Late at night, when the world grows quiet and the body longs for rest, millions of small glowing rectangles remain awake. Smartphones illuminate faces in dark rooms, casting a cool, bluish light that feels harmless, even comforting. A message arrives. A video auto-plays. Time slips by unnoticed. Yet beneath this familiar ritual, something profound is happening inside the brain. A delicate biological signal is being disrupted, a signal that has guided human sleep for thousands of years. This signal is melatonin, and blue light from smartphones has become one of its most persistent enemies.

Melatonin is not just another chemical in the body. It is the hormone of night, the molecular whisper that tells the brain it is safe to rest. When melatonin flows freely, the body relaxes, thoughts slow, and sleep arrives naturally. When melatonin is suppressed, sleep becomes fragile, shallow, or elusive. Blue light, especially the kind emitted by smartphone screens, interferes with this process at its source, confusing the brain into believing that night is day.

Understanding how this happens requires a journey into biology, neuroscience, evolution, and modern technology. It is a story about how ancient rhythms collide with modern habits, and how a tiny wavelength of light can reshape human sleep, health, and emotional balance.

Melatonin and the Architecture of Sleep

Melatonin is produced deep within the brain by a small structure called the pineal gland. Its release follows a daily rhythm known as the circadian rhythm, an internal clock that cycles roughly every twenty-four hours. This clock is not set by alarm clocks or schedules, but by light itself. For most of human history, the sun governed this rhythm with absolute authority.

As daylight fades in the evening, melatonin production begins to rise. This increase does not knock a person unconscious, but it gently shifts the body toward rest. Body temperature drops slightly. Alertness softens. Muscles relax. The mind becomes more reflective and less reactive. This hormonal transition prepares the brain for sleep long before the head touches the pillow.

Melatonin does more than initiate sleep. It helps regulate the timing of sleep stages, supports deep restorative sleep, and communicates with other hormonal systems involved in immunity, metabolism, and mood. It is deeply woven into the body’s internal harmony. When melatonin is disrupted, sleep is not the only thing that suffers.

The Eye as a Gateway to the Brain

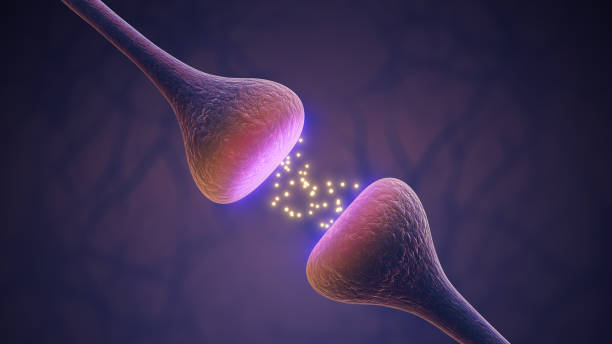

To understand how blue light interferes with melatonin, one must first understand how light enters the brain. The eyes are not merely organs of vision. They are also sensors that inform the brain about the time of day. Specialized cells in the retina detect light and send signals directly to the brain’s master clock, a region known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus.

Among these retinal cells are photosensitive ganglion cells that respond most strongly to blue wavelengths of light. These cells do not help form images. Instead, they act as biological timekeepers. When they detect blue light, they signal that it is daytime, regardless of the actual hour.

This system evolved for survival. Blue light is abundant in natural daylight, especially in the morning and midday sky. Its presence signals alertness, activity, and opportunity. Its absence after sunset signals safety, rest, and recovery. For most of human evolution, artificial blue light simply did not exist at night.

Blue Light and the Modern Night

Smartphones, tablets, and LED screens emit light rich in blue wavelengths. This design is not accidental. Blue light increases clarity, contrast, and brightness, making screens easier to read and visually engaging. During the day, this can be beneficial. At night, it becomes disruptive.

When a smartphone screen lights up after sunset, the retina receives a powerful blue light signal. The photosensitive cells respond as they were designed to, sending a message to the brain’s master clock that it is still daytime. In response, the brain suppresses melatonin production. The night signal is delayed or weakened.

This suppression can happen quickly. Even short exposure to blue light in the evening can reduce melatonin levels. Longer exposure, especially close to bedtime, can delay melatonin release by hours. The brain becomes trapped in a false twilight, unsure whether it is time to rest or remain alert.

The Illusion of Wakefulness

One of the most deceptive aspects of blue light exposure is how it feels. People often believe they are relaxing while scrolling through their phones at night. The body is still, the environment is quiet, and the activity feels passive. Yet biologically, the brain is being stimulated.

Blue light increases alertness by reducing melatonin and influencing other neurotransmitters involved in attention. This creates a paradoxical state: mental stimulation combined with physical stillness. The mind becomes active while the body remains motionless, a combination that confuses the nervous system.

This illusion of relaxation can delay sleep onset without the person realizing it. Minutes turn into hours. When the phone is finally set aside, sleep does not arrive easily. The brain has been told, repeatedly, that it is still daytime.

Circadian Rhythm Disruption

Melatonin suppression does not merely affect one night of sleep. Repeated exposure to blue light at night can shift the entire circadian rhythm. The internal clock begins to run late, pushing sleep and wake times later into the night and morning.

This shift has consequences. Waking up becomes harder. Morning alertness decreases. The natural peak of cognitive performance moves to later hours, often clashing with social and work schedules. This mismatch between internal time and external demands creates chronic sleep deprivation, even if total time in bed appears adequate.

Over time, the circadian rhythm can become fragmented. Melatonin release may become weaker or irregular. Sleep becomes lighter, more easily disturbed. The body loses its clear sense of night and day.

The Emotional Cost of Melatonin Loss

Melatonin is closely linked to emotional regulation. Healthy sleep supports mood stability, resilience to stress, and emotional clarity. When melatonin production is disrupted, these functions suffer.

People exposed to excessive blue light at night often report increased irritability, anxiety, and low mood. These emotional changes are not simply psychological reactions to poor sleep. They are also biological consequences of altered neurochemistry.

Melatonin interacts with serotonin, dopamine, and cortisol, hormones and neurotransmitters that shape mood and stress response. When melatonin is suppressed, cortisol levels may remain elevated at night, keeping the body in a state of subtle stress. This can lead to racing thoughts, emotional restlessness, and difficulty unwinding.

Sleep Quality and the Depth of Rest

Even when sleep occurs after blue light exposure, its quality is often compromised. Melatonin plays a key role in coordinating sleep stages, particularly deep sleep. Deep sleep is essential for physical repair, immune function, and memory consolidation.

Reduced melatonin can shorten deep sleep phases, leading to more fragmented and lighter sleep. People may wake frequently during the night or feel unrefreshed in the morning despite spending sufficient time in bed.

This erosion of sleep depth accumulates over time. The body enters a state of chronic under-recovery, where rest never fully restores energy. Fatigue becomes a constant background presence.

The Developing Brain and Blue Light

The impact of blue light on melatonin is particularly concerning for children and adolescents. Younger brains are more sensitive to light, and melatonin plays a crucial role in development.

During adolescence, natural circadian rhythms already shift later, a biological change that makes teenagers naturally inclined to stay up late. Blue light exposure at night amplifies this shift, delaying sleep even further. Early school start times then force early waking, creating chronic sleep deprivation.

This lack of sleep affects attention, learning, emotional regulation, and mental health. It is not merely a matter of tiredness, but of altered brain development during critical years.

Evolutionary Mismatch

From an evolutionary perspective, blue light at night represents a profound mismatch between biology and environment. Human circadian systems evolved under conditions where night was dark, illuminated only by firelight and moonlight, both low in blue wavelengths.

Firelight is rich in warm, reddish tones that do not strongly suppress melatonin. Moonlight is faint and insufficient to override night signals. For thousands of generations, darkness reliably signaled rest.

In the span of a single century, artificial lighting has transformed the night. Smartphones represent the most intimate and intense form of this transformation, placing bright blue light inches from the eyes at precisely the time when darkness is biologically required.

The Brain’s Confusion Between Day and Night

The brain does not understand calendars or clocks. It understands light. When light signals are inconsistent, the brain becomes confused. A brightly lit screen at midnight sends the same signal as a sunny morning.

This confusion affects not only sleep but metabolism, hormone regulation, and immune function. Many bodily processes follow circadian rhythms coordinated by melatonin. When these rhythms are disrupted, the effects ripple outward through the entire system.

Over time, this confusion can contribute to broader health issues. While melatonin suppression alone is not the sole cause of these problems, it plays a significant role in destabilizing the body’s internal balance.

Psychological Attachment to the Screen

Beyond biology, there is a psychological dimension to smartphone use at night. The phone is not just a source of light; it is a source of connection, information, and distraction. For many people, it fills emotional gaps, alleviates boredom, or quiets anxiety.

This attachment makes it difficult to disconnect, even when the body signals exhaustion. The glowing screen becomes a companion in the dark, offering endless stimulation at the expense of rest.

The combination of emotional engagement and blue light creates a powerful barrier to melatonin release. The brain remains alert not only because of light, but because of meaning, novelty, and anticipation.

Nighttime Alertness and the False Second Wind

Many people experience a “second wind” late at night, a surge of alertness that seems to contradict fatigue. Blue light plays a role in this phenomenon. By suppressing melatonin, it delays the body’s natural descent into sleepiness.

This second wind can be misleading. It encourages further screen use, pushing bedtime later and later. Eventually, exhaustion returns, but often at a time incompatible with responsibilities the next day.

This cycle reinforces itself, creating a pattern of delayed sleep, insufficient rest, and reliance on stimulants during the day to compensate.

Long-Term Health Implications

Chronic melatonin suppression does not remain confined to sleep. Melatonin influences immune function, acting as an antioxidant and supporting nighttime repair processes. Reduced melatonin may weaken these protective effects over time.

Melatonin also interacts with metabolic hormones that regulate appetite and glucose balance. Disrupted circadian rhythms have been associated with weight gain and metabolic imbalance, partly due to altered hormonal signaling.

While smartphones alone are not responsible for these complex conditions, their role in nighttime blue light exposure is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor.

Cultural Normalization of Sleeplessness

Modern culture often glorifies productivity, availability, and constant connectivity. Being reachable at all hours is treated as normal, even admirable. Sleep, by contrast, is sometimes viewed as negotiable or expendable.

This cultural attitude amplifies the biological impact of blue light. When late-night screen use is normalized, melatonin suppression becomes widespread and habitual. The consequences are experienced individually but generated collectively.

Reclaiming healthy sleep requires not only personal choices but a cultural shift in how rest is valued.

The Subtlety of Damage

One of the most insidious aspects of blue light’s effect on melatonin is its subtlety. There is no immediate pain, no obvious warning sign. The damage accumulates quietly, night after night.

People may adapt to feeling tired, irritable, or unfocused, accepting these states as normal. The connection to nighttime screen use may go unnoticed. Melatonin loss becomes invisible, its absence felt only through its consequences.

Relearning Darkness

Darkness is not the enemy it is often portrayed to be. Biologically, darkness is a signal of safety, rest, and restoration. Allowing darkness in the evening supports melatonin production and honors the body’s natural rhythms.

Reducing blue light exposure at night is not about rejecting technology, but about using it wisely. The human brain was not designed to stare into artificial suns after sunset.

Creating space for darkness allows melatonin to rise, inviting sleep not as a struggle, but as a natural transition.

The Emotional Relief of Restored Sleep

When melatonin production is allowed to recover, the effects can be profound. Sleep becomes deeper and more refreshing. Mood stabilizes. Anxiety softens. Mornings feel less punishing.

These changes are not dramatic or instant, but they are deeply felt. They remind the body of a rhythm it never forgot, only lost.

Restored melatonin does not merely improve sleep; it restores a sense of alignment between body, mind, and environment.

A Choice Between Light and Night

The story of blue light and melatonin is ultimately a story of choice. Modern technology offers unprecedented access to information and connection, but it also challenges ancient biological systems.

Each night presents a quiet decision: to continue feeding the brain daylight signals or to allow night to arrive fully. This decision shapes not only sleep, but health, mood, and quality of life.

Melatonin is fragile, but it is also resilient. Given the right conditions, it returns. The body remembers how to sleep. The night remembers how to heal.

Returning to the Rhythm of Being Human

Humans are diurnal creatures, shaped by the rising and setting of the sun. Blue light from smartphones blurs this fundamental rhythm, erasing the boundary between day and night.

Understanding how this light destroys melatonin production is not about fear, but awareness. It is an invitation to live in harmony with biology rather than in conflict with it.

In choosing darkness at night, we do not lose anything essential. We gain rest, clarity, and a deeper connection to the rhythms that have guided life for millennia.