Bats are not often thought of as prey — especially not for animals as unremarkable and familiar as brown rats. Yet new footage from northern Germany has captured a startling scene: rats hunting bats with speed, precision, and persistence. In the quiet darkness of bat hibernation sites, infrared and thermal cameras recorded a predator–prey interaction never before documented in urban Europe. What looked like a curiosity at first glance may, according to researchers, represent a serious long-term threat to local bat populations.

A First Look at an Unexpected Urban Predator

Scientists monitoring bat colonies between 2020 and 2024 set up continuous surveillance at two large hibernation sites, located in Segeberg and Lüneburg-Kalkberg. Thousands of bats gather at these locations each winter, crowding together in sheltered spaces that should provide safety — but instead created an opportunity for an opportunistic hunter.

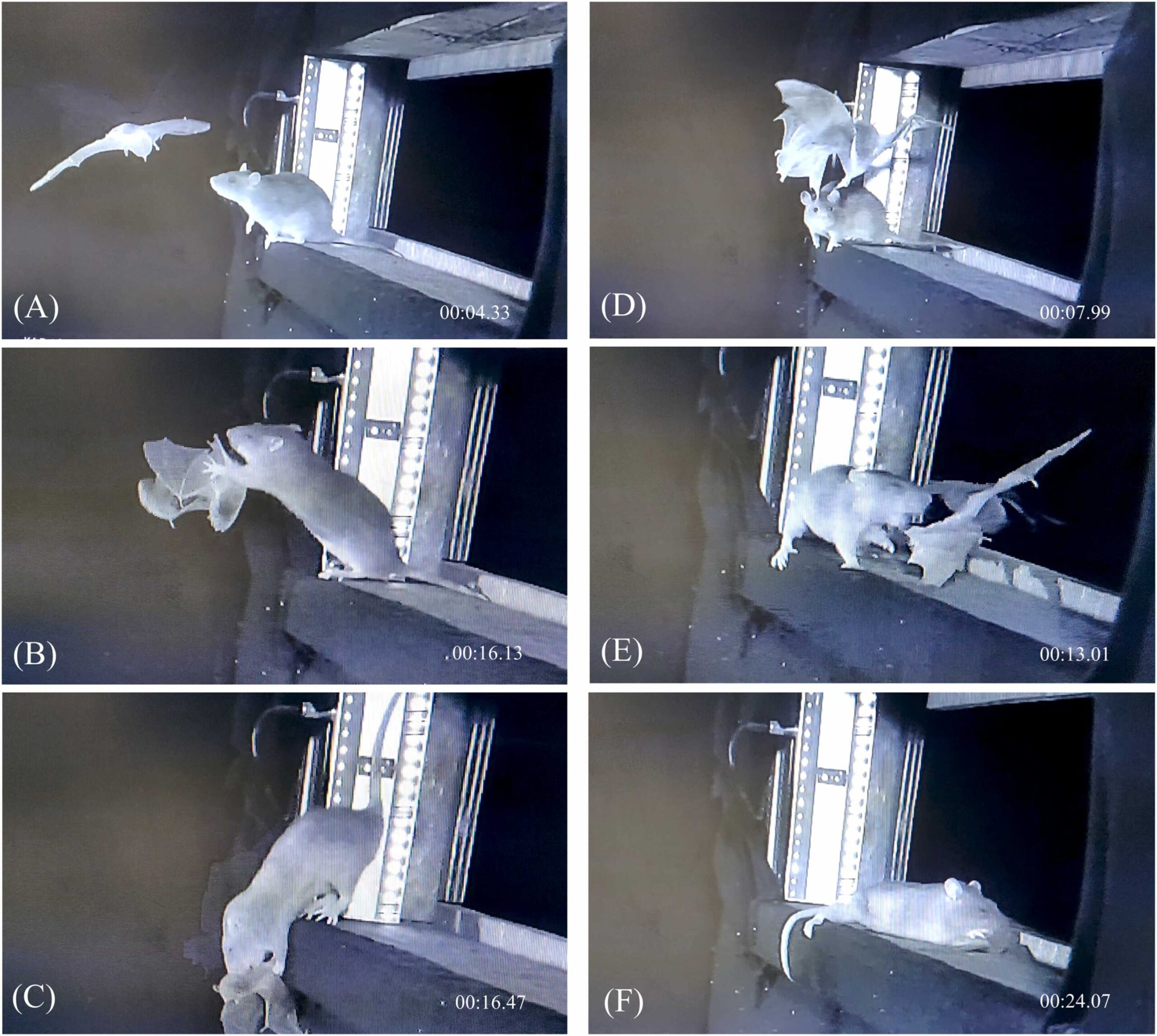

The footage showed two strategies. Some rats balanced upright, using their tails as stabilizers as they grabbed bats mid-air like tiny ambush predators. Others waited until bats were crawling or grounded, then attacked them at close range. At the Segeberg site alone, the cameras confirmed 13 kills within just five weeks — and researchers later uncovered a hidden cache of 52 bat carcasses attributed to rat predation. Similar remains were discovered at Lüneburg-Kalkberg, indicating this was not a one-off behavior but an organized feeding strategy.

Why a Small Number of Kills Can Cause Big Damage

The raw number of kills might seem modest — dozens, not thousands. But the study shows that even a small rat colony could wipe out as much as 7% of Segeberg’s 30,000-bat population in just one winter. This is not just loss of life; it’s loss at a biologically critical moment. Bats in hibernation or swarming are slow, energy-depleted, and unable to flee. Their populations are already slow to recover from disturbance because bats reproduce very slowly — usually one pup per year. A repeated seasonal loss of 7% could drive a stable population into long-term decline.

City Basements Acting Like Islands

In ecological history, invasive rodents have devastated native species on islands by exploiting wildlife forced into dense, vulnerable clusters. The new research suggests that urban environments can mimic this island effect. Underground chambers, basements, tunnels, and other man-made cavities concentrate bats into confined zones, handing rats a dense, predictable food supply. City rats are not just scavengers in trash cans — in these environments they can behave like apex predators.

As the authors note, this finding forces cities to be considered not just as disrupted habitats but as ecological engines that can create extinction-like pressures without anyone noticing.

Why Bat Protection Matters Beyond Wildlife Conservation

The urgency goes far beyond sympathy for bats as a species. Bats are unsung pillars of ecological stability. They devour insects that damage crops and spread disease, reducing the need for chemical pesticides. Some species pollinate plants and disperse seeds that forests depend on. When bat populations collapse, insects surge, agricultural costs rise, and disease risks climb.

This makes bat conservation a public health issue, not only a biodiversity one. Rats heavy with pathogens feeding in the same places where thousands of bats gather could also increase the risk of disease transmission at a human–animal interface. For this reason the researchers emphasize rodent control at key bat sites as part of a “One Health” framework — a strategy that treats environmental health, wildlife health, and human health as inseparable.

A Warning From the Walls

The discovery does not mean rats are suddenly “new predators.” It means that urban design, human neglect, and biological opportunity have quietly created conditions in which an ordinary rodent can gain an extraordinary advantage. Bat populations already stressed by habitat loss, climate shifts, and disease now face a new threat emerging not from wilderness but from beneath the cities they share with us.

The cameras did more than record a rare behavior. They revealed that without intervention, the places humans build for themselves can become traps for the animals we depend on. Whether cities continue to be silent battlefield zones or become protected coexistence zones depends on whether these findings translate into action — sealing access points, managing rodents at hibernation sites, and treating bat conservation not as an optional nicety but as a public good.

What looked like a small dark corner of a German cave has illuminated something much larger: a reminder that when we change environments, we also change who hunts — and who survives.

More information: Florian Gloza-Rausch et al, Active predation by brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) on bats at urban mass hibernacula in Northern Germany: Conservation and one health implications, Global Ecology and Conservation (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03894