Sadness is a universal human emotion, as ancient as love and as familiar as hunger. It arrives quietly sometimes, as a passing shadow, and other times it settles deeply, changing how the world feels, how time moves, how the self is perceived. When sadness becomes persistent, heavy, and life-altering, it may grow into depression. Depression is not merely a state of mind or a failure of will. It is a biological, psychological, and social condition rooted deeply in the brain and body. To understand depression at its most intimate level is to look inward, beyond feelings and behaviors, into molecules, cells, circuits, and genes. Inside the depressed brain, chemistry shifts, communication falters, and systems meant to protect and motivate instead contribute to suffering.

This is the molecular story of sadness, a story written in neurotransmitters and hormones, in receptors and synapses, in inflammation and altered energy flow. It is also a deeply human story, because every molecular change echoes outward into thought, memory, motivation, and hope.

Sadness and Depression: From Experience to Biology

Sadness, in its ordinary form, is a healthy emotional response. It signals loss, disappointment, or unmet needs. In the brain, transient sadness corresponds to temporary changes in neural activity and chemistry. These changes are adaptive, allowing reflection, withdrawal, and emotional processing. Depression, however, represents a breakdown of this adaptive system. Instead of resolving, sadness becomes chronic, often accompanied by emotional numbness, hopelessness, fatigue, and cognitive distortion.

From a biological perspective, depression is not caused by a single defect. It is a network-level disorder involving multiple molecular pathways that interact over time. These pathways include neurotransmitter systems, stress hormones, immune signaling, neuroplasticity mechanisms, and gene regulation. Depression emerges when these systems fall out of balance and remain dysregulated.

Understanding this complexity is crucial, because it explains why depression feels all-encompassing and why simple explanations fail to capture its reality.

Neurotransmitters: The Chemical Messengers of Mood

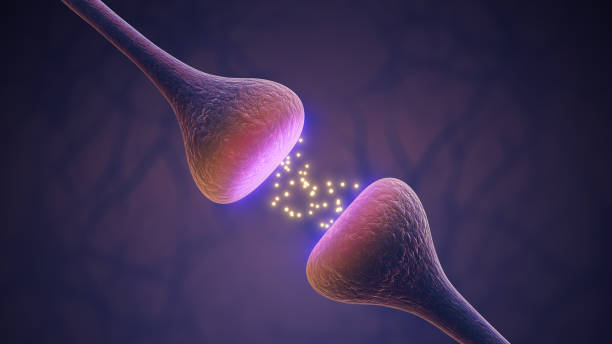

At the core of brain communication are neurotransmitters, chemical messengers that allow neurons to signal one another across synapses. For decades, depression has been associated with disruptions in neurotransmitter systems, particularly serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. While no longer considered the sole cause of depression, these molecules remain central to its biology.

Serotonin is often described as a mood stabilizer, but its role is far richer. It influences emotional regulation, impulse control, sleep, appetite, and social behavior. In a depressed brain, serotonin signaling is often altered, not necessarily because serotonin is absent, but because receptors, transporters, and downstream signaling pathways are changed. The same amount of serotonin may produce a weaker or distorted effect.

Dopamine is deeply tied to motivation, reward, and pleasure. When dopamine signaling is disrupted, the world loses its color. Activities that once brought joy feel empty. This anhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure, is one of the most painful aspects of depression. At the molecular level, dopamine neurons may fire less frequently, release less neurotransmitter, or respond differently to rewards.

Norepinephrine helps regulate alertness, energy, and the stress response. In depression, norepinephrine systems may become blunted or dysregulated, contributing to fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and a sense of being overwhelmed by even small tasks.

These neurotransmitter systems do not operate in isolation. They form interconnected networks, influencing one another and shaping large-scale brain activity patterns. Depression reflects not a single chemical deficiency but a reorganization of chemical communication.

Synapses and Receptors: When Communication Weakens

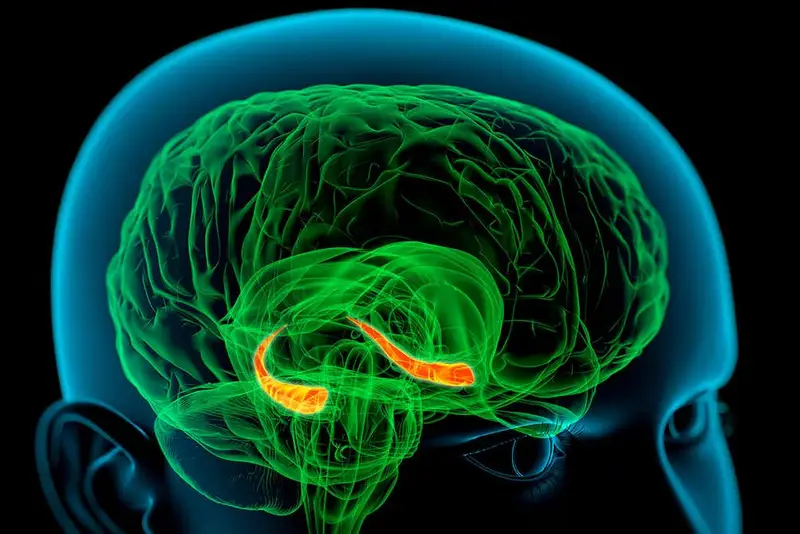

Neurotransmitters exert their effects by binding to receptors on neurons. These receptors are proteins embedded in cell membranes, finely tuned to respond to specific signals. In depression, receptor function often changes. Some receptors become less sensitive, others more active, altering how neurons respond to incoming messages.

At the synaptic level, depression is associated with reduced synaptic density in certain brain regions, particularly the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. These areas are crucial for decision-making, emotional regulation, and memory. Fewer synapses mean reduced communication capacity, as if the brain’s internal conversation has grown quieter and less flexible.

This synaptic loss is not merely structural; it is molecular. Proteins that support synapse formation and maintenance, such as those involved in cytoskeletal stability and signal transduction, are often downregulated in depression. The brain becomes less able to adapt, learn, and recover from stress.

Neuroplasticity: The Brain’s Capacity to Change

One of the most important molecular concepts in modern depression research is neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to change its structure and function in response to experience. Healthy plasticity allows learning, memory, and emotional resilience. Depression is increasingly understood as a disorder of impaired plasticity.

A key molecule in this process is brain-derived neurotrophic factor, often described as a fertilizer for neurons. It supports neuron survival, growth, and synaptic strength. In many people with depression, levels of this molecule are reduced in critical brain regions. Lower levels mean neurons are more vulnerable to stress and less capable of forming new connections.

This reduction in plasticity helps explain why depressed thinking feels rigid and repetitive. Negative thoughts loop endlessly. Alternative perspectives feel inaccessible. At the molecular level, the brain is less able to rewire itself in response to positive experiences.

Stress Hormones and the Burden of Cortisol

Stress is not inherently harmful. Acute stress can sharpen focus and mobilize energy. The problem arises when stress becomes chronic. The body’s primary stress system, known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, plays a central role in depression.

When stress is perceived, this system releases cortisol, a hormone that prepares the body for action. In a healthy system, cortisol levels rise and fall in a controlled rhythm. In many depressed individuals, this rhythm is disrupted. Cortisol may remain elevated or fluctuate abnormally.

At the molecular level, excess cortisol affects neurons directly. It can reduce neuroplasticity, suppress the formation of new neurons in the hippocampus, and alter gene expression. Cortisol also interacts with neurotransmitter systems, further disrupting mood regulation.

Over time, the brain’s stress response becomes hypersensitive, reacting strongly even to minor challenges. This creates a feedback loop in which stress worsens depression, and depression amplifies the perception of stress.

Inflammation: The Immune System Enters the Brain

One of the most striking discoveries in recent years is the role of inflammation in depression. Traditionally, the brain was considered separate from the immune system. This view has changed dramatically. The immune system communicates with the brain through signaling molecules called cytokines.

In many people with depression, levels of inflammatory cytokines are elevated. These molecules can cross into the brain or signal through neural pathways, altering neurotransmitter metabolism, reducing plasticity, and increasing sensitivity to stress.

Inflammation can decrease serotonin availability by diverting its precursor molecules into alternative metabolic pathways. It can also impair dopamine signaling, contributing to fatigue and anhedonia. At the cellular level, inflammation affects glial cells, the brain’s support cells, altering how they regulate synapses and neuronal health.

This inflammatory perspective helps explain why depression often accompanies chronic illness, infection, or prolonged stress. It also reinforces the idea that depression is a whole-body condition, not confined to the mind.

Mitochondria and Energy in the Depressed Brain

Every thought, emotion, and action requires energy. That energy is produced by mitochondria, tiny structures within cells that convert nutrients into usable fuel. Emerging research suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction may play a role in depression.

In a depressed brain, energy metabolism may be less efficient. Neurons may struggle to meet the energetic demands of complex signaling and plasticity. This energetic deficit can manifest subjectively as mental exhaustion, slowed thinking, and a sense that even simple tasks require immense effort.

At the molecular level, impaired mitochondrial function increases oxidative stress, damaging cellular components and further disrupting signaling pathways. This creates another layer of vulnerability, linking metabolic health to emotional well-being.

Gene Expression and Epigenetic Change

Genes provide the blueprint for brain function, but they are not static instructions. Their expression changes in response to environment and experience. Depression is associated not only with genetic risk but with changes in how genes are turned on or off.

Stress, trauma, and chronic adversity can leave molecular marks on DNA-associated proteins, a process known as epigenetic modification. These changes alter gene expression without changing the genetic code itself. In the depressed brain, epigenetic modifications can affect genes involved in neurotransmission, plasticity, and stress regulation.

These molecular memories of experience help explain why depression can persist long after the original stressor has passed. They also explain why early-life adversity can increase vulnerability to depression later in life.

Brain Circuits and Emotional Bias

Molecules shape cells, cells shape circuits, and circuits shape experience. In depression, the balance of activity between brain regions is altered. The amygdala, involved in threat detection and emotional intensity, often becomes hyperactive. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for regulation and perspective, may become less active or less effective.

At the molecular level, these circuit changes reflect altered neurotransmitter signaling, receptor sensitivity, and synaptic strength. Negative information is processed more readily, remembered more vividly, and felt more intensely. Positive information struggles to register.

This biased processing is not a choice. It is the product of altered molecular and cellular dynamics that tilt perception toward sadness and hopelessness.

Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Molecular Timekeeping

Sleep disturbance is both a symptom and a contributor to depression. The brain operates on circadian rhythms regulated by molecular clocks within cells. These clocks coordinate hormone release, neurotransmitter activity, and gene expression.

In depression, circadian rhythms often become desynchronized. Sleep may be fragmented, delayed, or excessive. At the molecular level, disruptions in clock gene expression affect serotonin and dopamine systems, stress hormones, and immune signaling.

This disruption creates a vicious cycle. Poor sleep worsens mood and cognitive function, while depression further impairs sleep. Restoring rhythmicity is increasingly recognized as a key component of recovery.

Why Depression Feels So Real and So Physical

People suffering from depression often struggle with the belief that their pain is somehow unreal or illegitimate. The molecular basis of sadness tells a different story. Depression is embodied. It is written into the chemistry of synapses, the firing of neurons, the expression of genes.

The heaviness, the fog, the exhaustion, and the emotional pain are not imagined. They are the subjective experience of real biological changes. Understanding this does not reduce depression to “just chemistry,” but it affirms that suffering has a physical foundation deserving of compassion and care.

Healing and Molecular Change

Although this article focuses on what goes wrong in depression, the same molecular systems also support recovery. Neuroplasticity can be restored. Inflammation can subside. Neurotransmitter signaling can rebalance. Gene expression can shift.

Different forms of treatment, whether psychological, pharmacological, or social, converge on these molecular pathways. They create conditions that allow the brain to rewire, to regain flexibility, and to respond to the world with renewed openness.

Hope, at the molecular level, is not abstract. It is the gradual reactivation of systems that allow connection, meaning, and joy to return.

The Molecular Story as a Human Story

The molecular basis of sadness is not a cold or distant narrative. It is a deeply human one. Every molecule involved in depression is part of a living system shaped by experience, relationships, and environment. Biology does not negate meaning; it carries it.

To understand what happens inside a depressed brain is to recognize the profound complexity of emotion. Sadness is not weakness. Depression is not failure. They are expressions of a brain struggling under altered molecular conditions.

By looking closely at these invisible processes, we do more than advance science. We deepen empathy. We replace judgment with understanding. And we remember that even in the depths of sadness, the brain remains a living, changing organ, capable of healing, connection, and renewal.