Few phrases have stirred as much curiosity, controversy, and confusion as “survival of the fittest.” For more than a century, it has echoed through scientific discussions, political rhetoric, classrooms, and pop culture. At first glance, it seems straightforward: only the strongest survive. But what Darwin actually meant was far more nuanced, deeply rooted in nature’s complexity, and profoundly human in its implications.

The expression was never coined by Charles Darwin. Yet, it became forever linked to his theory of evolution. To understand what Darwin truly meant, and how this phrase has both illuminated and obscured his ideas, we need to journey into the heart of evolutionary theory, Victorian England, and the life of a man who redefined the way we see ourselves in the world.

This is not just a tale of science. It is a story about life, death, adaptation, resilience, and the quiet forces that shape every leaf, lion, and human being.

The Birth of a Revolutionary Idea

When Charles Darwin boarded the HMS Beagle in 1831 as a young naturalist, he could not have imagined the storm he would unleash. For five years, he traveled the world, collecting fossils, studying birds, and observing creatures great and small. From the Galápagos Islands to the coasts of South America, Darwin’s notebooks filled with observations that would later shake the foundations of biology, religion, and human identity.

He returned to England with a growing suspicion that species were not fixed. The variations he saw between similar animals on different islands suggested they had changed over time. But how? What mechanism could drive such change?

Darwin spent the next two decades in near silence, developing his theory in private. He read widely, experimented with pigeons and barnacles, and corresponded with other scientists. What emerged was the theory of natural selection—the idea that individuals with traits better suited to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on those advantageous traits to their offspring.

When Darwin finally published On the Origin of Species in 1859, he offered a compelling and meticulously documented argument for how evolution occurs. But he never used the phrase “survival of the fittest” in that first edition.

Herbert Spencer and the Power of a Catchphrase

The term “survival of the fittest” was actually coined by philosopher Herbert Spencer, who was deeply influenced by Darwin’s work. Spencer first used the phrase in 1864, in his book Principles of Biology, as a way to describe the mechanism of natural selection. To Spencer, it was an elegant summary: those best adapted to their environment survive, and those that are not, perish.

Darwin himself found the phrase useful—eventually. In the fifth edition of On the Origin of Species, published in 1869, he introduced Spencer’s phrase as an alternative to “natural selection,” writing that it was “more accurate, and is sometimes equally convenient.”

But this decision had unintended consequences.

Where Darwin’s language was careful and cautious, Spencer’s phrase was bold and simplistic. It quickly took on a life of its own, interpreted through the lens of Victorian values—where “fitness” was conflated with strength, superiority, and domination. In the hands of social theorists, politicians, and imperialists, “survival of the fittest” became a justification for inequality, colonization, racism, and capitalism.

Darwin never meant it that way.

What Darwin Actually Meant by “Fitness”

To understand Darwin’s concept of fitness, we must let go of modern ideas about muscular strength or moral worth. In evolutionary biology, “fitness” simply means reproductive success: the ability to survive long enough to pass your genes to the next generation.

Fitness is not about being the biggest or the strongest. It’s about being well-suited—well fitted—to a particular environment.

A cheetah is fast because it needs to catch prey. A giraffe’s long neck helps it reach leaves high in the trees. A cactus stores water because it lives in a desert. In each case, the trait improves the chances of surviving and reproducing in a specific context. That is fitness.

In fact, sometimes, cooperation, camouflage, or even smallness can be more “fit” than aggression or size. Evolution has no ultimate goal, no direction, no blueprint. It only favors traits that, in a given moment and place, give an edge in reproduction.

And here lies the deeper truth Darwin tried to reveal: fitness is always relative. What works in one environment may be useless—or even dangerous—in another.

Nature’s Quiet Tinkerer

Evolution, as Darwin saw it, is not a race where the strongest wins. It is a slow, almost invisible process of trial and error, where every organism is a kind of experiment.

Natural selection is not a designer. It is a filter. It does not create perfect beings—it weeds out the combinations of traits that don’t work as well as others. Sometimes, traits that seem useless—like the human appendix—persist simply because they don’t get in the way of survival.

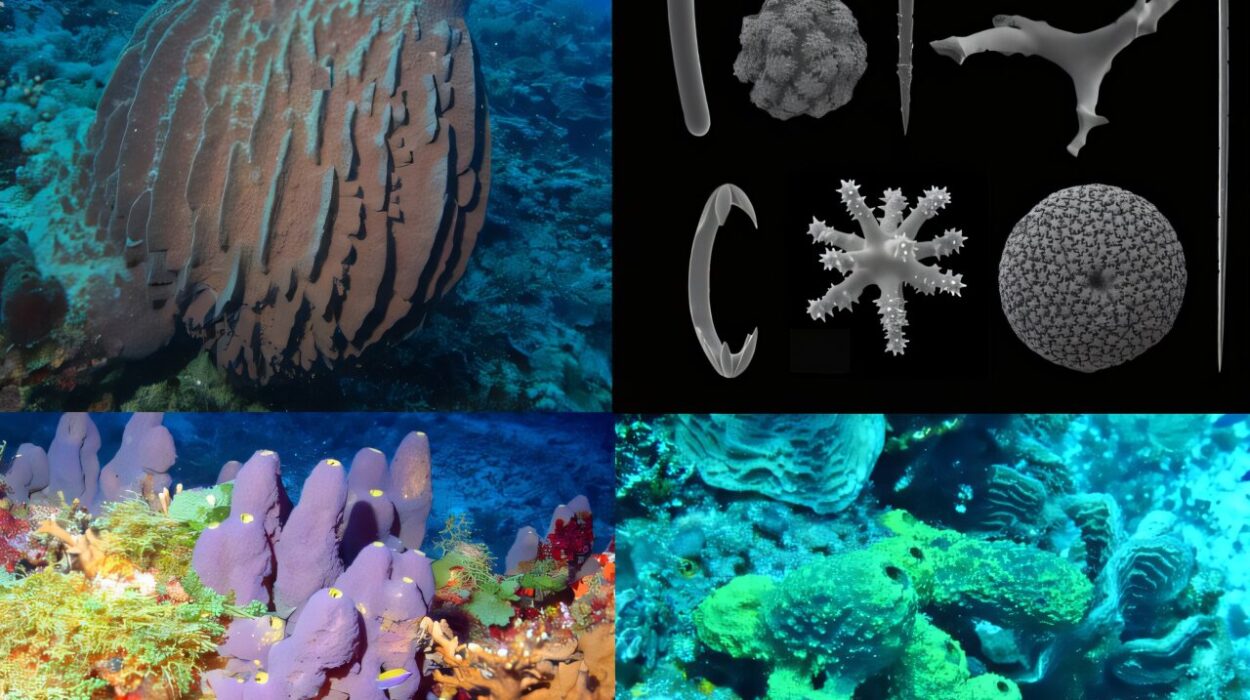

And evolution does not favor complexity for its own sake. Some of the most successful organisms on Earth are bacteria, which have remained largely unchanged for billions of years. Their simplicity is their strength.

This subtle, tinkering process shapes every living thing over generations. It does not care for fairness. It does not reward effort. It is blind, patient, and ruthlessly efficient.

But it is also beautiful. Because from this unfeeling process comes the full splendor of life on Earth—from the peacock’s feathers to the orchid’s bloom to the human brain.

Misusing Darwin: The Rise of Social Darwinism

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Darwin’s ideas were twisted to fit dangerous ideologies. Thinkers like Herbert Spencer and others in the social sciences began applying “survival of the fittest” to human societies.

They argued that poverty, illness, or social failure were signs of unfitness—and that helping the weak was interfering with natural selection. This was the birth of Social Darwinism.

It became a tool for justifying economic inequality, colonialism, and even genocide. The Nazis took these ideas to horrific extremes, embracing a twisted vision of biological purity and eugenics, claiming they were acting in accordance with nature.

Darwin himself would have been horrified. He was a gentle, morally driven man who abhorred slavery, cruelty, and violence. He believed in compassion, not conquest. His science was descriptive, not prescriptive. He observed what happened in nature—he did not suggest how humans ought to behave.

The confusion between scientific explanation and moral justification remains one of the greatest misinterpretations of his work.

Cooperation and the New View of Fitness

Modern evolutionary biology has dramatically reshaped our understanding of “fitness.” It turns out that cooperation is not only common in nature—it is often essential.

From bees that sacrifice their lives for the hive to cleaner fish that eat parasites off larger fish, mutual benefit abounds. Even inside your own body, mitochondria—tiny energy-producing organelles—were once free-living bacteria that merged with our cells in a symbiotic relationship.

Kin selection, group selection, and reciprocal altruism are all concepts that have emerged to explain why helping others—especially relatives or members of a community—can increase genetic success.

In humans, cooperation and empathy are among our greatest survival traits. We form families, tribes, cities, nations. We build hospitals, share food, and teach our children. These behaviors may seem “un-Darwinian” if you believe fitness is only about competition. But in fact, they reflect a deeper truth: that evolution often favors the ability to work together.

Darwin himself recognized this. In his later work The Descent of Man, he wrote: “Those communities which included the greatest number of the most sympathetic members would flourish best and rear the greatest number of offspring.”

In other words, kindness can be a form of fitness.

Evolution Is Not a Ladder

One of the most enduring myths of evolution is that it moves toward higher forms—that humans are its pinnacle, and all other creatures are lower steps on a ladder.

Darwin rejected this idea. Evolution is not a ladder. It is a branching tree, with every species adapted to its own niche. Bacteria are not “less evolved” than birds. They are simply differently evolved. Every living organism today is the product of an unbroken line of survivors stretching back billions of years.

The idea of “superior” species or “higher” races is not only scientifically false—it is morally bankrupt. Evolution does not assign value. It only describes success in reproductive terms.

Understanding this helps us see the world more clearly—and with greater humility. We are not the center of creation. We are one branch among many.

Darwin’s Enduring Relevance

Charles Darwin died in 1882, but his ideas have only grown more powerful with time. The discovery of DNA, the explosion of genetic research, and the mapping of genomes have confirmed and deepened the insights he offered with nothing more than notebooks, fossils, and patience.

Today, evolutionary theory is the foundation of modern biology. It explains the spread of antibiotic resistance, the development of new species, the patterns of migration, and the shared ancestry of all life.

Yet the phrase “survival of the fittest” continues to haunt the conversation. It’s often misquoted, misunderstood, and misapplied. That’s why it’s so important to revisit what Darwin really meant.

Fitness is not a contest of brutality. It is a dance between organism and environment. It is flexibility, not force. Adaptation, not aggression. Cooperation, not cruelty.

It is not about the survival of the strongest, but the survival of those who fit best—who bend without breaking, who change without losing their essence, who find harmony with the world around them.

What It Means to Be Fit Today

In the modern world, “fitness” takes on new meanings. We live in cities, surrounded not by predators, but by technology. Our challenges are no longer about finding food or escaping lions, but managing stress, raising children, navigating social networks, and preserving the planet.

And here, too, evolution has something to teach us.

The traits that help us thrive today may be emotional intelligence, adaptability, creativity, and empathy. The ability to work in teams, to handle complexity, to care for others—these are the new frontiers of fitness.

Even as climate change, pandemics, and social unrest threaten our survival, the lessons of evolution remind us that we can endure—not by domination, but by adaptation.

We are the only species that can reflect on evolution. That can study it, understand it, and shape our own future based on its insights. That is both our burden and our gift.

Conclusion: Darwin’s Quiet Revolution

When Charles Darwin introduced the world to natural selection, he did not scream or boast. He whispered. He offered a slow, careful, revolutionary idea: that life changes. That it changes not by design, but by consequence. That beauty and complexity arise not from intention, but from survival.

And he showed us that survival does not belong to the strongest. It belongs to the most attuned, the most responsive, the most connected to the world they inhabit.

“Survival of the fittest” is not a call to cruelty. It is a reminder that life is not static, that we are all part of a grand, unfolding experiment. And in that experiment, the fittest may not be the ones who conquer, but the ones who care, who cooperate, who evolve with grace.

Darwin taught us that we are not separate from nature—we are shaped by it, and shaping it in return. And that understanding may be the most powerful survival trait of all.