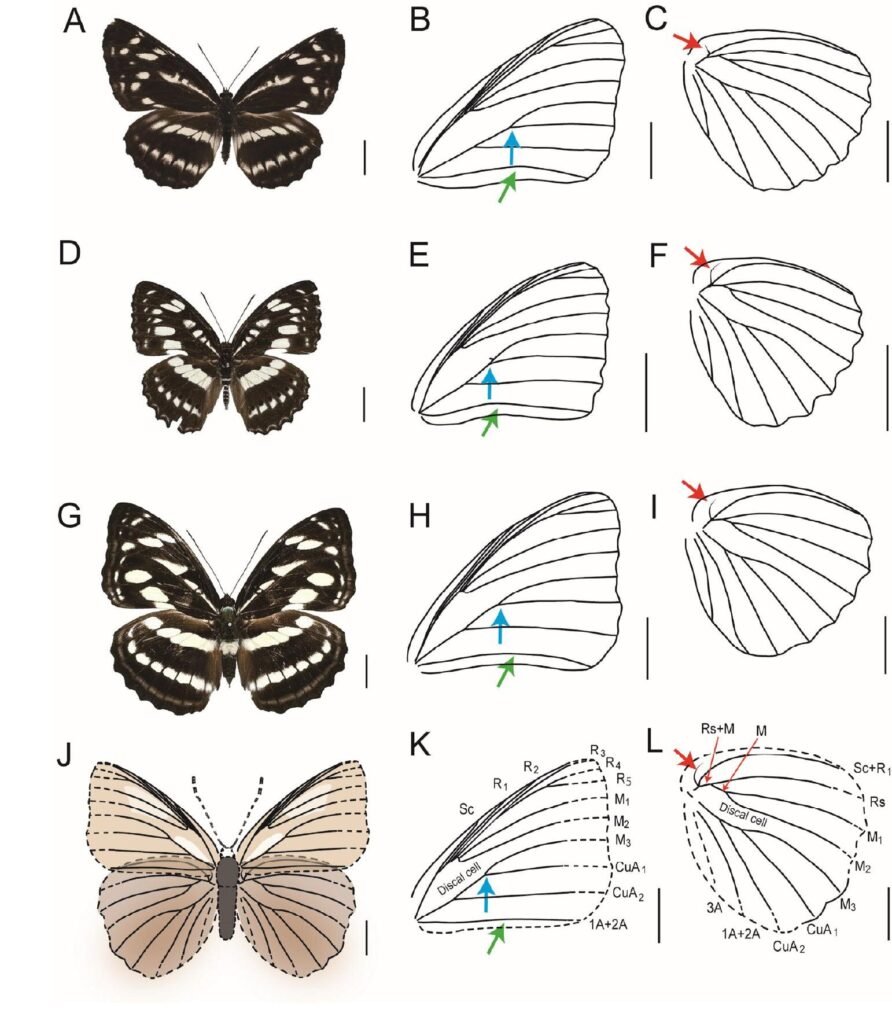

According to lead researchers Hiroaki Aiba, Yui Takahashi, and Kotaro Saito, the fossil represents the first named butterfly from the Limenitidini subfamily—a vibrant group that includes living species like viceroys and admirals. And while the fossilized butterfly no longer beats its wings, its legacy stretches wide: Tacola kamitanii is also the first butterfly fossil ever recorded from the Early Pleistocene.

What makes this discovery so remarkable is not just its age, but its sheer rarity. Butterfly fossils are notoriously difficult to come by. Unlike beetles with sturdy shells or ants with compact frames, butterflies are fragile to the extreme. Their delicate, paper-thin wings and lightweight bodies rarely withstand the brutal crush of time, erosion, or fossilization. The odds of a butterfly fossil surviving millions of years are astronomically slim. That’s why, in the world of paleontology, such discoveries are often described as miracles of preservation.

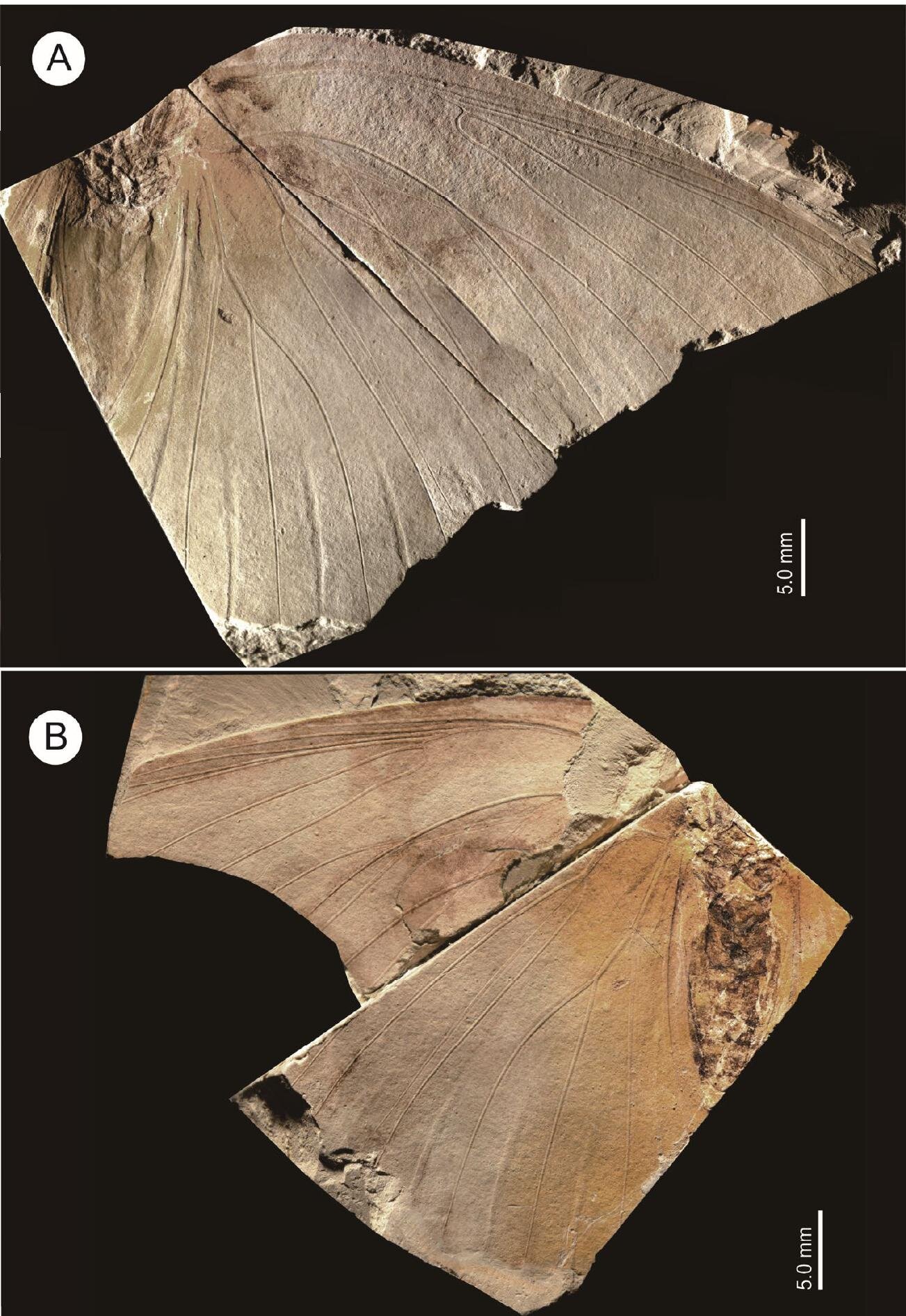

Beauty Preserved in Stone

The fossil of Tacola kamitanii is thought to belong to a female, distinguished by its robust body and unusually thick abdomen. These characteristics are typical of female butterflies preparing to reproduce, suggesting she may have been laying eggs when she met her demise—perhaps caught in a sudden mudslide or buried by falling ash or sediment. Whatever the cause, her final moment became immortalized in geological history.

Most striking of all is her wingspan, which researchers estimate stretched an impressive 3.5 inches across—“remarkably large” for a butterfly of her subfamily. The fossil clearly displays the outline of both the body and the wings, a rare level of detail that allowed scientists to determine not just its species but its likely behavior, habitat, and evolutionary importance.

An Ancient World Reconstructed

During the Late Pliocene and into the Early Pleistocene, the world was undergoing dramatic change. Global temperatures dropped, glaciers expanded, and sea levels fell. Yet in the temperate forests of what is now Japan, biodiversity bloomed. Butterflies such as Tacola kamitanii likely thrived in lush, forested environments with mild winters and humid summers.

As Earth’s climate began its march toward colder extremes, habitats shifted and species were forced to adapt, migrate, or die. The discovery of Tacola kamitanii suggests that members of the Tacola genus, previously believed to have been limited to Southeast Asia, once spread much farther north than previously assumed. This opens a new window into the migratory patterns and ecological dynamics of prehistoric butterflies—and suggests that Tacola butterflies were more adaptable and widespread than modern distributions indicate.

The Man Behind the Name

The fossil’s scientific name, Tacola kamitanii, pays tribute to Kiyoshi Kamitani, the man who discovered the fossil more than three decades ago. His find—once considered little more than a curiosity—has now become a scientific treasure. Kamitani’s name will forever flutter in the annals of entomological history, tied to a butterfly that outlived its own era in the most improbable way.

Such gestures are common in taxonomy but carry special meaning in cases like this. Naming a species is not just an act of classification—it’s an act of resurrection. It brings the dead into the realm of the living, ensuring that Tacola kamitanii is not merely a pattern pressed into stone, but a being with identity, lineage, and narrative.

Echoes from a Lost Sky

Why do we care about a single butterfly fossil, discovered decades ago, quietly sleeping in a museum? Because within that fossil lies a fragment of our planet’s untold story. Each fossil is a page from Earth’s ancient biography. And in the case of butterflies, the pages are few and the words delicate.

Tacola kamitanii forces us to confront the fragility of life—not just in its biological form, but in its memory. Most living things leave no trace. To become a fossil is to win a lottery of cosmic odds. And to be recognized, named, and placed in the tree of life millions of years later is nothing short of poetic justice.

For scientists, the discovery adds a vital data point in understanding insect evolution. For the rest of us, it’s a humbling reminder of nature’s beauty and brevity. A butterfly lives for weeks. This one, through rock and time, has lived for over two million years.

Japan’s Forgotten Fossil Legacy

Japan is not often considered a fossil-rich land in the popular imagination. Yet its layered geological history tells a different story. From marine fossils to mammalian bones and now delicate butterfly wings, Japan’s fossil record is a mosaic of past environments and vanished creatures.

The town of Shin’onsen—its name literally meaning “new hot spring”—is located in a region known for geothermal activity, scenic coastline, and natural beauty. With this discovery, it adds something more: a connection to the deep past, a place where time, earth, and life converged in just the right way to capture a fleeting moment forever.

The Museum of Unique Insect Fossils, where Tacola kamitanii lay waiting all these years, may now see a renewed wave of interest. In a world rushing forward, there is something deeply grounding about a story that took millions of years to tell.

Science, Serendipity, and Second Chances

The story of Tacola kamitanii is one of patience, persistence, and the peculiar magic of overlooked treasures. Had it not been for the curiosity of researchers like Aiba, Takahashi, and Saito, the fossil might have remained anonymous forever. Instead, it now has a name, a story, and a place in the grand mosaic of life on Earth.

Insects are the silent workers of ecosystems, often ignored by both science and society. Yet they hold the keys to understanding evolution, adaptation, and extinction. The fossil of Tacola kamitanii doesn’t just illuminate the past—it challenges us to think more deeply about the present and future of our planet’s biodiversity.

Final Flutter

In the end, Tacola kamitanii is more than a scientific curiosity—it’s a symbol. It represents the unknown lives that came before us, the quiet drama of extinction, and the enduring wonder of discovery. Its wings no longer flutter through the forests of ancient Japan, but in the minds of those who study it, they beat again—softly, but with profound resonance.

From a slab of stone in a quiet corner of a museum, an extinct butterfly has returned to the world stage—not with a roar, but with a whisper of wings across time.

Reference: Hiroaki Aiba et al, New species of fossil butterfly (Nymphalidae: Limenitidinae) from the Upper Pliocene to Lower Pleistocene Teragi Group, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, Paleontological Research (2025). DOI: 10.2517/prpsj.240023