In the golden dawn light sweeping across Kenya’s Amboseli ecosystem, the calls of baboons echo through the acacia trees. Amid the chatter and rustling leaves, an unexpected truth has emerged—a truth about fathers, daughters, and the secret threads that connect survival to affection.

New research from the University of Notre Dame has revealed that baboon fathers, long thought to be fleeting figures in the lives of their offspring, may be quietly shaping the destinies of their daughters in profound ways. In a study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, scientists have discovered that female baboons who grow up with attentive fathers live, on average, two to four years longer than those who lose their fathers early or never forge close bonds with them.

It’s a finding that not only shifts our understanding of baboon social life but also stirs deeper questions about the evolutionary origins of fatherhood—including our own.

The Hidden Side of Baboon Fatherhood

In the wild tapestry of mammal life, paternal care is rare. Among primates and other mammals, mothers are often the sole architects of survival, nursing, grooming, and defending their young. Fathers, when present at all, are often assumed to be mere passersby in the narrative of their children’s lives.

But in the case of baboons, the story is richer and more nuanced.

“Male baboons tend to reach their peak reproductive success when they’re young adults,” said Elizabeth Archie, professor of biological sciences at Notre Dame and corresponding author of the study. “But once they’ve had a few kids and their condition declines, they sort of slide into ‘dad mode.’”

In this so-called “dad mode,” aging male baboons stop roaming in search of new mates and instead remain closer to the social groups where their offspring live. What might look like a slowing down is, in fact, a pivot toward a different kind of investment—the emotional and social nurturing of their young.

Decades of Secrets in the Amboseli Sun

The story of these baboon fathers was uncovered through decades of meticulous observation by the Amboseli Baboon Research Project, one of the longest-running primate studies in the world. Established in 1971, the project has chronicled births, deaths, alliances, and conflicts across generations of baboons beneath the shifting skies of East Africa.

Archie and her colleagues analyzed the lives of 216 female baboons, tracing the footprints of father-daughter relationships from infancy into adulthood. About one-third of these daughters shared their early years with fathers who stayed in the group for at least three years. For the others, fathers either dispersed to new groups or died during the daughters’ first three years of life—a harsh reality in the unpredictable wild.

The scientists looked for clues in grooming behavior, a cornerstone of baboon social life. Grooming, Archie explained, is more than hygiene—it’s the baboon equivalent of “sitting down, having a cup of coffee and a good chat.” It creates bonds, signals trust, and offers a buffer against the stresses of group living.

A Father’s Presence Echoes in Years Gained

The researchers discovered a striking pattern. Daughters who maintained strong bonds with their fathers—either through frequent grooming or simply living together—enjoyed dramatically longer lives than those who grew up without a father’s presence.

“Early life adversity has a powerful effect on lifespan,” Archie said. “So this study suggests that having a dad allows females that have experienced other forms of adversity to recover some of those costs.”

The difference was not trivial. Two to four years of additional life is significant in baboon terms, where the average female lifespan hovers around 18 years. Those extra years could mean more opportunities to bear offspring, build alliances, and leave a legacy.

The Subtle Power of Social Networks

Why do fathers make such a difference?

The study suggests that fathers may act as social bridges. Male baboons are often prominent figures in their groups—respected, watched, and approached by others. For a young female baboon, being near her father could open doors to a richer, safer social life.

“Males seem to sort of expand a child’s social network,” Archie said. “Lots of baboons are coming up and interacting with the male. So an infant who’s hanging out near a male has more diverse social interactions than if they’re only hanging out with mom.”

Moreover, fathers can intervene during conflicts, shielding daughters—and even mothers—from aggression by other group members. They can serve as both bodyguards and social allies, reducing the physical and psychological stress that so often cuts lives short in the animal kingdom.

Interestingly, strong bonds with other adult males outside the father-daughter relationship didn’t offer the same survival advantage. It seems there’s something uniquely powerful about paternal ties.

Rewriting the Narrative of Mammalian Fatherhood

These revelations ripple far beyond the savannas of Kenya. They challenge the long-held notion that mammal fathers are mostly absent players in their offspring’s survival stories.

“In a lot of mammals, dads have a reputation of not contributing very much to offering care,” Archie said. “But we now know that even these seemingly minor contributions that males are making still have really important consequences, at least in baboons.”

Could the seeds of human fatherhood lie hidden in these baboon bonds?

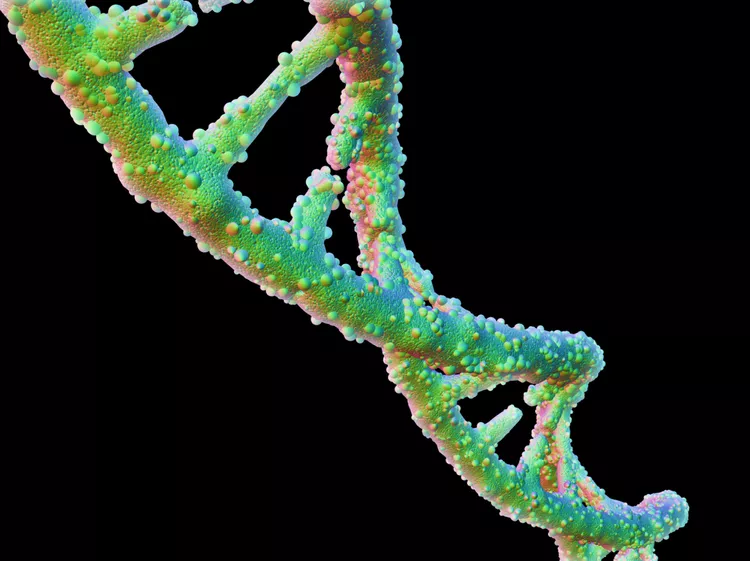

Humans, like baboons, evolved in complex social environments where alliances, protection, and emotional support shape survival. Understanding how fatherhood functions in our primate cousins could illuminate the evolutionary roots of human paternal care, suggesting that the impulse to nurture, protect, and bond might run deeper in the primate family tree than we ever imagined.

A Story Still Unfolding Under African Skies

The Amboseli Baboon Research Project continues, its researchers rising each day with the sun, scanning the landscape for the familiar faces of baboon families. Each day brings new dramas—births, friendships, rivalries, and subtle gestures of care that may hold secrets about our own species.

As baboon fathers linger in the shade, grooming their daughters and watching over their small worlds, they remind us that the threads of love and survival are often intertwined in ways we are only beginning to understand.

In the rustling grasses and warm breezes of Amboseli, science has found another piece of the puzzle of life—a quiet truth whispered between a father and his daughter beneath the African sky.

Reference: David J. Jansen et al, Early-life paternal relationships predict adult female survival in wild baboons, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.0194