For thousands of years, locusts have been nature’s most merciless army. They sweep across fields in black waves, eating everything in their path, leaving famine and ruin behind. Farmers throughout history—from ancient Egypt to 21st-century Africa—have stood helpless before these ravenous swarms. In scripture, they were one of the ten plagues. In science, they’ve long been a mystery. How does one harmless insect suddenly become part of a synchronized, sky-darkening horde?

Now, a team of scientists in China has made a discovery that could rewrite that story.

In a groundbreaking new study published in Nature, a collaborative team of zoologists, molecular engineers, and pest control experts from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Peking University has uncovered the biological mechanism behind one of the locust’s most destructive traits: the ability to switch from a solitary, passive lifestyle to a frenzied, swarming state.

Their work identifies the chemical trigger of this transformation—and may offer a new way to stop locust plagues before they even begin.

The Chemistry of a Plague

Back in 2020, researchers discovered that a pheromone called 4VA—short for 4-vinylanisole—plays a central role in the locust’s dramatic behavioral change. When this compound is released, it acts as a chemical rallying cry. Nearby locusts detect it, draw closer, and begin to swarm. A quiet population becomes a violent mob.

But until now, scientists didn’t know how 4VA was produced in the locust’s body—or whether there was a way to interrupt that process.

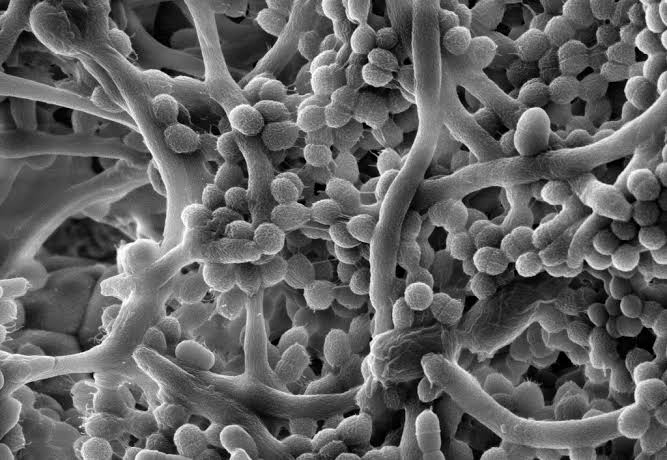

The Chinese research team dove deep into the insect’s biology, zeroing in on the hind legs—the apparent site of 4VA production. There, they began a painstaking process: deactivating genes one by one, searching for the ones responsible for manufacturing this pheromone.

What they found was the molecular key to the locust’s most dangerous secret.

Meet the Enzyme That Unleashes a Swarm

The team identified an enzyme named 4VPMT1 as the critical catalyst in the creation of 4VA. This enzyme transforms a naturally occurring compound in the insect’s body, called 4VP, into the swarming pheromone 4VA.

It’s like flipping a biochemical switch—from peaceful individual to voracious swarm.

Further analysis revealed that this transformation isn’t random. Several other molecules help guide and stabilize the chemical process, making 4VA production an efficient and reliable system. And once one locust starts producing it, others follow. The swarm begins. The damage begins. And it doesn’t stop until the food runs out.

A Synthetic Solution, and Its Drawbacks

Armed with this new knowledge, the researchers didn’t stop at discovery. They turned toward intervention.

They tested a known compound, 4-nitrophenol, feeding it to locusts in small quantities. The results were dramatic: the insects no longer made the switch from solitary to swarming behavior. The compound effectively blocked the chemical pathway that led to 4VA production.

For a moment, it seemed like the solution humanity has sought for millennia might finally be at hand—a way to prevent swarms without using harmful pesticides or killing off entire ecosystems.

But 4-nitrophenol comes with its own cost. It’s toxic, not only to pests but to plants and the environment. Using it on a large scale would trade one ecological problem for another. It’s not the perfect answer. Not yet.

A Path Forward Without Poison

Still, the discovery marks a turning point. For the first time, scientists know how locusts create the chemical that drives their most devastating behavior. And with that knowledge comes the possibility of designing new, more targeted solutions—ones that interrupt the swarm process without poisoning the land or water.

Professor Zhang, one of the lead researchers, described the moment they identified the key enzyme as “both thrilling and sobering.”

“We were excited to find the switch,” he said, “but also aware of the complexity of the problem. It’s not just about stopping locusts—it’s about doing it responsibly.”

The team now plans to test other compounds—ones that can block 4VA synthesis without the harmful effects of 4-nitrophenol. By mimicking parts of the chemical pathway or interfering with the enzyme 4VPMT1, they hope to design a safe deterrent that keeps locusts calm, scattered, and disinterested in destruction.

Reimagining the Future of Pest Control

This study signals more than just a new chapter in locust science—it represents a shift in how we think about pest control. Instead of waging chemical war, researchers are beginning to treat pests as complex biological systems. By understanding the internal mechanics that drive behavior, scientists may be able to guide—or gently disable—those processes before catastrophe strikes.

It’s a move away from brute force and toward biological finesse.

“Locusts don’t want to destroy crops,” noted Dr. Liu, a molecular biologist on the team. “They’re responding to signals. If we change the signals, we change their behavior.”

It’s a powerful idea: not fighting nature, but learning its language.

A New Weapon in an Ancient Battle

Across history, humanity’s struggle with locusts has always been reactive. We wait, we spray, we mourn the losses. But this new research turns the tide. It opens the door to proactive control—to subtle interference in the very signals that summon the swarm.

And while the perfect solution may still be years away, the blueprint is now in place. By unraveling the molecular origins of 4VA, scientists have taken the first step toward a future where locust plagues are no longer feared, but prevented.

As the world grows hungrier and climate change threatens to increase pest outbreaks, discoveries like this don’t just save crops. They secure futures.

The enemy has been named. The signal decoded. The silence before the swarm may, at last, be permanent.

Reference: Xiaojiao Guo et al, Decoding 4-vinylanisole biosynthesis and pivotal enzymes in locusts, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09110-y