The phrase “gut feeling” sounds poetic, almost mystical, as if emotion rises from instinct rather than biology. Yet beneath the poetry lies a startling scientific truth: your gut is not just a digestive tube, and your emotions are not confined to your brain. The human body is threaded together by conversations—chemical, electrical, microbial—and one of the most influential conversations shaping your mood unfolds deep within your intestines. There, trillions of microorganisms form a living ecosystem known as the gut microbiome, and their influence reaches far beyond digestion. They whisper to your nervous system, shape your immune responses, alter your hormones, and quietly help decide whether you feel calm or anxious, hopeful or low.

To understand gut feelings is to understand that mood is not born in isolation. It is co-created by the brain, the body, and the microscopic life that calls us home.

The Gut as a Living Ecosystem

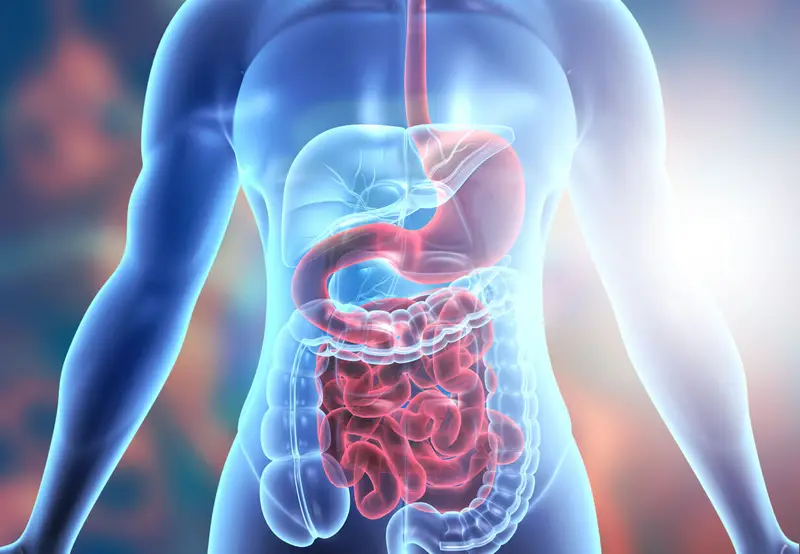

Inside the human gut lives a community so vast it rivals entire forests in complexity. Bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes inhabit the digestive tract from mouth to colon, with the densest populations residing in the large intestine. This ecosystem begins forming at birth and evolves throughout life, shaped by diet, environment, stress, illness, medication, and age.

These microbes are not passive passengers. They eat what we eat, break down compounds we cannot digest on our own, and produce a wide array of biologically active molecules. Some of these molecules nourish the cells lining the gut, others enter the bloodstream, and some interact directly with the nervous system. In return, the body provides warmth, nutrients, and a stable habitat. This relationship is not merely coexistence; it is symbiosis.

From the earliest days of life, this microbial ecosystem helps train the immune system, influences metabolism, and shapes the development of neural pathways. The gut microbiome becomes, in effect, an internal organ composed of living organisms. Its health and balance matter, not just for digestion, but for emotional well-being.

The Second Brain Within

The gut is often described as having a “second brain,” a term that refers to the enteric nervous system. This intricate network of neurons embedded in the walls of the gastrointestinal tract contains hundreds of millions of nerve cells. It can operate independently of the brain in the skull, controlling digestion, sensing chemical changes, and coordinating muscular contractions.

This second brain does not think in words or images, but it feels. It senses stretch, pressure, nutrient composition, and microbial activity. It communicates constantly with the central nervous system through nerves, hormones, and immune signals. The most famous of these communication pathways is the vagus nerve, a long, wandering nerve that connects the gut to the brainstem.

The existence of the enteric nervous system explains why emotions can be felt physically in the gut. Anxiety can tighten the stomach. Fear can trigger nausea. Calm can bring a sense of warmth and ease in the abdomen. These sensations are not imagined; they are the bodily expression of neural communication between gut and brain.

Microbes as Chemical Messengers

One of the most remarkable discoveries in modern biology is that gut microbes can produce many of the same neurotransmitters used by the human nervous system. These include molecules involved in mood regulation, motivation, and emotional balance.

Serotonin, often associated with happiness and emotional stability, is produced in large quantities in the gut. While most gut-derived serotonin does not cross directly into the brain, it influences local nerve signaling and affects immune cells and blood vessels, indirectly shaping brain function. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to reward and motivation, can also be influenced by microbial activity. Gamma-aminobutyric acid, known for its calming effects on neural activity, is produced by certain bacterial species.

These microbial products act like messages written in a chemical language the body understands. They can stimulate nerve endings, alter hormone release, and influence inflammation. Over time, these signals can affect how the brain responds to stress, processes emotion, and maintains emotional equilibrium.

The Gut–Brain Axis

The term “gut–brain axis” describes the two-way communication system linking the digestive tract and the brain. This axis is not a single pathway but a complex network involving nerves, hormones, immune signaling, and microbial metabolites.

Messages flow upward from gut to brain and downward from brain to gut. Stress, for example, begins in the brain but can alter gut motility, secretion, and microbial composition. In turn, changes in the gut microbiome can influence brain chemistry and behavior. This bidirectional relationship means that mental states can affect digestion, and digestive health can influence mental states.

The gut–brain axis explains why chronic stress can lead to digestive problems and why gastrointestinal disorders are often accompanied by mood disturbances. It also suggests that supporting gut health may be one pathway to supporting emotional well-being.

Inflammation and Emotional Health

Inflammation is a natural and necessary part of the immune response, but when it becomes chronic, it can disrupt many bodily systems, including those involved in mood regulation. The gut microbiome plays a central role in regulating inflammation.

A balanced microbial ecosystem helps maintain the integrity of the gut lining, preventing harmful substances from leaking into the bloodstream. When this barrier is compromised, immune activation can increase, leading to low-grade systemic inflammation. This inflammatory state has been associated with changes in brain function and mood.

Inflammatory signals can influence neurotransmitter metabolism, neural plasticity, and stress hormone regulation. Over time, persistent inflammation may contribute to feelings of fatigue, low motivation, and emotional imbalance. By shaping immune responses, the gut microbiome indirectly shapes emotional landscapes.

Stress, the Gut, and Microbial Balance

Stress does not stay confined to the mind. It ripples through the body, altering hormone levels, immune activity, and nervous system function. The gut is particularly sensitive to stress signals.

When the body perceives stress, it releases hormones that can change gut motility and secretion. These changes can alter the habitat in which microbes live, favoring some species over others. Over time, chronic stress can shift the balance of the microbiome, reducing diversity and altering microbial activity.

This shift can create a feedback loop. Stress alters the microbiome, and an altered microbiome may amplify stress responses through inflammatory or neural pathways. This loop does not mean that stress inevitably damages gut health, but it highlights the deep interconnection between emotional experience and microbial balance.

Development, Early Life, and Emotional Foundations

The relationship between the gut microbiome and mood begins early in life. During infancy and childhood, the microbiome undergoes rapid changes as it responds to diet, environment, and immune development. These early microbial experiences coincide with critical periods of brain development.

Signals from the gut influence the maturation of neural circuits involved in stress response and emotional regulation. Disruptions during this sensitive period, whether from illness, antibiotic exposure, or other factors, can have lasting effects on how the body and brain respond to stress later in life.

This does not imply that early disruptions determine destiny, but it underscores the importance of early biological environments in shaping emotional resilience. The gut microbiome becomes part of the foundation upon which emotional health is built.

Diet as a Bridge Between Mood and Microbes

Food is one of the most powerful influences on the gut microbiome. Every meal is a message to microbial communities, shaping which species thrive and which diminish. Fiber-rich foods, for example, provide fuel for microbes that produce beneficial metabolites. Diets low in diverse nutrients can reduce microbial diversity and alter metabolic output.

The products of microbial metabolism do not remain confined to the gut. They influence immune signaling, hormone regulation, and neural activity. Over time, dietary patterns can shape not only physical health but emotional tone.

This connection helps explain why sustained changes in eating habits can be accompanied by shifts in mood and mental clarity. It also reminds us that nourishment is not merely about calories or nutrients but about feeding an ecosystem that, in turn, feeds us.

Antibiotics and Emotional Side Effects

Antibiotics have saved countless lives by targeting harmful bacteria, but they also affect beneficial microbes. By altering microbial communities, antibiotics can temporarily or, in some cases, more persistently change gut ecology.

Some people experience mood changes during or after antibiotic treatment, including feelings of anxiety or low mood. These effects are not universal, and they vary depending on the individual, the antibiotic, and the duration of treatment. The underlying mechanisms likely involve shifts in microbial signaling, immune activation, and gut–brain communication.

These observations highlight the importance of viewing antibiotics as powerful tools that should be used thoughtfully, with awareness of their broader biological effects.

The Microbiome and Anxiety

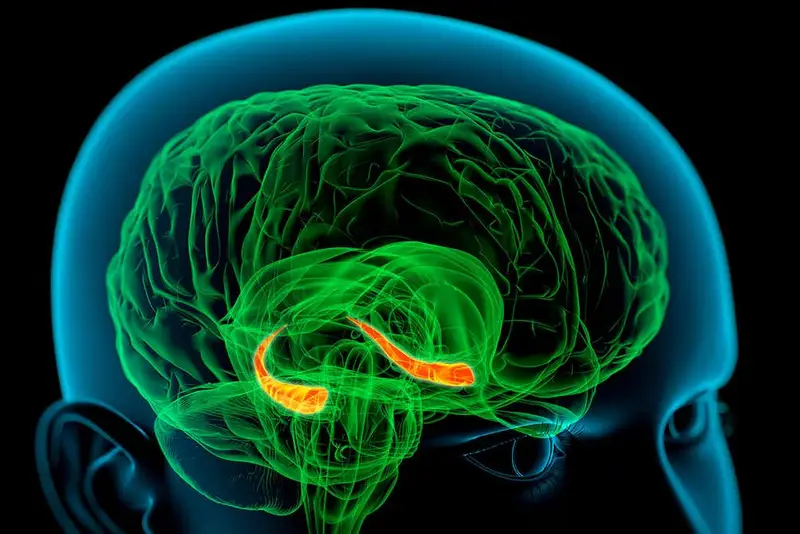

Anxiety is a natural response to perceived threat, but when it becomes chronic or disproportionate, it can disrupt daily life. Research has shown that gut microbes can influence anxiety-related behaviors through multiple pathways.

Microbial metabolites can affect neural circuits involved in fear and stress response. Immune signals originating in the gut can influence brain regions associated with emotional regulation. Changes in microbial diversity can alter stress hormone responses.

This does not mean that anxiety is caused by gut microbes alone. Anxiety arises from a complex interplay of genetics, environment, experience, and biology. The microbiome is one part of this web, influencing how the body and brain respond to stress rather than dictating emotional outcomes.

Depression and the Microbial Connection

Depression is a multifaceted condition involving emotional, cognitive, and physical symptoms. Increasing evidence suggests that gut microbiota may play a role in modulating some of these features.

Altered microbial composition has been associated with changes in inflammatory signaling, neurotransmitter metabolism, and stress hormone regulation, all of which can influence mood. The gut’s influence on sleep, energy levels, and immune function also intersects with depressive symptoms.

Understanding this connection does not reduce depression to a digestive issue. Instead, it expands the biological context, highlighting how interconnected bodily systems contribute to emotional experience.

Individual Differences and Microbial Uniqueness

No two microbiomes are exactly alike. Each person carries a unique microbial signature shaped by genetics, diet, environment, and life history. This individuality means that the gut–mood relationship can vary widely from person to person.

A microbial pattern that supports emotional balance in one individual may not have the same effect in another. This variability challenges simplistic narratives and emphasizes the need for personalized approaches to understanding gut–brain interactions.

It also explains why broad claims about specific microbes or interventions must be interpreted with caution. The microbiome is a dynamic, individualized ecosystem, not a one-size-fits-all solution.

The Role of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

Sleep and gut health are intimately connected. The gut microbiome follows daily rhythms influenced by eating patterns, light exposure, and sleep cycles. Disrupted sleep can alter microbial composition, and microbial signals can, in turn, influence sleep quality.

Sleep deprivation affects stress hormone levels and inflammatory responses, which can impact both mood and gut function. Over time, irregular sleep patterns may contribute to a cycle in which emotional distress and gut imbalance reinforce each other.

Recognizing the role of sleep highlights how lifestyle factors intersect with microbial and emotional health, forming a network of influence rather than isolated causes.

Beyond Reductionism: A Systems Perspective

The science of gut feelings resists simple explanations. It does not reduce mood to microbes or microbes to mood. Instead, it reveals a systems-level interaction in which brain, gut, immune system, and microbiome continuously influence one another.

This perspective challenges the traditional separation between mental and physical health. Emotions are not abstract states floating above the body; they are embodied experiences shaped by biology, environment, and meaning. The gut microbiome becomes part of the biological context within which emotions arise.

Such a view encourages compassion. Emotional struggles are not signs of weakness but reflections of complex biological and experiential processes interacting over time.

The Limits of Current Understanding

While research on the microbiome and mood has grown rapidly, many questions remain unanswered. Much of the evidence comes from animal studies or observational human research. Translating these findings into clear clinical guidance requires careful, ongoing investigation.

Correlation does not equal causation, and the gut–brain relationship is influenced by countless variables. Recognizing these limits is essential to scientific integrity. The excitement surrounding the microbiome should be matched with patience and rigor.

This humility does not diminish the significance of current findings. It ensures that understanding evolves responsibly, guided by evidence rather than hype.

Emotional Meaning and Bodily Wisdom

The phrase “trust your gut” captures a deep intuition about bodily wisdom. While gut feelings are not infallible, they reflect the integration of sensory, emotional, and physiological information. The gut’s sensitivity to internal states allows it to contribute to emotional awareness.

This does not mean that every gut sensation is a message to be followed blindly. Rather, it suggests that the body participates in emotional cognition. Learning to listen to bodily signals with curiosity rather than fear can deepen self-understanding.

The science of gut feelings bridges biology and experience, showing how physical processes contribute to emotional meaning.

A New Way of Seeing Ourselves

Understanding how the microbiome influences mood invites a shift in self-perception. Humans are not solitary organisms but ecosystems, shaped by relationships at every level. Emotional life emerges not from a single organ but from a conversation among many systems.

This perspective fosters humility and wonder. It reminds us that the boundaries of the self are more porous than we once believed. Microbial partners, invisible to the naked eye, participate in shaping how we feel, think, and respond to the world.

The Future of Gut–Mood Science

As research advances, new tools and methods will deepen understanding of gut–brain interactions. Scientists continue to explore how microbial signals interact with neural circuits, how individual differences shape outcomes, and how lifestyle factors modulate these relationships.

The future of this field lies not in simple fixes but in integrated approaches that respect complexity. Emotional health may be supported through attention to diet, stress, sleep, social connection, and physical well-being, all of which influence the microbiome.

This holistic view aligns science with lived experience, acknowledging that emotional balance arises from many interconnected factors.

Listening to the Quiet Conversation Within

The science of gut feelings reveals that the body is always speaking, even when we are not consciously listening. In the quiet rhythms of digestion and the subtle chemistry of microbes, messages flow upward to the brain, shaping emotion and perception.

These messages do not dictate destiny, but they influence the background against which emotional life unfolds. By understanding this inner conversation, we gain a richer appreciation of what it means to feel, to be human, and to live in a body that is both individual and collective.

In the end, gut feelings are not mystical whispers but biological dialogues, grounded in chemistry and connection. They remind us that mood is not just in the mind, and that emotional life is woven from the fabric of the entire living system we call ourselves.