For more than a century, a small mystery slept in museum drawers and private collections. Three fragmentary remains of a Jurassic fish, thought to belong to a species called Seminotus manselii, waited without fanfare for someone to return to them with fresh eyes. They traveled from Wareham to London, passing through the hands of Lord Enniskillen and Lord Egerton, gathering dust as new discoveries eclipsed the old. And yet, hidden in those fragments was the shadow of a creature whose true identity had never been fully understood.

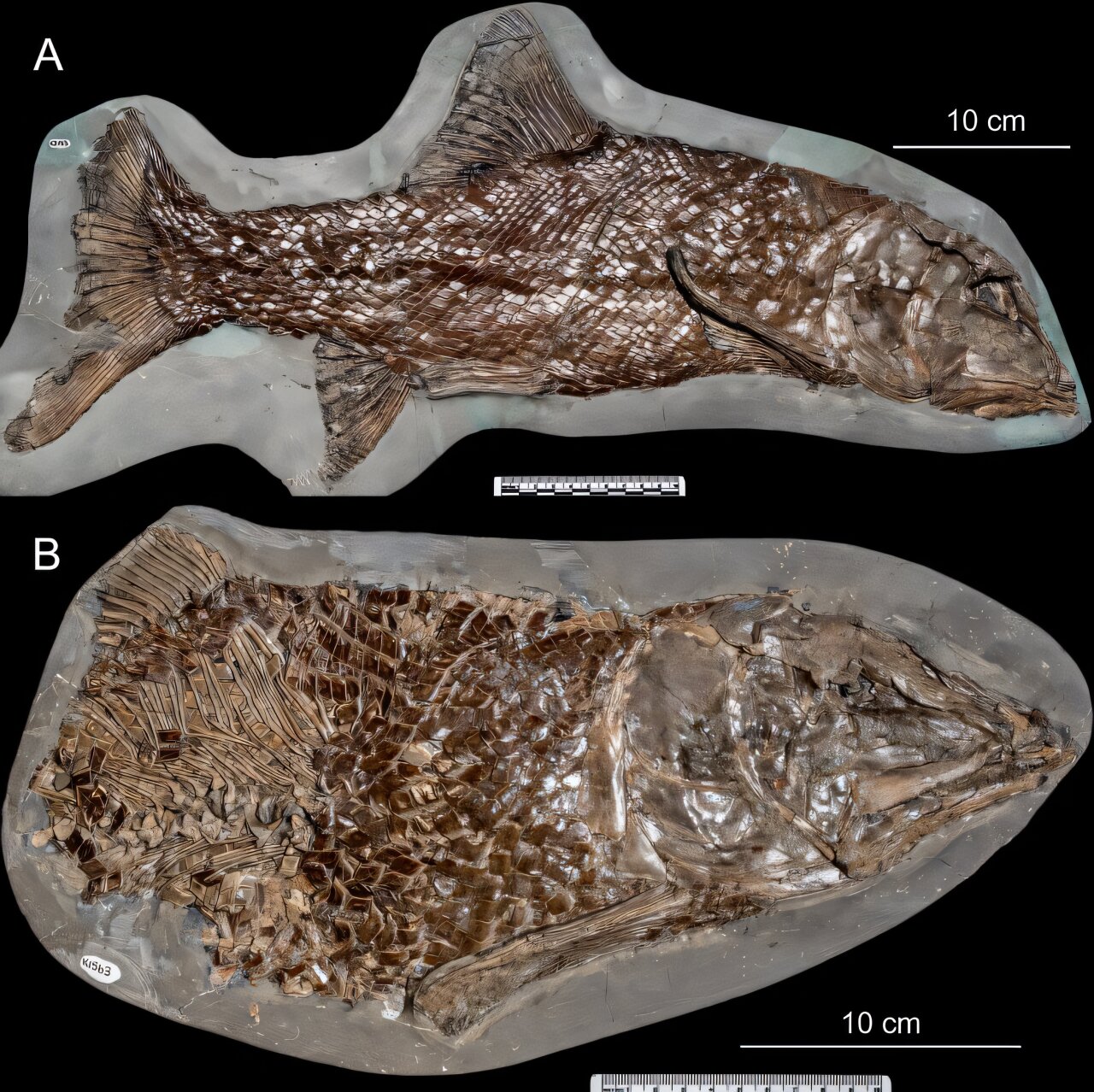

That quiet story changed when a single, beautifully complete fossil emerged from the Kimmeridge Clay of southern England—an exquisitely preserved specimen collected by Dr. Steve Etches, a fossil hunter who has spent decades combing the Jurassic seabed locked inside stone. This specimen would become the beating heart of a scientific detective story, one that finally allowed researchers to reconstruct a fish that lived nearly 155 million years ago.

“Collections worldwide possess numerous exciting fossils. Some even represent thus far unknown species. Others are superbly preserved specimens of species that have been described a long time ago using fragmentary and less well-preserved individuals,” explains Dr. Martin Ebert of Ludwig Maximilian University Munich. His words echo the challenge at the core of paleontology: the past does not always reveal itself willingly, and sometimes its truths must be chased.

Rediscovering a Species Lost in Plain Sight

The key to solving the mystery of Brachyichthys manselii lay not only in the new fossil, but also in the dusty trail of old descriptions—brief, incomplete, and sometimes accompanied by poor illustrations. For Dr. Ebert, tackling this historical tangle required patience and what he describes as a form of scientific sleuthing.

“When doing taxonomic work, i.e., identifying fossils and describing them in great detail, it is important to carefully examine previously described type specimens to determine whether the fossil in question represents a new species or one that has already been described.”

But those early holotypes, he notes, are often elusive. “Many older type specimens, however, were only very briefly described, have poor figures, or their whereabouts are unknown. Therefore, it often takes detective work to find out where these specimens are located in order to study them and to compare them with newer, well-preserved specimens that offer new insights into the anatomy of the species.”

The detective work paid off. With the new fossil in hand—complete, clear, and meticulously prepared—Ebert and Etches realized that the old fragments did not belong to Seminotus at all. They instead represented a distinct species whose true form could only now be seen for the first time.

A Fossil Donated, a Species Revealed

The moment of revelation was made possible because in 2015, Dr. Etches donated his entire fossil collection to The Kimmeridge Trust, ensuring its preservation and scientific study. Among hundreds of specimens was the extraordinary fish that would rewrite the story of B. manselii. This was no shattered relic but an anatomically complete predator, its bones arranged as they had been in life, its features intact enough to trace the arc of its evolution.

Measuring approximately sixty-two centimeters, the fish cuts an elegant figure even after millions of years. Long and robust, covered in thick diamond-shaped ganoin scales arranged in about forty-five rows, it carried itself through Jurassic waters with a peculiar mix of strength and sensitivity. Its upper jaw held between fifty and sixty slender teeth—small but numerous, hinting at a diet of swift and slippery prey.

One detail stands out in particular: the lateral line, a sensory system that detects movement in the water, did something unusual. Instead of ending before the tail, as in many fish, it continued all the way into the fin, mirroring the pattern found in a few other Jurassic Ophiopsiformes. For the researchers, this feature helped anchor the species more firmly within its evolutionary lineage.

And there was another clue in its tail. With twenty-eight principal caudal fin rays, the tail fin held more rays than many of its relatives, a distinctive anatomical signature that helped refine its place within the Halecomorphi, a once-diverse group now represented only by two “living fossil” bowfin species in North America.

A Window Into Jurassic Waters

Armed with a clear understanding of B. manselii’s form, Ebert and Etches widened their scope. They examined 212 fish specimens from the Etches Collection to determine how this species fit within the ancient ecosystem. Their findings revealed a vibrant underwater world. Teleosts—the ancestors of most modern bony fishes—dominated the fauna at seventy-two percent. Halecomorphi, including B. manselii, accounted for about eleven percent.

The discovery enriched more than taxonomy. It illuminated a lost era of extraordinary fish diversity. “The detailed description of B. manselii provides a crucial step in better understanding the evolutionary history of Halecomorphi and provides new insights into the osteology and systematic position of B. manselii.”

Dr. Ebert reflects on this vanished world with something like awe. “Not only were the Ophiopsiformes diverse … but also the Amiiformes, Pycnodontiformes, Ginglymodi, Teleosteomorpha, and Teleostei. They all have diversified in various ecological niches. In contrast, today, bony fish diversity is almost exclusively limited to the Teleostei, which no longer look as uniform as they did in the Jurassic, whereas many of the Jurassic groups (Ophiopsiformes, Pycnodontiformes, Teleosteomorpha) are now extinct.”

The ghostly variety of Jurassic seas has dwindled, but through fossils like this one, its story returns to the surface.

Why This Discovery Matters

To resurrect the identity of Brachyichthys manselii is not merely to name a fish. It is to restore a lost thread in the tapestry of life’s history. With one complete fossil, scientists can now see the full anatomy of a creature previously known only from fragments. They can trace its lineage, understand its adaptations, and situate it among the cast of ancient marine species that once thrived in European waters.

The work also underscores the profound importance of museum collections—those vast, quiet vaults of deep time. Hidden within them are species awaiting rediscovery, stories half-told, and data that can transform understanding when paired with new material. Each fossil is a puzzle piece, and sometimes the key to solving it lies in donations, revisited archives, or the persistence of researchers willing to track down specimens lost to history.

This research matters because it deepens our grasp of evolution, revealing how life forms once flourished and vanished, how groups rose and fell, and how today’s biodiversity was shaped by ancient events. By reconstructing a long-extinct predator with fresh precision, the study of B. manselii strengthens the bridge between past and present, reminding us that every new fossil—every silent stone—may hold the next breakthrough waiting to be uncovered.

More information: Martin Ebert et al, New description of Brachyichthys manselii (Egerton, 1872) comb. nov. (Neopterygii: Halecomorphi) from the Upper Jurassic of Kimmeridge, England, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2025). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf119