Every morning, millions of people wake with a strange feeling: something vivid, emotional, and meaningful just slipped away. A face dissolves, a place fades, a story collapses into fragments. You know you were dreaming, sometimes intensely, sometimes beautifully or terrifyingly, yet within minutes it is gone. This daily disappearance is so common that we accept it as normal, but it hides one of the most fascinating mysteries of the human brain. Why do dreams vanish so easily? Why can something that felt so real, so alive, evaporate almost instantly after waking?

Dream amnesia is not a failure of the mind. It is a feature of how the brain works, shaped by evolution, chemistry, and the delicate balance between consciousness and memory. To understand why we forget our dreams, we must explore how memories form, how sleep alters the brain’s internal environment, and why dreaming exists at all. The answer lies not in a single cause, but in a convergence of neurobiology, emotion, and the architecture of sleep itself.

Dreams as a Unique State of Consciousness

Dreaming is not simply imagination running freely. It is a distinct state of consciousness, fundamentally different from waking thought. During dreams, especially those that occur in rapid eye movement sleep, the brain is highly active, yet awareness of the external world is almost completely shut down. Sensory input is muted, muscles are paralyzed, and the mind turns inward.

In this state, the brain generates experiences that feel immersive and emotionally charged. We see, hear, move, fear, love, and suffer, all without any external stimulus. Yet the rules governing this inner world are different. Logic bends, time distorts, and identities shift. The dreaming brain is creative, associative, and emotional, but it is also biologically constrained in ways that make memory fragile.

Dreams feel real in the moment, but their reality exists within a neural context that is hostile to long-term memory formation. Understanding why requires a closer look at how memory works when we are awake.

How Memory Is Normally Formed

Memory is not a single process. It is a complex choreography involving multiple brain systems working together. When you experience something while awake, sensory information flows into the brain, where it is processed, interpreted, and, if deemed important, encoded into memory.

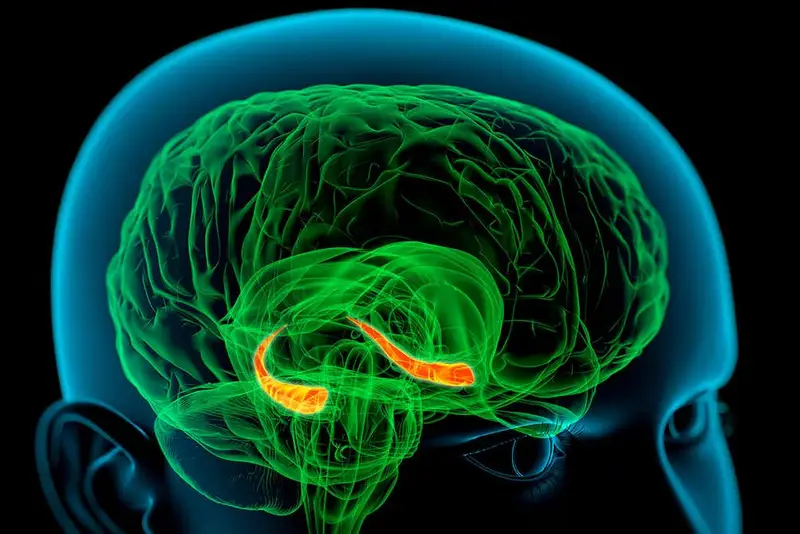

A key player in this process is the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure buried deep in the temporal lobe. The hippocampus acts as a temporary storage and indexing system, binding together different aspects of an experience into a coherent memory. Over time, through repetition and consolidation, these memories are integrated into long-term storage across the cortex.

This process depends heavily on attention, awareness, and neurochemical signals. Certain neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, help mark experiences as significant. They signal the brain to remember, to store, to reinforce neural connections. Without these signals, experiences tend to fade.

Dreaming occurs in a neurochemical environment where many of these memory-supporting signals are altered or suppressed.

The Neurochemical Landscape of Dreaming

During dreaming, especially in rapid eye movement sleep, the brain’s chemistry shifts dramatically. Some neurotransmitters surge, while others drop to unusually low levels. These changes shape the dream experience, but they also undermine the brain’s ability to form lasting memories.

One of the most important changes involves norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter associated with alertness, attention, and memory encoding. In waking life, norepinephrine helps the brain tag experiences as important and worthy of storage. During rapid eye movement sleep, norepinephrine activity drops to near zero. This absence creates a mental world that is emotionally vivid but poorly anchored in memory.

Serotonin and histamine, which also support stable cognition and memory, are similarly reduced. Meanwhile, acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter involved in activation and imagery, is high. This imbalance creates a brain that is active and creative but not well-equipped to store what it experiences.

In essence, the dreaming brain is designed to experience, not to remember.

The Hippocampus Goes Offline

The hippocampus plays a crucial role in transforming experiences into memories, but during dreaming, its function is altered. Research suggests that hippocampal activity during rapid eye movement sleep is reduced or functionally disconnected from cortical regions involved in conscious recall.

This does not mean the hippocampus is inactive. In fact, it plays a role in memory consolidation during sleep, but this is a different function. Rather than encoding new experiences, the hippocampus replays and reorganizes existing memories, strengthening connections and integrating information.

Dreams may emerge as a byproduct of this internal processing. The brain is sorting, associating, and reactivating memories, and the subjective experience of this activity is the dream. However, because the hippocampus is focused on reprocessing old information rather than encoding new narratives, the dream itself is not treated as something to be remembered.

The dream is like a stage play performed during a rehearsal, meaningful to the actors but never intended for an audience.

Emotional Intensity Without Memory Stability

One of the most confusing aspects of dream amnesia is the emotional power of dreams. How can something so emotionally intense be so easily forgotten? Emotion, after all, is usually a powerful enhancer of memory.

The answer lies in the type of emotion and how it is processed during sleep. The amygdala, a brain region involved in emotion and threat detection, is highly active during dreaming. This contributes to the strong feelings of fear, joy, sadness, or desire that dreams often evoke.

However, emotional activation alone is not enough to create lasting memories. Emotional experiences need to be integrated with contextual and narrative frameworks, processes that rely on stable hippocampal and prefrontal cortex activity. During dreaming, the prefrontal cortex, which supports logic, self-awareness, and narrative coherence, is relatively inactive.

As a result, dream emotions are intense but poorly structured. They surge and dissipate without being anchored to a clear sense of self, time, or place. Without this structure, memories cannot easily consolidate.

The emotion burns brightly, but there is nothing solid for it to attach to.

The Role of the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is essential for reflective awareness, decision-making, and memory organization. It helps you understand that you are you, that events follow a sequence, and that experiences can be evaluated and recalled later.

During most dreams, the prefrontal cortex is significantly less active. This explains why dreams often lack logic, why we accept bizarre situations without question, and why we rarely reflect on the dream while it is happening.

This reduced prefrontal activity also means that the brain does not engage in metacognition, the awareness of one’s own mental processes. Without metacognition, experiences are not tagged as events to be remembered. They are simply lived.

Lucid dreaming, where the dreamer becomes aware they are dreaming, offers a powerful clue. In lucid dreams, prefrontal activity increases, and dream recall is often better. This suggests that awareness and reflective processing play a key role in whether dreams are remembered.

Sleep Stages and Memory Fragility

Not all dreams are equally forgettable. Dreams can occur in different stages of sleep, and recall varies accordingly. Rapid eye movement sleep is most strongly associated with vivid, narrative dreams, but it is also the stage most associated with dream amnesia.

Non-rapid eye movement sleep can also produce dreams, often more thought-like and less emotionally intense. These dreams sometimes resemble waking concerns and may be easier to remember, especially if they occur closer to waking.

Timing matters. Dreams that occur just before awakening are more likely to be recalled because the brain transitions more smoothly into a waking neurochemical state. When awakening is abrupt, or when there is a delay between the dream and conscious awareness, the fragile memory trace often dissolves.

Dream memory exists in a narrow window. Miss that window, and the dream disappears.

Evolutionary Perspectives on Dream Forgetting

From an evolutionary standpoint, forgetting dreams may not be a flaw but an advantage. Dreams often involve simulated scenarios, emotional rehearsals, and memory recombination. Their purpose may be to process information, not to produce experiences that need to be remembered.

If every dream were stored as a memory, the mind might struggle to distinguish between real and simulated experiences. This could blur reality, impair decision-making, and create confusion. Dream amnesia may serve as a protective filter, preserving the integrity of waking memory.

In this view, dreams are like internal training simulations. They are useful while they happen, shaping emotional responses and reinforcing learning, but they do not need to be remembered consciously to fulfill their function.

Dreams as Memory Processing, Not Memory Products

One of the most compelling scientific views of dreaming is that dreams reflect memory processing rather than memory creation. During sleep, the brain reactivates fragments of past experiences, emotions, and knowledge, reorganizing them into new associations.

This process helps consolidate learning, extract patterns, and regulate emotional responses. Dreams may be the subjective experience of this internal work. They borrow elements from memory, but they are not meant to become memories themselves.

This explains why dreams often feel familiar yet strange, why they mix people and places from different times, and why they rarely form coherent narratives. The brain is not telling a story for recall; it is rearranging its internal library.

Forgetting the dream does not mean the process failed. It may mean it succeeded.

The Fragility of State-Dependent Memory

Memory retrieval depends on context. What you remember is strongly influenced by your mental and physiological state. Dreams occur in a brain state radically different from waking consciousness.

When you wake up, the brain’s chemistry shifts rapidly. Neurotransmitters return, sensory input floods in, and attention turns outward. This abrupt change makes it difficult to access memories formed in the dreaming state.

Dream memories are state-dependent. They are easiest to recall when the brain remains close to the dream state, such as during brief awakenings or quiet reflection. Once fully awake, the bridge to the dream state collapses.

This is why dreams often feel just out of reach, like words on the tip of the tongue. The memory exists, but the state needed to retrieve it is gone.

Individual Differences in Dream Recall

Some people remember dreams frequently, while others almost never do. This variation reflects differences in brain activity, sleep patterns, personality traits, and attention to dreams.

Research suggests that people who recall dreams often have greater connectivity between memory-related brain regions and areas involved in self-reflection. They may also wake up more frequently during the night, increasing opportunities for recall.

Interest matters too. Paying attention to dreams, reflecting on them upon waking, and rehearsing them mentally can strengthen fragile memory traces. This does not change the nature of dream amnesia, but it can work within its constraints.

The brain remembers what it is encouraged to remember.

Stress, Sleep Quality, and Dream Forgetting

Stress and poor sleep can influence both dreaming and recall. High stress levels alter sleep architecture, reducing rapid eye movement sleep or fragmenting it. This can lead to fewer vivid dreams or dreams that are harder to remember.

At the same time, stress hormones can interfere with memory processes. A stressed brain may prioritize survival-related functions over reflection and recall. Even if dreams occur, their memory traces may be weaker.

Paradoxically, intense emotional stress can sometimes increase dream vividness while still impairing recall. The dreams feel powerful but vanish quickly, leaving behind only a lingering mood.

The Myth of the Forgotten Dream Meaning Nothing

It is tempting to assume that forgotten dreams are meaningless. If they mattered, surely we would remember them. Neuroscience suggests otherwise.

Much of the brain’s most important work happens without conscious awareness. Memory consolidation, emotional regulation, and learning often occur silently. Dreams may influence mood, creativity, and problem-solving even when their content is forgotten.

Many people experience insights, emotional shifts, or creative ideas upon waking without remembering the dream that shaped them. The effect remains even when the story is gone.

Forgetting a dream does not erase its impact.

Dreams, Identity, and the Sense of Self

Dream amnesia also reflects how the sense of self changes during sleep. In dreams, the self is fluid. You may act without intention, shift identities, or observe yourself from outside. This unstable sense of self makes it harder to encode experiences as belonging to a continuous personal narrative.

Waking memory relies on a stable identity. You remember events because they happened to you, in a timeline that makes sense. Dreaming disrupts this structure. The self becomes a character rather than an author.

Without a stable narrator, memories lack an anchor.

The Transition from Dream to Wakefulness

The moment of waking is critical. If the transition is gentle, dream recall is more likely. If it is abrupt, the dream often vanishes instantly.

External stimuli, alarms, sudden movements, and immediate engagement with the day can overwrite dream memory traces. The brain prioritizes the present moment, suppressing fragile internal experiences.

This is why lying still, eyes closed, and reflecting upon waking can help recall. It keeps the brain close to the dream state long enough for memory consolidation to occur.

Even then, recall is often partial. Fragments emerge, but the whole rarely survives.

Why the Brain Chooses Forgetting

Ultimately, dream amnesia reflects a trade-off. The brain balances the need to process information with the need to maintain a coherent, functional waking life.

Remembering everything is not always beneficial. Selective forgetting allows the brain to focus on what matters for survival, learning, and identity. Dreams serve internal functions that do not require conscious recall.

Forgetting dreams may be the price we pay for a mind that can distinguish imagination from reality, simulation from experience, night from day.

The Mystery That Remains

Despite advances in neuroscience, dreaming remains one of the most mysterious aspects of the human mind. We understand many mechanisms, but the full purpose of dreams is still debated.

Dream amnesia is part of this mystery. It reminds us that consciousness is layered, that not all experiences are meant to be carried forward, and that the mind operates on multiple levels at once.

Every forgotten dream is a reminder that the brain is not just a recorder of experience, but an active, selective, and creative system.

Living With the Forgotten Night

Each night, the mind journeys through landscapes we may never consciously know. It processes fears, hopes, memories, and possibilities, weaving them into ephemeral stories that dissolve with the morning light.

We wake with empty hands, yet something has changed. A feeling lingers. A thought emerges. A problem feels lighter. The dream is gone, but its work remains.

Dream amnesia is not a loss. It is a quiet exchange. We give up the memory of the dream, and in return, the brain gives us a mind better prepared for waking life.

In forgetting our dreams, we are not failing to remember. We are participating in one of the most subtle and profound functions of the human brain, a nightly act of transformation that happens beyond awareness, shaping who we are while we sleep.