Depression often feels like a prison built inside the mind. Thoughts loop endlessly, emotions flatten or ache, and the future seems sealed by an invisible force that says, “This is how it will always be.” For decades, many people believed that this feeling was permanent because the brain itself was fixed—hardwired early in life and largely unchangeable thereafter. If depression took hold, it was assumed to be a lifelong condition to manage, not a state the brain could truly move beyond.

But modern neuroscience has quietly and profoundly changed this story. At the center of that change is a concept called neuroplasticity: the brain’s lifelong ability to change its structure, function, and patterns of activity in response to experience. This discovery has transformed how scientists understand learning, recovery, trauma, and hope. It has also reshaped how we think about depression—not as a static flaw in the brain, but as a dynamic state that can shift over time.

This raises a powerful, emotionally charged question: can you really rewire your brain for joy? The answer is neither a simplistic yes nor a hopeless no. It is more nuanced, more human, and more demanding than popular slogans suggest. Neuroplasticity does not promise instant happiness, but it does offer something far more meaningful: the possibility of change, even after long periods of suffering.

Understanding Depression Beyond Mood

Depression is often misunderstood as sadness, but clinically and biologically it is far more complex. It affects how a person thinks, feels, remembers, sleeps, eats, and perceives the world. It alters motivation, attention, and the sense of meaning itself. For many, depression is not an emotional storm but an emotional absence—a numbness that feels just as unbearable.

From a neurological perspective, depression is associated with changes in brain activity and connectivity. Certain regions involved in emotion regulation, reward processing, memory, and self-referential thinking behave differently during depressive states. Stress hormones may remain elevated, neural circuits may become rigid, and the brain may repeatedly default to negative interpretations of experience.

Importantly, these changes are not signs of a broken brain. They are signs of a brain that has adapted to prolonged stress, loss, trauma, or genetic vulnerability. Depression reflects learned patterns—deeply ingrained, yes, but learned nonetheless. And what is learned can, under the right conditions, be reshaped.

What Neuroplasticity Really Means

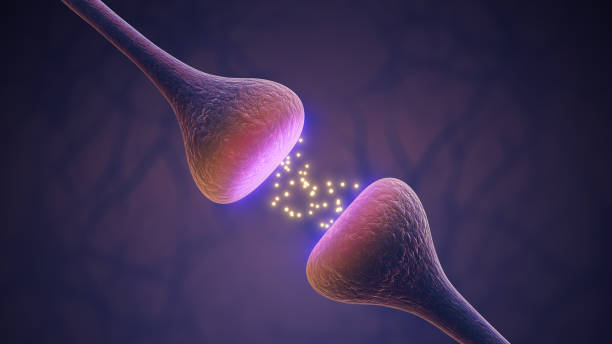

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neurons that fire together tend to wire together, strengthening certain pathways while others weaken through lack of use. This process occurs at multiple levels, from microscopic changes at synapses to large-scale reorganization of entire brain networks.

For much of the twentieth century, scientists believed that the adult brain was essentially fixed. Neurons were thought to die off with age, and recovery from brain injury was assumed to be minimal. This view collapsed when researchers discovered that new neurons can form in certain brain regions and that existing neurons can change their connections dramatically in response to experience.

Neuroplasticity is not inherently positive or negative. The brain adapts to what it repeatedly experiences. Chronic stress can wire the brain toward hypervigilance and fear. Persistent rumination can strengthen circuits that support self-criticism. At the same time, repeated experiences of safety, mastery, and connection can strengthen circuits associated with resilience and emotional balance.

In depression, plasticity has often worked against the individual. But that same capacity can be recruited for healing.

The Depressed Brain as a Plastic Brain

One of the most hopeful insights from neuroscience is that depression itself reflects plasticity. The brain has changed—but not irreversibly. Patterns of thought such as hopelessness, worthlessness, and catastrophizing are not merely “bad habits” in a moral sense; they are reinforced neural pathways that have become efficient through repetition.

Similarly, emotional numbness or constant sadness can emerge when reward-related circuits become less responsive over time. Stress-related changes in brain chemistry and connectivity can make it harder for positive experiences to register fully, creating the painful sense that joy is inaccessible.

Yet the fact that these patterns formed means they were shaped by experience. That implies they can also be reshaped. Neuroplasticity does not erase the past, but it allows the brain to learn new ways of responding to the present.

This reframes recovery from depression not as fixing a defect, but as guiding a learning process—one that involves patience, repetition, and compassion.

Joy as a Neural Process, Not a Personality Trait

Joy is often romanticized as something some people are simply born with and others are denied. Neuroscience tells a different story. Joy, like sadness or fear, is a brain state arising from coordinated activity across multiple neural systems. It involves reward circuits, emotional regulation networks, memory systems, and bodily signals.

In depression, these systems often fall out of balance. The brain becomes more sensitive to negative information and less responsive to positive input. Over time, this bias can make joy feel foreign or even threatening.

Importantly, joy is not the same as constant happiness or excitement. Neurobiologically, joy often appears as moments of engagement, interest, warmth, or meaning. These experiences can be subtle, especially early in recovery. The depressed brain may initially register them faintly, like distant signals breaking through static.

Neuroplasticity suggests that repeatedly noticing and engaging with these signals—however small—can strengthen the neural pathways that support them. Joy is not installed overnight; it is cultivated through repeated experience and attention.

Stress, Trauma, and the Plastic Brain

Many cases of depression are deeply intertwined with stress and trauma. Chronic stress floods the brain with stress hormones that alter neural functioning, especially in regions involved in memory, emotion, and executive control. Over time, the brain adapts by prioritizing threat detection over exploration and connection.

Trauma can intensify this process. When the brain learns that the world is unsafe, it organizes itself accordingly. Depression can emerge as a protective shutdown—a way of conserving energy and minimizing pain when escape or resolution feels impossible.

Neuroplasticity explains both the depth of these wounds and the possibility of healing. Just as repeated danger can wire the brain toward fear and numbness, repeated safety can wire it toward regulation and trust. This does not mean forgetting trauma, but it does mean that the brain can learn new responses alongside old memories.

Healing often requires experiences that contradict the brain’s learned expectations, delivered consistently and gently enough that the nervous system can tolerate them.

Antidepressants and Plasticity

Medications used to treat depression do not simply “add happiness chemicals” to the brain. Their deeper effect appears to involve neuroplasticity. Many antidepressants influence the brain’s ability to form and modify connections, making it more receptive to change.

This is a crucial point. Medication often does not create joy on its own. Instead, it may reduce rigidity, soften emotional extremes, or reopen windows of learning that depression had closed. In this sense, medication can support neuroplasticity by making it easier for new patterns to take hold.

This also explains why medication often works best in combination with psychotherapy or meaningful life changes. The brain becomes more flexible, but it still needs new experiences to learn from. Neuroplasticity is always experience-dependent.

Psychotherapy as Guided Brain Change

Psychotherapy is one of the most direct ways to harness neuroplasticity for recovery from depression. Though it happens through conversation, its effects are biological. Changing patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior alters neural activity and connectivity over time.

Therapeutic approaches help individuals recognize and interrupt maladaptive patterns such as rumination, avoidance, and self-criticism. With repetition, healthier patterns begin to feel more natural, not because of willpower alone, but because the brain has reorganized itself.

Importantly, therapy also provides corrective emotional experiences. Feeling understood, safe, and validated in a therapeutic relationship can directly counter the isolation and self-blame that depression reinforces. These relational experiences are powerful drivers of plastic change, especially in brain systems shaped by early attachment and social learning.

The Role of Attention in Rewiring the Brain

Attention is one of the brain’s most powerful sculptors. What we repeatedly attend to becomes more prominent in neural processing. Depression often narrows attention toward loss, failure, and perceived inadequacy. This narrowing strengthens circuits that support despair.

Training attention differently does not mean denying pain or forcing positivity. Instead, it involves gently broadening awareness to include neutral or positive experiences alongside difficult ones. Over time, this expanded attention can reduce the brain’s automatic bias toward negativity.

Practices that cultivate awareness, such as mindfulness, appear to influence brain regions involved in emotion regulation and self-referential processing. By changing how attention is deployed, these practices can gradually alter the brain’s default patterns.

Movement, Body, and Brain Change

The brain does not exist in isolation from the body. Physical movement sends powerful signals that influence mood, cognition, and neural plasticity. Regular movement has been shown to support the growth of new neural connections and enhance the brain’s capacity for adaptation.

For someone with depression, movement can feel nearly impossible. Energy is low, motivation is blunted, and self-judgment is often harsh. From a neuroplastic perspective, even small amounts of movement can matter. The brain responds not to perfection, but to consistency.

Movement also reconnects individuals with their bodies, countering the dissociation and numbness that often accompany depression. This embodied engagement can support emotional processing and reinforce a sense of agency.

Sleep and the Plastic Brain

Sleep plays a critical role in neuroplasticity. During sleep, the brain consolidates learning, regulates emotional circuits, and clears metabolic byproducts of neural activity. Depression frequently disrupts sleep, creating a vicious cycle that further impairs brain function.

Improving sleep does not merely restore energy; it restores the brain’s ability to change. Even modest improvements in sleep quality can enhance emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility, creating a foundation for further recovery.

Social Connection and Neural Rewiring

Human brains are social brains. Social interaction shapes neural development from infancy onward, and its influence continues throughout life. Depression often drives isolation, which deprives the brain of one of its most important sources of regulation and plastic change.

Positive social experiences activate brain networks involved in reward, safety, and meaning. Feeling seen and valued can counteract the neural patterns of worthlessness that depression reinforces. Over time, repeated social connection can reshape expectations about relationships and self-worth.

This does not mean forcing socialization when it feels overwhelming. Neuroplasticity respects pacing. Even brief, manageable connections can contribute to change when they are consistent and emotionally meaningful.

The Myth of Instant Rewiring

Popular discussions of neuroplasticity sometimes promise rapid transformation: think differently, and your brain will change overnight. This myth can be damaging. When change does not happen quickly, individuals may blame themselves, reinforcing depression.

In reality, neuroplastic change is gradual. The brain has been practicing depressive patterns for months or years. New patterns require repetition, safety, and time. Progress often appears uneven, with setbacks that are part of the learning process rather than signs of failure.

Understanding this can itself be therapeutic. It reframes recovery as a process rather than a test of willpower.

Pain, Acceptance, and Plasticity

An important paradox in depression recovery is that resisting pain too forcefully can reinforce it. Neuroplasticity does not respond well to internal warfare. When individuals learn to acknowledge pain without judgment, they reduce the stress response that keeps depressive circuits activated.

Acceptance does not mean resignation. It means allowing the brain to experience emotion without adding layers of fear or self-criticism. This creates conditions under which new learning can occur.

Can the Brain Truly Learn Joy Again?

The most honest answer is that joy may not return in the same way it once existed. Depression changes people, and recovery does not erase history. But the brain can learn new forms of joy—often quieter, deeper, and more grounded than before.

Neuroplasticity supports the capacity for meaning, connection, and engagement even after profound suffering. Many individuals report that recovery involves not becoming who they were before depression, but becoming someone new—more aware, more compassionate, more attuned to life’s subtleties.

Hope Without Pressure

Perhaps the most important gift of neuroplasticity is hope without guarantee. It says change is possible, not inevitable. It honors effort without demanding perfection. It invites curiosity rather than self-blame.

For someone living with depression, this kind of hope can be life-sustaining. It shifts the question from “What is wrong with me?” to “What is my brain trying to learn, and how can I help it learn something kinder?”

A Living, Learning Brain

The human brain is not a static object but a living process. Depression is not a final verdict written into neural tissue. It is a state shaped by experience, biology, and context—and therefore open to transformation.

Rewiring the brain for joy is not about chasing constant happiness. It is about gradually expanding the brain’s capacity to feel, to connect, and to find meaning again. Neuroplasticity does not promise an easy path, but it offers something more enduring: the knowledge that even in darkness, the brain remains capable of change.

In that knowledge lies a quiet, powerful form of joy—the joy of possibility, the joy of becoming, and the joy of knowing that the story is not finished yet.