Depression is often spoken about in quiet voices, wrapped in shame, misunderstanding, and fear. For generations, it has been framed as a weakness of character, a failure of will, or simply “sadness taken too far.” Even when modern medicine acknowledged depression as a biological condition, it was largely described as a chemical imbalance in the brain, a disorder of neurotransmitters such as serotonin or dopamine. Yet this explanation, while useful, has always felt incomplete to many who live with depression. Why does depression so often come with physical pain, fatigue, brain fog, and a sense that the entire body is weighed down? Why does it frequently appear alongside chronic illness, stress, infection, or autoimmune disease?

In recent decades, science has begun to explore a powerful and unsettling idea: what if depression is not only a disorder of the mind, but also a disorder of the immune system? What if inflammation, the body’s ancient defense mechanism, plays a central role in shaping mood, motivation, and despair? This question has opened a new frontier in understanding depression, one that connects the immune system and the brain in ways that challenge traditional boundaries between mental and physical health.

This is not a simple story, and it is not a story of replacing one explanation with another. Depression is not “just inflammation,” nor is it purely psychological or purely chemical. It is a deeply complex condition. But the immune–brain connection has revealed that the body and mind are far more intertwined than we once believed, and that depression may, in many cases, be partly an inflammatory disease.

The Ancient Purpose of Inflammation

To understand the link between depression and inflammation, we must first understand what inflammation is and why it exists. Inflammation is not an enemy. It is one of the body’s most essential survival tools. When the immune system detects injury or infection, it releases chemical messengers called cytokines. These molecules coordinate a defensive response, increasing blood flow, recruiting immune cells, and triggering behaviors that promote healing.

When you have the flu, you feel tired, achy, withdrawn, and mentally slow. You lose interest in social interaction and pleasurable activities. You want to rest, sleep, and be left alone. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. Conserving energy and avoiding danger increases the chance of recovery. This collection of symptoms is known as sickness behavior, and it is driven largely by inflammation.

The striking thing is how closely sickness behavior resembles depression. Low mood, fatigue, reduced motivation, cognitive slowing, loss of pleasure, social withdrawal, and disrupted sleep are core features of both states. This overlap has led scientists to ask a provocative question: could depression, in some cases, be a maladaptive or prolonged form of the brain’s response to inflammation?

The Immune System and the Brain Are in Constant Conversation

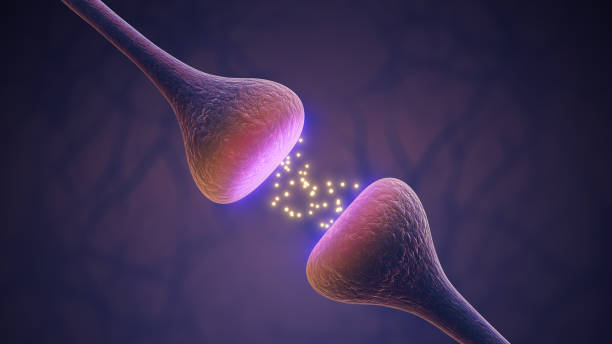

For a long time, the brain was thought to be immune-privileged, sealed off from the immune system by the blood–brain barrier. This view has changed dramatically. We now know that the immune system and the brain are in constant communication. Cytokines released in the body can influence brain function directly or indirectly. Immune cells can signal the brain through the bloodstream, through the vagus nerve, and through specialized regions where the blood–brain barrier is more permeable.

Microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, play a crucial role in this dialogue. These cells monitor the brain environment, prune synapses, respond to injury, and release inflammatory signals when activated. In healthy conditions, microglia support learning, memory, and neural plasticity. But when they become chronically activated, they can alter brain circuits involved in mood, motivation, and cognition.

Inflammation can affect neurotransmitter systems long associated with depression. It can reduce the availability of serotonin by altering its metabolism. It can interfere with dopamine signaling, dampening motivation and pleasure. It can disrupt glutamate balance, leading to neural toxicity and cognitive dysfunction. Inflammation can also impair neurogenesis, the birth of new neurons, particularly in the hippocampus, a brain region deeply involved in mood regulation and memory.

This is not speculation. These mechanisms have been observed repeatedly in both animal and human studies. The immune system does not merely influence the brain from the outside; it shapes the very processes that underlie emotion and thought.

Evidence Linking Inflammation and Depression

One of the strongest pieces of evidence for the inflammatory hypothesis of depression comes from clinical observation. People with chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and multiple sclerosis, have much higher rates of depression than the general population. This increased risk cannot be explained solely by psychological stress or disability. Even when disease severity is controlled, depression remains more common.

Similarly, patients treated with immune-activating therapies offer a revealing window into the immune–brain connection. Interferon-alpha, a medication used to treat certain viral infections and cancers, is known to induce depression in a significant proportion of patients. These individuals often develop depressive symptoms despite having no prior history of mood disorders. When the treatment stops, the depression often resolves.

Blood studies have consistently shown that many people with depression have elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and pro-inflammatory cytokines. This is not true for everyone with depression, but it is true for a substantial subgroup. Importantly, higher inflammation levels are often associated with more severe symptoms, poorer response to traditional antidepressants, and greater physical complaints.

Brain imaging studies add another layer of evidence. Increased activation of microglia has been observed in people with major depressive disorder, particularly in those who have experienced chronic stress or childhood trauma. These findings suggest that inflammation is not just a peripheral phenomenon but is occurring within the brain itself.

Stress as an Inflammatory Trigger

One of the most powerful links between depression and inflammation is stress. Psychological stress is not merely an abstract mental experience; it is a biological event. When the brain perceives threat, it activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, releasing stress hormones such as cortisol. In short bursts, this response is adaptive. But when stress becomes chronic, it can dysregulate immune function.

Chronic stress promotes a state of low-grade inflammation. It alters immune cell behavior, making them more likely to release pro-inflammatory cytokines. At the same time, stress can reduce the body’s sensitivity to cortisol, weakening its anti-inflammatory effects. The result is an immune system that is more reactive and less well-controlled.

This helps explain why early life adversity, such as childhood neglect, abuse, or prolonged insecurity, is so strongly linked to depression later in life. These experiences can “program” the immune system toward a pro-inflammatory state that persists for decades. Depression, in this context, may be the psychological expression of a body that has learned to expect danger.

Depression Is Not One Disease

One of the most important insights from inflammation research is that depression is not a single, uniform condition. It is a syndrome, a collection of symptoms that can arise from different underlying biological pathways. Inflammation appears to be a major driver in some individuals but not others.

This helps explain why antidepressants work well for some people and poorly for others. Traditional antidepressants primarily target neurotransmitter systems. If a person’s depression is driven largely by inflammation, these medications may have limited effectiveness. Studies have shown that people with higher inflammatory markers are less likely to respond to standard antidepressant treatment.

This does not mean that antidepressants are ineffective or misguided. It means that depression is heterogeneous, and that a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate. Recognizing inflammatory depression as a subtype opens the door to more personalized and compassionate treatment strategies.

The Role of the Gut in Immune–Brain Communication

The gut is emerging as a central player in the immune–brain connection. The digestive tract is home to trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiome. These microbes are not passive passengers. They interact constantly with the immune system, producing metabolites that influence inflammation and brain function.

Disruptions in the gut microbiome, known as dysbiosis, have been linked to increased inflammation and depressive symptoms. Stress, poor diet, infection, and antibiotic use can all alter the microbial balance, weakening the gut barrier and allowing inflammatory signals to enter the bloodstream.

The gut communicates with the brain through immune pathways, neural pathways, and hormonal signals. This bidirectional communication means that changes in gut health can affect mood, and changes in mood can affect gut health. Depression, inflammation, and digestive problems often form a reinforcing loop that can be difficult to break.

Inflammation and the Subjective Experience of Depression

Understanding depression as partly inflammatory helps explain why it feels the way it does. People with depression often describe a sense of heaviness, as if their body is made of lead. They experience exhaustion that sleep does not relieve, mental fog that dulls thinking, and a loss of pleasure that feels physical rather than emotional.

Inflammation affects energy metabolism, reducing the efficiency of cellular processes. It alters sleep regulation, disrupts circadian rhythms, and increases sensitivity to pain. It can make the world feel slower, more distant, and more demanding. From the inside, depression often feels less like sadness and more like being unwell.

This perspective challenges the harmful idea that people with depression should simply “try harder” or “think positively.” If inflammation is involved, then depression is not a failure of effort or attitude. It is a state of altered biology that deserves care, understanding, and treatment.

Anti-Inflammatory Approaches to Depression

The recognition of inflammation’s role in depression has sparked interest in anti-inflammatory treatments. Some studies suggest that anti-inflammatory medications can reduce depressive symptoms, particularly in individuals with elevated inflammatory markers. Lifestyle interventions that reduce inflammation, such as improved sleep, regular physical activity, and balanced nutrition, have also shown benefits.

Exercise is particularly powerful, not because it is easy, but because it modulates immune function, increases anti-inflammatory cytokines, and enhances neuroplasticity. When depression makes movement feel impossible, this creates a cruel paradox. Understanding the biological barriers can help clinicians and patients approach exercise with compassion rather than guilt.

Psychotherapy also interacts with inflammation in meaningful ways. Reducing stress, processing trauma, and building social connection can lower inflammatory signaling over time. The mind and immune system influence each other in both directions, reinforcing the idea that treatment should address both psychological and biological dimensions.

The Risks of Oversimplification

While the inflammatory hypothesis of depression is compelling, it must be approached with care. Not all depression is inflammatory, and inflammation is not the sole cause of mood disorders. Reducing depression to a single mechanism risks replacing one incomplete model with another.

Inflammation interacts with genetics, environment, hormones, neural circuits, and personal history. It is one piece of a vast puzzle. Moreover, inflammation itself can be both cause and consequence of depression. Low mood can promote behaviors that increase inflammation, such as poor sleep, social isolation, and physical inactivity.

Scientific accuracy demands nuance. The immune–brain connection does not invalidate psychological explanations of depression; it enriches them. It shows that emotional pain is embodied, and that biology and experience are inseparable.

A Shift in How We Think About Mental Illness

Viewing depression through an immune lens has profound implications for stigma. It blurs the artificial boundary between mental and physical illness. If depression involves inflammation, then it is as real and measurable as any other medical condition.

This perspective can bring relief to those who have blamed themselves for their suffering. It can also encourage healthcare systems to integrate mental and physical care rather than treating them as separate domains.

At the same time, it invites a deeper ethical responsibility. If social conditions such as poverty, discrimination, and chronic stress contribute to inflammation and depression, then mental health is not just an individual issue but a societal one. Biology reflects the world we create.

The Future of Depression Research

The study of inflammation and depression is still evolving. Researchers are working to identify reliable biomarkers that can distinguish inflammatory subtypes of depression. Advances in neuroimaging, immunology, and genetics are bringing greater clarity to the immune–brain interface.

Future treatments may involve tailored approaches that combine antidepressants, anti-inflammatory strategies, psychotherapy, and lifestyle interventions based on individual biology. This vision moves away from trial-and-error prescribing toward precision psychiatry.

Yet even as science advances, one truth remains central: depression is a human experience, not just a biological state. Inflammation may shape mood, but meaning, connection, and hope shape recovery.

Rethinking Healing

If depression is partly an inflammatory disease, healing may require more than symptom suppression. It may require restoring balance to systems that have been pushed beyond their limits. This includes not only immune balance but emotional safety, social belonging, and a sense of purpose.

Healing does not mean eliminating all inflammation. It means helping the body and brain return to a state where defensive responses are no longer dominating experience. It means addressing stressors that keep the immune system on constant alert.

This understanding encourages patience. Inflammation builds slowly, and it often recedes slowly. Recovery may not be immediate, but it is possible.

Conclusion: A More Compassionate Understanding of Depression

So, is depression an inflammatory disease? The most accurate answer is that depression can be, in part, an inflammatory condition for many people. It is not always, and it is never only that. But recognizing the immune–brain connection deepens our understanding of why depression feels so profoundly physical, why it is often resistant to simple solutions, and why compassion is not optional but essential.

Depression is not a personal failure. It is not a lack of gratitude or strength. It is a complex interplay of brain, body, and life experience. Inflammation is one of the threads woven into this tapestry, reminding us that the mind lives in the body, and the body carries the story of our lives.

By embracing this integrated view, we move closer to a future where depression is met not with judgment or reductionism, but with curiosity, care, and scientifically grounded hope.