In a remote corner of the Baltic Sea, on the tiny island of Stora Karlsö, researchers have uncovered a stunning surprise—a discovery that challenges everything we thought we knew about the ancient relationship between humans and wolves. The remains of two wolves, aged between 3,000 and 5,000 years, were found in the Stora Förvar cave, a site that had long been associated with prehistoric seal hunters and fishers. What makes this discovery so extraordinary is not just the age of the wolves, but the fact that they were found on an island with no native land mammals. The only way they could have arrived there is by human hands.

The small island, which stretches only 2.5 square kilometers, offers a unique window into a time long past—a time when the dynamics between humans and wild animals were far more complex than we once imagined. The presence of these wolves, brought deliberately by people to this isolated environment, opens up new possibilities for understanding how our ancestors interacted with the animals they lived alongside.

Wolves Living Among Humans

The remains of these wolves, after careful analysis, revealed something truly remarkable. Despite being located in a place far from their natural range, the wolves were not wild dogs. Genomic testing confirmed that they were true gray wolves, with no trace of dog ancestry. Yet, they exhibited traits that are typically associated with a life in close proximity to humans. Their bones revealed a diet rich in marine proteins—seals and fish—much like the humans who lived on the island at the time. This suggests that these wolves were likely being fed by the people living there, rather than hunting for themselves.

Dr. Linus Girdland-Flink, one of the lead researchers from the University of Aberdeen, was struck by the implications of this discovery. “The discovery of these wolves on a remote island is completely unexpected,” he said. “Not only did they have ancestry indistinguishable from other Eurasian wolves, but they seemed to be living alongside humans, eating their food, and in a place they could have only have reached by boat. This paints a complex picture of the relationship between humans and wolves in the past.”

This unexpected find challenges the traditional view of early human-wolf interactions. Most of us have been taught to think of wolves as wild animals, feared or revered, but rarely as companions or controlled creatures. However, the evidence points to a far more intricate relationship, suggesting that in some cases, humans may have deliberately interacted with wolves in ways that went beyond simple hunting or avoidance.

The Mystery of the Wolves’ Isolation

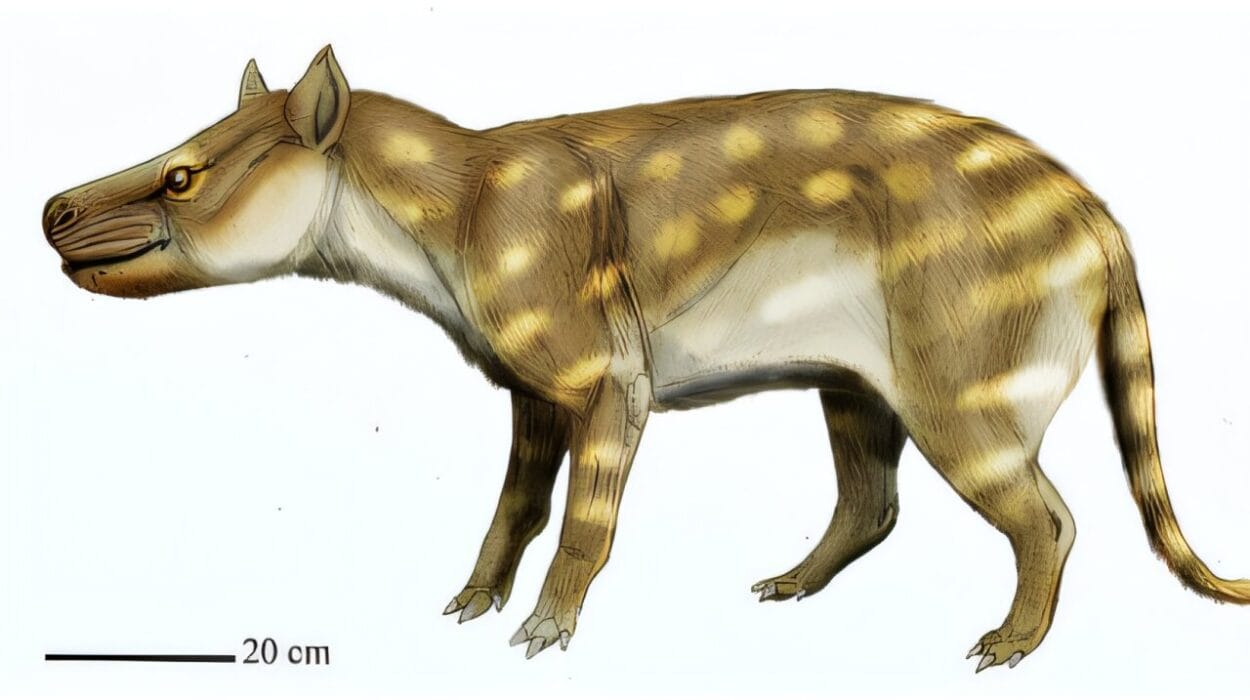

What makes the Stora Karlsö wolves even more intriguing is their size and genetic makeup. Unlike the larger wolves typically found on the mainland, these wolves were noticeably smaller, perhaps a sign of selective breeding or isolation. One of the wolves also displayed signs of low genetic diversity, a trait often linked to isolated populations or domesticated animals. According to Anders Bergström from the University of East Anglia, this is a particularly telling piece of evidence. “The genetic data is fascinating,” he explained. “We found that the wolf with the most complete genome had low genetic diversity, lower than any other ancient wolf we’ve seen. This is similar to what you see in isolated or bottlenecked populations, or in domesticated organisms.”

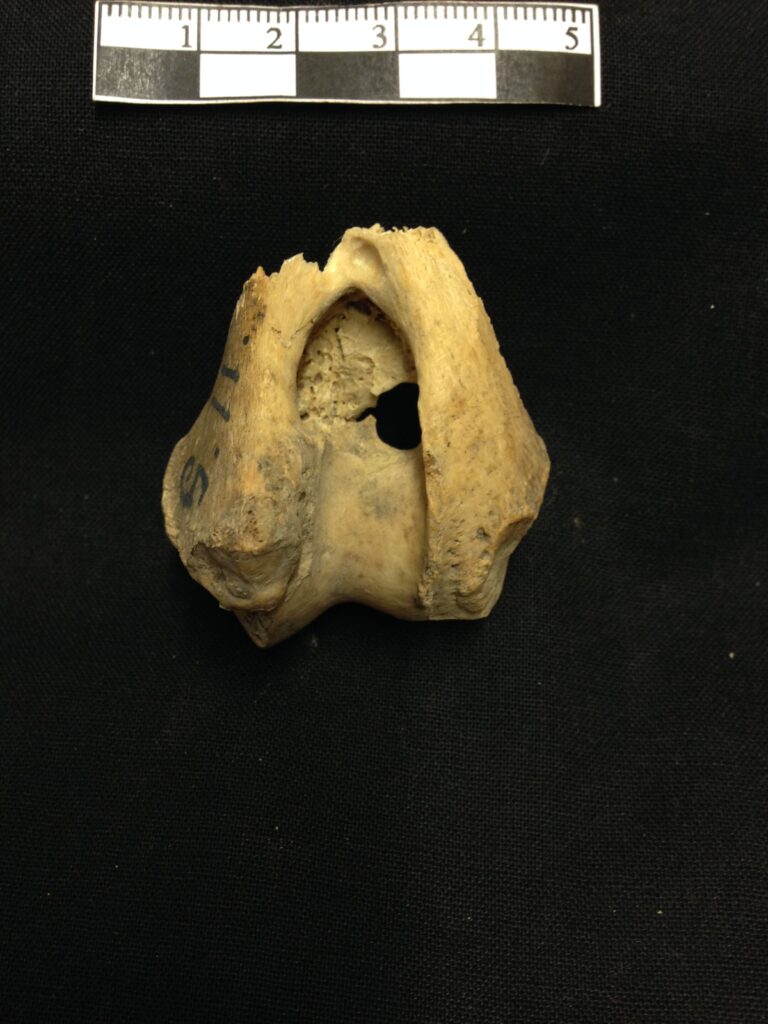

While it’s still not clear whether these wolves were tamed, kept in captivity, or managed in some other way, the combination of genetic findings and their physical characteristics suggests that humans were involved in their care. One wolf even exhibited advanced pathology in its limb bone, indicating it may have had difficulty moving. This could have been a result of injury or illness, but its survival in an environment where it would not have had access to large prey raises the possibility that it was being nurtured by the humans on the island.

Pontus Skoglund, a senior author of the study from the Francis Crick Institute, was equally surprised by the implications of the findings. “It was a complete surprise to see that it was a wolf and not a dog,” he said. “This is a provocative case that raises the possibility that in certain environments, humans were able to keep wolves in their settlements, and found value in doing so.”

Rethinking the Role of Wolves in Human History

The discovery of these isolated wolves offers a tantalizing glimpse into a time when the relationship between humans and the wild was more fluid, more complex, and perhaps more intentional than we ever thought. While the domestication of dogs has long been understood as a gradual process that likely began around 15,000 years ago, this new evidence suggests that earlier interactions with wolves may have been more direct and managed in some cases. These wolves may not have been the first steps toward domestication, but they could represent a form of human-wolf cooperation that was different from the dog domestication we’re familiar with.

The study’s co-lead author, Jan Storå, Professor of Osteoarchaeology at Stockholm University, emphasized the importance of combining genetic and physical evidence in this kind of research. “The combination of data has revealed new and very unexpected perspectives on Stone Age and Bronze Age human-animal interactions in general and specifically concerning wolves and also dogs,” he said. “These findings suggest that the ways in which early humans interacted with wolves may have been more diverse than previously thought.”

This new understanding of prehistoric human-animal interactions forces us to reconsider our assumptions about domestication and the roles wild animals played in ancient societies. Were these wolves companions, guardians, or simply useful animals that served a purpose beyond hunting? Perhaps these ancient humans saw something in wolves—something that we’re only beginning to understand.

Why This Research Matters

The discovery of these ancient wolves forces us to reimagine the early chapters of human history, particularly the ways in which we engaged with the natural world. It challenges the conventional view of wolf-human interactions, suggesting that they may have been more complex and cooperative than we once believed. If humans were indeed managing wolves in some capacity thousands of years ago, it could indicate that our relationship with animals was already evolving in ways that would eventually lead to the domestication of dogs.

This research also highlights the power of combining modern genetic tools with physical evidence to unearth stories that have been buried for millennia. By piecing together the bones, genomes, and isotopic data, scientists are revealing the hidden histories of our ancestors and their animal companions. It’s a reminder that the past is never as simple as we imagine, and that every discovery opens the door to new mysteries waiting to be uncovered.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond the Baltic Sea. They offer a glimpse into the early, perhaps unexpected, ways humans shaped their world, influencing the animals around them in ways that were not always documented in written history. As researchers continue to analyze ancient remains, who knows what other surprises they may uncover about the creatures that once roamed alongside our ancestors.

More information: Girdland-Flink, Linus et al, Gray wolves in an anthropogenic context on a small island in prehistoric Scandinavia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2421759122. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2421759122