Optogenetics sounds like science fiction, a word that seems to belong to futuristic novels rather than real laboratories. Yet it is one of the most powerful and transformative scientific tools ever developed to understand the brain. At its core, optogenetics allows scientists to control the activity of specific brain cells using light. With extraordinary precision, neurons can be switched on or off in living brains, revealing how thoughts, emotions, memories, and behaviors arise. This is not magic. It is the result of decades of careful biological discovery, genetic engineering, physics, and neuroscience converging into a single revolutionary approach.

To appreciate optogenetics, one must first appreciate the challenge it addresses. The brain is unimaginably complex. It contains billions of neurons, each connected to thousands of others, communicating through electrical signals and chemical messengers. Every thought, movement, feeling, and memory emerges from this vast network. For centuries, scientists struggled to understand how specific brain cells contribute to specific functions. Traditional tools could observe brain activity or broadly stimulate regions, but they lacked precision. Optogenetics changed this forever by giving researchers something they had never truly had before: the ability to control defined neurons, at precise moments in time, inside a living brain.

The Brain as an Electrical Organ

The story of optogenetics begins with the recognition that the brain is an electrical system. Neurons communicate using electrical impulses called action potentials. These impulses travel along neurons and trigger the release of chemical signals at synapses, allowing neurons to talk to one another. This electrical nature of the brain was discovered in the nineteenth century and refined over generations of research.

Understanding that neurons are electrically active suggested that controlling electricity could influence brain function. Early neuroscientists used electrodes to stimulate the brain, sometimes producing movements, sensations, or emotional responses. These experiments were groundbreaking, but they were also crude. Electrodes stimulate many cells at once, including different types of neurons and fibers passing through the area. The brain, however, is not organized simply by location. Different cell types, intermingled in the same region, can play very different roles. Stimulating them all together blurs the picture rather than clarifying it.

The dream of neuroscience became clear: to control specific neurons, and only those neurons, with perfect timing. Optogenetics emerged as the tool that turned this dream into reality.

Light as a Biological Tool

Light has long fascinated scientists as a way to study and influence living systems. Microscopy uses light to reveal cellular structures. Imaging techniques use light to monitor activity inside tissues. But using light to control cells required a crucial insight: cells would need to respond directly to light in a predictable way.

Nature had already solved this problem. Many organisms, from bacteria to algae, contain light-sensitive proteins that allow them to respond to sunlight. These proteins, called opsins, change their shape when exposed to light, triggering biological processes. In some microorganisms, opsins control the flow of ions across the cell membrane, effectively turning light into an electrical signal.

The realization that such proteins existed was a turning point. If these light-sensitive proteins could be introduced into neurons, then neurons could be controlled by light. This idea was elegant and bold, combining genetics, optics, and neuroscience into a single approach. It was the conceptual birth of optogenetics.

The Genetic Foundation of Optogenetics

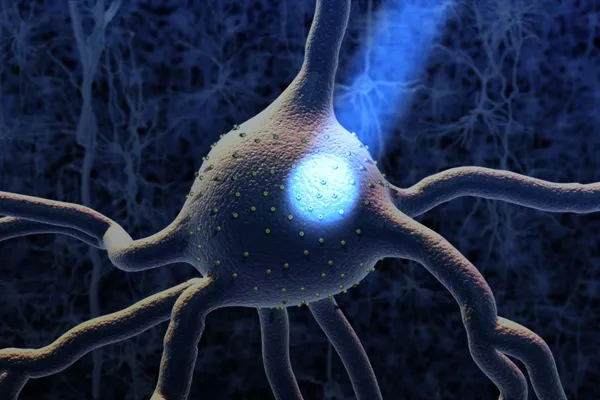

Optogenetics relies fundamentally on genetics. Neurons do not naturally respond to light in a way that allows precise control of electrical activity. To change this, scientists use genetic techniques to introduce genes encoding light-sensitive proteins into specific neurons.

These genes act as instructions, telling neurons to produce opsins and insert them into their membranes. Once expressed, the neuron becomes light-sensitive. When light of the appropriate wavelength is delivered, the opsin opens or closes ion channels, changing the electrical state of the neuron. Depending on the type of opsin used, the neuron can be activated or silenced.

This genetic targeting is what gives optogenetics its extraordinary specificity. By using genetic markers, scientists can restrict opsin expression to particular types of neurons, defined by their molecular identity, connections, or role in behavior. This precision allows researchers to ask questions that were previously impossible to answer.

Timing and Precision Beyond Imagination

One of the most remarkable features of optogenetics is its temporal precision. Neurons operate on the scale of milliseconds, and optogenetics can match this speed. Light can be turned on and off almost instantaneously, allowing researchers to control neuronal activity with exquisite timing.

This matters deeply because brain function depends not just on which neurons are active, but when they are active. Timing determines whether signals reinforce each other, cancel out, or trigger downstream effects. Optogenetics allows scientists to probe this temporal dimension directly, revealing how patterns of activity give rise to perception and behavior.

The precision of optogenetics stands in stark contrast to older techniques, such as pharmacological manipulation, which can take minutes or hours to take effect and affect many cell types simultaneously. Light-based control offers a level of clarity that transformed neuroscience almost overnight.

Seeing Causation, Not Just Correlation

Before optogenetics, much of neuroscience relied on correlation. Researchers could observe that certain neurons were active during a behavior, but they could not easily test whether those neurons caused the behavior. Correlation alone cannot establish causation.

Optogenetics changed this by allowing direct causal tests. By activating a specific group of neurons, scientists can observe whether a behavior is triggered. By silencing those neurons, they can see whether the behavior disappears. This ability to intervene, rather than merely observe, revolutionized the field.

Suddenly, abstract questions about the neural basis of memory, fear, movement, and decision-making became experimentally accessible. Optogenetics turned the brain from a passive object of study into an interactive system that could be probed with precision and intent.

Optogenetics and the Study of Behavior

One of the most emotionally compelling aspects of optogenetics is its application to behavior. In animal models, researchers have used light to trigger movements, induce fear or calm, alter feeding behavior, and even influence social interactions. These experiments are striking not because they are sensational, but because they reveal how deeply behavior is rooted in neural circuits.

When a beam of light can cause an animal to freeze in fear or seek a reward, it underscores the biological basis of emotion and motivation. This does not reduce human experience to mere mechanics, but it deepens our understanding of how physical processes give rise to subjective states.

Optogenetics allows scientists to map circuits underlying complex behaviors, showing how different populations of neurons cooperate or compete to shape actions. These insights are reshaping how we think about the brain as a dynamic, distributed system rather than a collection of isolated parts.

Memory, Learning, and the Engram

Memory has long been one of neuroscience’s greatest mysteries. How does the brain store experiences? How are memories retrieved? Optogenetics has provided unprecedented tools to explore these questions.

Research suggests that memories are stored in specific populations of neurons, often referred to as memory traces or engrams. Optogenetics allows scientists to label neurons active during a learning experience and later reactivate them with light. In doing so, they can trigger the recall of a memory even in the absence of the original stimulus.

These experiments are emotionally powerful because they demonstrate that memory has a physical basis in identifiable cells. At the same time, they raise profound philosophical questions about identity, experience, and the nature of self. Optogenetics does not answer these questions fully, but it grounds them in biological reality.

Optogenetics and Emotional Circuits

Emotions are among the most complex and deeply human aspects of brain function. Fear, joy, sadness, and desire are not localized to single brain regions but emerge from interactions among many circuits. Optogenetics has provided tools to dissect these circuits with unprecedented clarity.

By selectively controlling neurons involved in emotional processing, researchers can observe how emotions are generated and regulated. This has led to new insights into anxiety, depression, and stress-related disorders. Understanding which circuits promote resilience and which contribute to vulnerability could guide future treatments.

These studies also reveal that emotions are not fixed states but dynamic processes shaped by neural activity patterns. Optogenetics allows scientists to explore these dynamics in real time, deepening our understanding of emotional life.

The Promise for Mental Health Research

Mental health disorders affect millions of people worldwide, often with devastating consequences. Despite their prevalence, many psychiatric conditions remain poorly understood at the neural level. Optogenetics offers a powerful approach to uncovering the circuit-level mechanisms underlying these disorders.

By modeling aspects of mental illness in animals and using optogenetics to manipulate relevant circuits, researchers can test hypotheses about causation and intervention. This does not mean that optogenetics itself will be used directly as a therapy in humans in its current form, but the knowledge gained can inform the development of new treatments.

The emotional weight of this research is significant. Each insight brings hope that suffering rooted in brain dysfunction can be better understood and alleviated. Optogenetics represents not just a technical advance, but a compassionate one, driven by the desire to reduce human suffering.

Technical Challenges and Ethical Reflections

Despite its power, optogenetics is not without challenges. Delivering light to deep brain structures requires invasive methods, such as implanted optical fibers. Genetic modification raises ethical questions, especially when considering potential future applications in humans.

These challenges force careful reflection. Optogenetics is primarily a research tool, not a clinical treatment. Its use demands strict ethical oversight, transparency, and respect for animal welfare. Scientists must balance the pursuit of knowledge with responsibility and humility.

Ethical reflection is not a limitation but a strength. It ensures that optogenetics is developed thoughtfully, with attention to its broader implications for society and humanity.

Optogenetics and the Philosophy of Free Will

The ability to control neurons with light inevitably raises questions about free will and agency. If behavior can be altered by activating specific neurons, what does that say about choice and responsibility?

Optogenetics does not negate free will, but it challenges simplistic notions of it. It reveals that choices emerge from neural processes shaped by biology, experience, and context. Understanding these processes does not diminish human dignity; it enriches our understanding of ourselves.

By showing how neural circuits influence behavior, optogenetics invites a more compassionate view of human action, one that recognizes the deep biological roots of behavior without denying personal meaning or moral responsibility.

Integration with Other Neuroscience Tools

Optogenetics does not stand alone. Its true power emerges when combined with other techniques such as brain imaging, electrophysiology, and computational modeling. Together, these approaches provide a multi-dimensional view of brain function.

By combining optogenetics with imaging, researchers can observe how manipulating one set of neurons affects activity across the brain. This systems-level perspective is essential for understanding the brain as an integrated whole rather than a collection of parts.

The integration of optogenetics with other tools represents the future of neuroscience, where precise intervention and comprehensive observation work hand in hand.

The Human Story Behind the Science

Optogenetics is not just a technological achievement; it is a human story of creativity, persistence, and collaboration. Scientists from different disciplines contributed insights that made it possible. Biologists studied light-sensitive proteins. Geneticists developed methods to target specific cells. Physicists refined optical techniques. Neuroscientists asked bold questions about brain function.

This interdisciplinary spirit reflects the best of science. Optogenetics emerged not from a single moment of genius, but from decades of incremental progress driven by curiosity and cooperation.

Behind every experiment are human beings grappling with uncertainty, driven by wonder, and motivated by the desire to understand the mind.

Optogenetics and the Future of Brain Science

The future of optogenetics is rich with possibility. New opsins are being developed with improved properties, allowing finer control and deeper penetration. Advances in light delivery and genetic targeting continue to expand the technique’s reach.

As optogenetics evolves, it will likely play a central role in unraveling some of neuroscience’s greatest mysteries. How does consciousness arise? How are complex decisions made? How does the brain integrate perception, emotion, and action into a coherent experience?

While optogenetics alone will not answer all these questions, it will remain an essential part of the scientific toolkit that brings us closer to understanding ourselves.

Light as a Symbol and a Tool

There is poetic beauty in the idea of using light to understand the brain. Light has long symbolized knowledge, insight, and clarity. In optogenetics, this symbolism becomes literal. Light illuminates the inner workings of the mind, revealing patterns hidden in darkness.

This union of metaphor and mechanism captures the emotional essence of optogenetics. It is science that not only explains but inspires, bridging the gap between cold precision and human wonder.

Optogenetics and the Meaning of Understanding

Ultimately, optogenetics invites us to reflect on what it means to understand the brain. Understanding does not mean reducing experience to equations, but connecting levels of explanation, from molecules to thoughts.

Optogenetics shows that complex mental phenomena arise from physical processes that can be studied, manipulated, and understood. This does not strip life of meaning. Instead, it reveals that meaning emerges from the intricate dance of neurons shaped by evolution and experience.

In this sense, optogenetics deepens rather than diminishes the mystery of being human.

Conclusion: A New Way of Touching the Mind

Optogenetics stands as one of the most remarkable achievements in modern science. By allowing precise control of brain cells with light, it has transformed neuroscience from an observational discipline into an experimental one capable of testing causation at the level of circuits.

Its impact extends beyond laboratories. It reshapes how we think about behavior, emotion, memory, and identity. It offers hope for understanding and treating mental illness. It challenges philosophical assumptions while grounding them in biology.

Most of all, optogenetics reminds us of the power of human curiosity. By asking bold questions and daring to merge disciplines, scientists found a way to touch the mind with light. In doing so, they illuminated not only the brain, but the enduring human desire to understand ourselves.