Imagine standing in a vast forest, sunlight filtering through the trees, the air alive with birdsong and the rustle of unseen creatures. You are surrounded by life in every direction—moss clinging to bark, ants marching in single file, birds flitting from branch to branch. And hidden in all this wonder is a quiet, patient force—one so powerful it has shaped the colors of those birds’ feathers, the way the ants navigate, the very design of the wings in flight.

This force is not magic, nor chaos. It is natural selection—one of the most important ideas in all of science. Though it moves too slowly to witness in a single heartbeat, it is relentless and breathtaking in its consequences. Through it, life has transformed from simple cells in ancient oceans into the majestic and diverse world we now inhabit.

To understand natural selection is to glimpse the mechanism behind evolution, the deep engine of change that has sculpted life over billions of years. But don’t be intimidated. Natural selection, at its core, is simple. Not easy—but simple. And it tells a story more profound than any legend.

The Man Who Dared to Ask Why

Natural selection is often linked to one name: Charles Darwin. But he wasn’t the first to wonder how life came to be so diverse. For centuries, people looked at the natural world and asked questions—why do giraffes have long necks? Why do birds come in so many shapes? Why do some animals disappear forever while others thrive?

In the 1800s, the dominant belief in Europe was that every species had been created exactly as it was, fixed and unchanging, by a divine power. But Darwin, a young Englishman with a love for nature, couldn’t ignore the clues all around him—fossils of extinct creatures buried beneath modern layers of rock, animals on different islands that seemed strangely similar yet distinct, and the incredible variation he observed during his voyage on the HMS Beagle.

It wasn’t a sudden revelation. It was slow, painstaking observation and relentless thinking that led Darwin to his idea. He realized something extraordinary: species weren’t fixed. They changed, gradually, over time. And the driving force behind that change was not random—it was selection, a natural process that favored some traits over others, depending on the environment.

Darwin published his theory in 1859 in his revolutionary book, On the Origin of Species. And though it caused controversy, it also opened the floodgates of understanding. Since then, natural selection has become the backbone of modern biology. But its core idea is still beautifully simple.

The Basics: Survival and Reproduction

At the heart of natural selection is a basic truth: not all individuals survive, and not all those who survive reproduce equally. Life is full of competition—for food, space, safety, and mates. In every generation, more organisms are born than the environment can support. Some will be slightly better suited to the struggle than others. They will survive just a bit longer, find more food, escape predators more often, and perhaps produce more offspring.

Those slight advantages matter. If those individuals pass on their traits to the next generation, and those traits help their offspring too, then over time, those traits will become more common. This is the essence of natural selection.

Imagine a population of beetles. Some are green, some are brown. In a forest with dark soil, birds more easily spot the green beetles and eat them. The brown beetles are harder to see—they survive better. They reproduce, passing on their brown color to more beetles. Over many generations, the population shifts to mostly brown beetles. That’s natural selection in action.

It’s not about strength or intelligence or “deserving” to live. It’s about what works—what helps an organism survive and reproduce in a particular place and time. Nature is not kind or cruel. It selects what fits.

Variation: The Raw Material of Evolution

For natural selection to work, there must be variation—differences between individuals in a population. Without variation, selection has nothing to act on. This variation comes from multiple sources: mutations in DNA, the mixing of genes during reproduction, and the reshuffling of genes when cells divide.

Mutations, though often thought of negatively, are the wellspring of new traits. Most mutations are neutral, some are harmful, but a few are beneficial. A single mutation can lead to a slightly longer beak, a thicker fur coat, or the ability to digest a new type of food. Over time, these small changes can build into big differences.

Imagine a pack of wolves living in a cold climate. A mutation leads one pup to grow slightly thicker fur. It survives harsh winters better than its siblings. If this thicker coat gives it even a slight advantage in survival and mating, its offspring may inherit the trait. Multiply this by generations, and the whole pack may become more insulated against the cold.

Variation is not optional. It’s essential. And it’s why every species has potential to change over time—because no two individuals are exactly alike, and in a changing world, some differences can mean the difference between life and death.

Environment: The Ever-Shifting Stage

Natural selection doesn’t act in a vacuum. It always plays out on the stage of the environment—and that stage is always shifting. A trait that helps in one context might be useless or even harmful in another.

Take the polar bear, whose white fur helps it blend into snowy landscapes. But if the climate warms, the ice melts, and forests take over, that camouflage becomes a liability. Or consider antibiotic resistance in bacteria: in the presence of antibiotics, resistant strains thrive. In their absence, those same mutations can be costly.

Environments aren’t just physical—temperature, rainfall, terrain—they’re also biological. The presence of predators, prey, parasites, or competitors can all shape what traits are favored. And because other species are evolving too, natural selection is often a race. This ongoing evolutionary arms race is known as coevolution, and it’s seen in everything from cheetahs and gazelles to viruses and immune systems.

Natural selection is not about progress toward perfection. There is no master plan, no final destination. There is only adaptation to current conditions. If the conditions change, the direction of selection can change too.

Time: The Patience of the Earth

One of the hardest parts of understanding natural selection is grasping its timescale. We are used to change happening quickly. But evolution moves slowly, over thousands or millions of years. It’s not visible in a single lifetime. But given enough time, it can transform tiny changes into entirely new species.

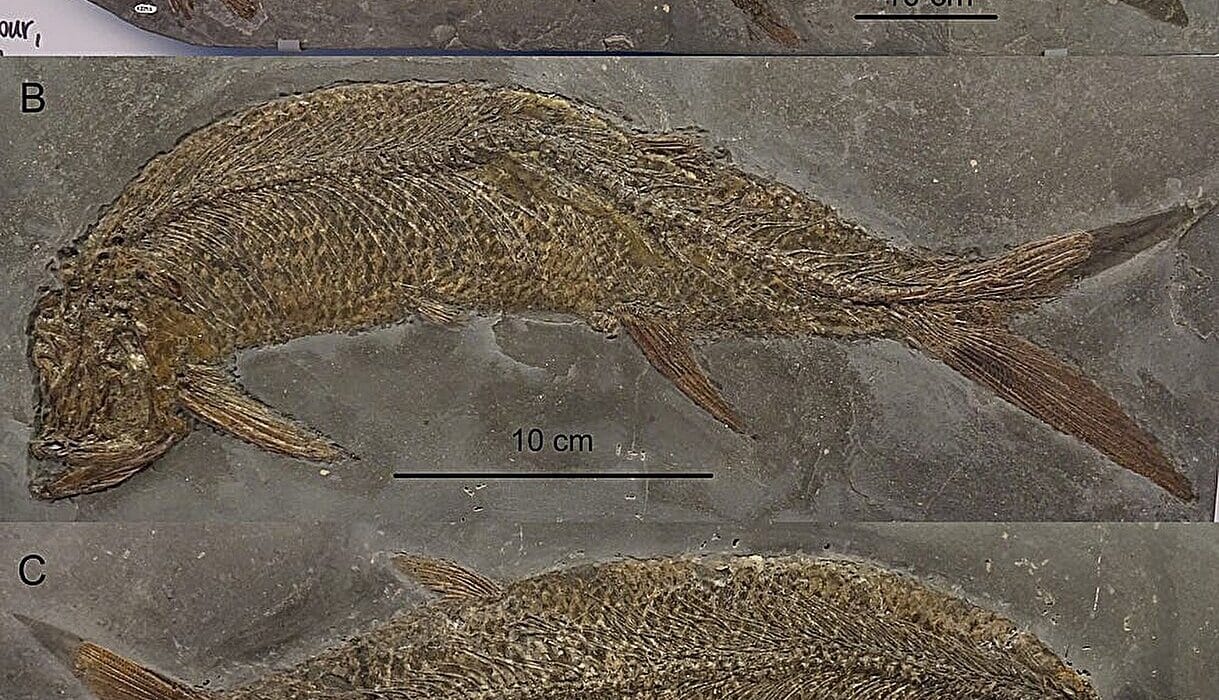

This is why fossils are so important. They offer snapshots of past life and allow us to trace how organisms have changed. The fossil record shows ancient creatures that no longer exist—giant sloths, trilobites, saber-toothed cats. It also shows transitions—fish with the beginnings of limbs, reptiles with feathers, early humans walking upright.

We also see natural selection at work today, especially in fast-reproducing organisms like bacteria or insects. Antibiotic resistance, pesticide resistance, and rapidly evolving viruses like influenza or HIV offer dramatic, real-time examples of how selection operates.

But the grandest changes—the evolution of eyes, wings, lungs, and brains—are written in the deep history of life. They are stories that unfold over vast spans of time, through millions of tiny steps. And yet, each step is governed by the same simple rule: what works survives.

Misunderstandings: What Natural Selection Is Not

Natural selection is powerful, but often misunderstood. One common misconception is that it’s “just a theory,” as if it were a guess. In science, a theory is not a hunch—it’s a comprehensive explanation supported by mountains of evidence. Like the theory of gravity or the theory of relativity, the theory of evolution by natural selection is one of the best-supported ideas in all of science.

Another myth is that natural selection is about individuals adapting within their lifetime. But evolution doesn’t happen to individuals—it happens to populations over generations. A rabbit doesn’t grow longer ears because it hears danger better. But if rabbits with longer ears survive more often and reproduce more, their genes become more common in the population.

Natural selection also isn’t about perfection. Organisms are not evolving toward some ideal form. Evolution works with what it has, making the best of existing structures. That’s why the human eye has a blind spot, or why whales still have tiny bones in their bodies that once supported legs.

And natural selection doesn’t imply that life is meaningless or directionless. It reveals how deeply connected we are to every other form of life on Earth. We are not separate from nature—we are products of it, shaped by the same forces that sculpted every creature in the forest, every fish in the sea, every bird in the sky.

The Evidence: Watching Nature’s Sculptor at Work

Natural selection isn’t just a beautiful idea—it’s backed by overwhelming evidence. We see it in fossils, in genes, in embryos, in the distribution of species across the globe. We see it in experiments, in labs and in nature.

The peppered moth in England is a classic example. Before the Industrial Revolution, most were light-colored, blending in with lichen-covered trees. As soot blackened the trees, darker moths became more common, because they were harder for birds to spot. When pollution decreased, the lighter forms returned. That’s natural selection responding to a changing environment.

In agriculture, we’ve seen how pests evolve resistance to pesticides in just a few years. In medicine, we fight bacteria that evolve resistance to drugs, requiring constant innovation.

And in our own bodies, we see remnants of evolution—vestigial organs, shared genes with distant relatives, and patterns of development that trace our ancestry.

Each line of evidence points to the same conclusion: natural selection is not hypothetical. It is a real, observable force that explains not only how life has changed, but why it continues to change.

A Deeper Meaning: Our Place in the Great Tapestry

Understanding natural selection doesn’t diminish life—it enriches it. It invites us to see the beauty in the ordinary and the miraculous in the mundane. A hummingbird’s wings, a spider’s web, a child’s eye color—all carry within them the fingerprints of natural selection.

It also reminds us of our shared ancestry. Humans are not separate from animals; we are animals. We are part of a lineage that goes back unbroken for billions of years. Every one of our ancestors—single-celled, finned, furred—survived long enough to reproduce. Every link in the chain was tested by nature. And here we are.

This perspective fosters humility, but also awe. We are not the center of the universe, but we are its witness. We are nature becoming aware of itself.

And with that awareness comes responsibility. Because though natural selection is blind and impartial, we are not. We have the power to shape our future—to preserve biodiversity, to combat disease, to care for the planet that shaped us.

The Endless Journey of Life

Natural selection doesn’t end. It continues, quietly, everywhere. In the rustling grasslands, in the depths of the ocean, in the city streets, even in our bodies. Every species alive today is the result of a long history of selection, survival, and change.

And the journey continues. As climates shift, as habitats shrink, as diseases spread, life is constantly tested. Some species will adapt, others will vanish. New forms will emerge. The story is far from over.

We are not spectators. We are part of this story. Our choices—what we protect, what we destroy, what we value—will shape the evolutionary path not only of other species, but of our own.

Natural selection has no purpose, no foresight. But we do. And that gives us a unique role—not to control nature, but to understand it, and to live in harmony with its deep, slow wisdom.