Stonehenge, the prehistoric crown jewel of Britain, is known worldwide for its monumental sarsen stones—colossal, sun-drenched giants standing in somber, sacred silence. Yet behind the awe-inspiring spectacle of these towering sentinels lies a deeper, subtler puzzle—one wrapped not in grandeur but in a modest, blue-hued fragment no bigger than a shoebox. The Newall boulder, often overlooked in the story of Stonehenge, has quietly become a central figure in one of archaeology’s most enduring debates: were the smaller bluestones of Stonehenge brought by the determined will of Neolithic people or by the slow, grinding movement of ancient glaciers?

For decades, this mystery has split scientific opinion. The Newall boulder, however, may have finally tipped the scale—and what it reveals is as much a triumph of human ingenuity as it is a resurrection of forgotten effort from the deep past.

A Fragment with a Secret

Unearthed nearly a century ago during a 1924 excavation at Stonehenge led by Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley, the Newall boulder wasn’t much to look at. Measuring just 22 × 15 × 10 centimeters, it might have been dismissed as an ordinary rock if not for the attention it received from R.S. Newall, a geologist who took it into his private collection, along with seventeen other specimens. The boulder quietly journeyed through time—examined, sliced into thin sections, and stored in institutions such as the British Geological Survey and Amgueddfa Cymru (Museum Wales).

But for all its years in quiet captivity, the Newall boulder held on to its secret: where it had come from, and how it had arrived in the middle of Salisbury Plain, far from any natural deposit of its kind.

Some scholars believed it to be a relic of glacial transport—a stone accidentally delivered to the site by ice sheets long before humans walked those windswept fields. Others argued it was a broken remnant of one of the famed Stonehenge bluestones, deliberately dragged, hauled, and honored by Neolithic builders from the Preseli hills of Wales, over 200 kilometers away.

This disagreement made the Newall boulder a touchstone of a larger controversy. And in a new study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, the mystery may now be solved.

Unearthing the Truth, One Grain at a Time

Led by researchers at Aberystwyth University, the investigation into the Newall boulder went far beyond surface appearances. The team conducted detailed mineralogical, petrographic, and geochemical analyses—using modern scientific tools to unlock ancient geological truths buried within the stone’s microscopic structure.

The results were stunning. The boulder was found to precisely match the Rhyolite Group C from Craig Rhos-y-Felin in northeast Pembrokeshire, Wales—a site already identified as the source of some of the standing bluestones at Stonehenge. The match wasn’t just suggestive—it was compelling. Thin-section analysis revealed a texture and mineral fingerprint that could not have been random. Geochemical data further confirmed that the Newall boulder shared the unique signature of rocks quarried from Craig Rhos-y-Felin.

But origin was only part of the equation. The method of the stone’s arrival—whether by nature or human hand—was the heart of the debate.

Absence of Ice, Presence of Purpose

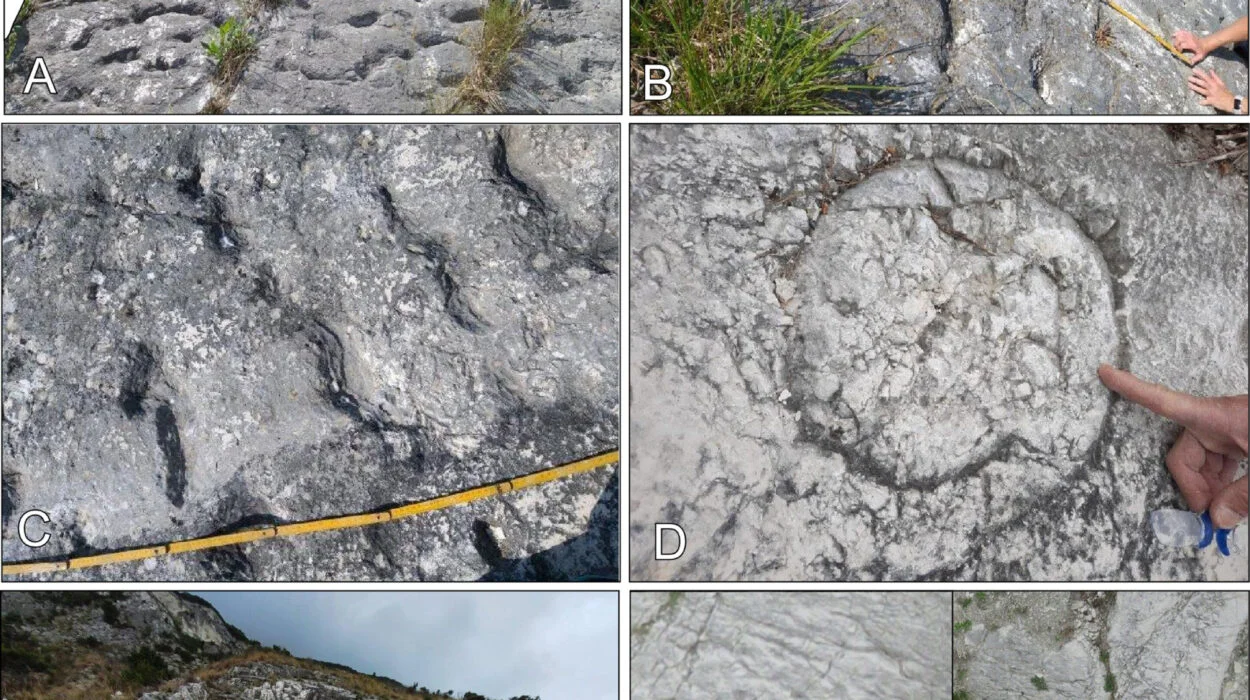

One of the strongest arguments for glacial transport had been the idea that ice, not humans, could have carried the boulders down from Wales during a prehistoric glacial advance. Yet the new research sharply undercuts this possibility. The surface of the Newall boulder bore no signs of glacial striations—those telltale scars of ice dragging stone across stone. Instead, the surface abrasion could be attributed to ordinary weathering and post-breakage burial.

Moreover, when researchers looked to the landscape itself, they found a gaping absence. Despite extensive field investigations, no glacial erratics—random rocks carried by ancient glaciers—have been found anywhere on Salisbury Plain, including within four kilometers of the monument where all known bluestones lie. There are no surface glacial deposits, no clues embedded in river gravels, no ghostly fingerprints of ice.

If glaciers had delivered even one boulder to the site, we would expect more erratics scattered across the Plain. Their complete absence is deafening.

But what researchers did find were angular fragments near the monument with edge damage consistent with shaping—deliberate chiseling by human hands, not the chaotic abrasion of glacial drag.

Stone 32d and the Shape of Memory

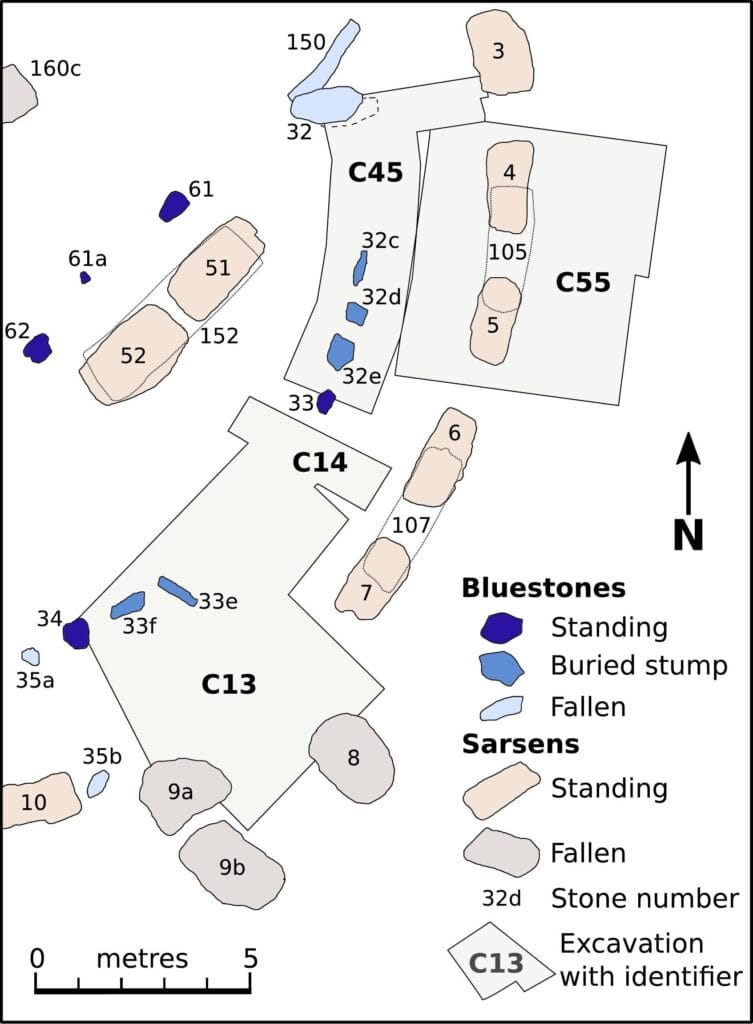

Perhaps most intriguing of all was the morphological evidence. The Newall boulder, with its pointed, bullet-like profile, mirrored the shape of certain rhyolite pillars still in situ at Craig Rhos-y-Felin. It also matched the size and form of a buried monolith at Stonehenge—Stone 32d, a known fragment of a rhyolite pillar. The similarity wasn’t coincidental. It was a smoking gun. The Newall boulder likely broke off from a larger monolith during its shaping, movement, or erection—collateral history, forgotten until now.

In essence, the stone’s shape, texture, and chemistry all told the same story: it was never left by ice. It was placed by people.

The Builders in the Fog of Time

So who were these people who carried stones across hundreds of kilometers, across river valleys, woodlands, and hills, in a time without wheels or beasts of burden?

They remain unnamed, their stories swallowed by centuries, but their actions endure in stone. The transport of the bluestones—of which the Newall boulder is now undeniably one—required not just brute strength, but organization, vision, and reverence. These were not just builders. They were believers. Each stone was more than material; it was meaning. It connected landscape, ancestry, and cosmology in a monument that still captivates our collective imagination.

The discrediting of the glacial hypothesis isn’t just an academic correction. It’s a restoration of human agency to one of the greatest feats in prehistory. The people who built Stonehenge were not passive recipients of natural forces. They were active architects of a sacred world.

Stonehenge, Reimagined

This revelation about the Newall boulder doesn’t simply solve a debate. It reshapes our understanding of Stonehenge itself. Every bluestone on the Plain—buried, broken, or standing—is now more convincingly tied to Neolithic transportation. The idea of purposeful, long-distance megalith movement becomes not speculative but probable. It elevates the monument from a marvel of engineering to a map of cultural connection between far-flung regions of Britain.

Craig Rhos-y-Felin was not a random quarry. It was a destination—a spiritual source, perhaps a homeland of the stones themselves. To bring a piece of it to Salisbury Plain was to carry part of a world’s identity across time and space.

The Newall boulder, unassuming and almost forgotten, becomes a messenger from that age. In its silence, it speaks of travel, of toil, and of the hands that held it.

Conclusion: When Stone Speaks, Listen

The Newall boulder has returned to the stage of history with something profound to say. Not in words, but in the evidence etched into its very being. Aberystwyth University’s meticulous study has not just identified a rock. It has illuminated a story—one in which humans, not glaciers, shaped the legacy of Stonehenge.

In a time when climate and technology drive the future, this look into our past reminds us that human will and wonder have always carved the path forward. Stonehenge is not just a monument of mystery. It is a monument of memory. And sometimes, all it takes to unlock its secrets is the quiet testimony of a single stone fragment, waiting for someone to ask the right question.

Reference: Richard E. Bevins et al, The enigmatic ‘Newall boulder’ excavated at Stonehenge in 1924: New data and correcting the record, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105303