Depression is often spoken about as sadness, emptiness, or a loss of interest in life, but beneath these lived experiences lies a complex and deeply human biological story. Depression is not simply a weakness of character, a failure of will, or a passing mood. It is a condition rooted in the chemistry of the brain, shaped by genes, environment, experience, and time. To understand the chemistry of depression is not to reduce human suffering to molecules, but to recognize how profoundly the body and mind are connected.

The brain is not separate from emotion. Feeling is biology in motion. Every thought, memory, and mood emerges from chemical signals moving through neural networks that evolved to keep us alive. Depression arises when these systems, designed for balance and adaptation, become dysregulated. The result is not just sadness, but a shift in perception, energy, motivation, and even physical sensation. Chemistry does not erase the personal meaning of depression; it explains how deeply real it is.

The Brain as a Chemical Organ

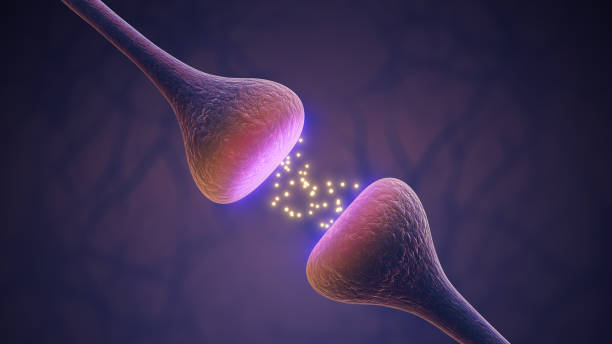

The human brain is often described as an electrical organ, but electricity is only part of the story. The true language of the brain is chemical. Neurons communicate with one another by releasing molecules called neurotransmitters into tiny gaps known as synapses. These chemicals bind to receptors on neighboring cells, triggering cascades of activity that shape mood, thought, and behavior.

This chemical communication is astonishingly precise. A slight change in concentration, timing, or receptor sensitivity can alter how the brain functions. Depression emerges not from a single chemical failure, but from subtle shifts across multiple systems. It is a network problem, not a single broken part.

The chemistry of the brain is dynamic, constantly adapting to experience. Stress, trauma, loss, and chronic adversity can reshape chemical signaling over time. Depression is often the result of this long conversation between biology and life.

Neurotransmitters and the Myth of Simple Imbalance

For many years, depression was popularly explained as a “chemical imbalance,” especially involving serotonin. While this idea helped reduce stigma by emphasizing biology, it oversimplified a far more intricate reality. Neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine do play crucial roles in mood regulation, but depression cannot be explained by low levels of a single chemical.

Serotonin influences mood, sleep, appetite, and emotional regulation. Dopamine is central to motivation, pleasure, and reward. Norepinephrine shapes alertness, energy, and stress responses. In depression, these systems often function differently, but not always in the same way from person to person. Some individuals may have altered signaling rather than reduced levels. Others may have changes in receptor sensitivity or downstream signaling pathways.

The brain does not operate like a simple container that needs refilling. Neurotransmitters interact with each other in complex feedback loops. Changing one system can ripple across many others. This complexity explains why depression presents differently in different people and why no single treatment works for everyone.

Synapses, Receptors, and Signal Strength

The chemistry of depression is not only about which chemicals are present, but how neurons respond to them. Receptors on neurons act like molecular locks, responding only to specific chemical keys. In depression, these receptors can become less responsive or overly sensitive, altering how signals are processed.

Chronic stress, for example, can change receptor density in certain brain regions. Over time, neurons may reduce their responsiveness as a protective mechanism. What once felt rewarding may no longer register. Motivation fades not because desire disappears, but because the chemical signals that generate it are muted.

This synaptic plasticity, the brain’s ability to change its connections, is both a vulnerability and a source of hope. The same mechanisms that allow depression to take hold also allow recovery to occur when conditions change.

The Role of Dopamine and the Loss of Pleasure

One of the most painful aspects of depression is anhedonia, the reduced ability to feel pleasure. This experience is closely tied to dopamine signaling in the brain’s reward pathways. Dopamine does not simply create pleasure; it fuels anticipation, motivation, and the sense that effort is worthwhile.

In depression, dopamine pathways often become less active or less responsive. Activities that once felt meaningful lose their emotional impact. This is not laziness or indifference. It is a neurochemical state in which the brain’s reward system is underactive.

This loss of pleasure can create a cruel feedback loop. When effort brings no reward, motivation declines. When motivation declines, opportunities for positive experience decrease. Understanding the chemistry behind this cycle helps explain why depression can feel so immobilizing.

Stress Hormones and the Burden of Cortisol

Depression is closely linked to the body’s stress response system, particularly the hormone cortisol. Cortisol is essential for survival, helping the body respond to threats and challenges. In short bursts, it is adaptive. When stress becomes chronic, cortisol can become damaging.

Many people with depression show altered cortisol regulation. Levels may remain elevated or fail to follow normal daily rhythms. Excess cortisol can affect brain regions involved in mood and memory, particularly the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Over time, this can impair emotional regulation, concentration, and resilience.

The chemistry of stress and depression are deeply intertwined. Prolonged emotional stress can reshape brain chemistry, while altered brain chemistry can make stress harder to manage. Depression often reflects a system that has been pushed beyond its capacity to recover on its own.

Inflammation and the Immune-Brain Connection

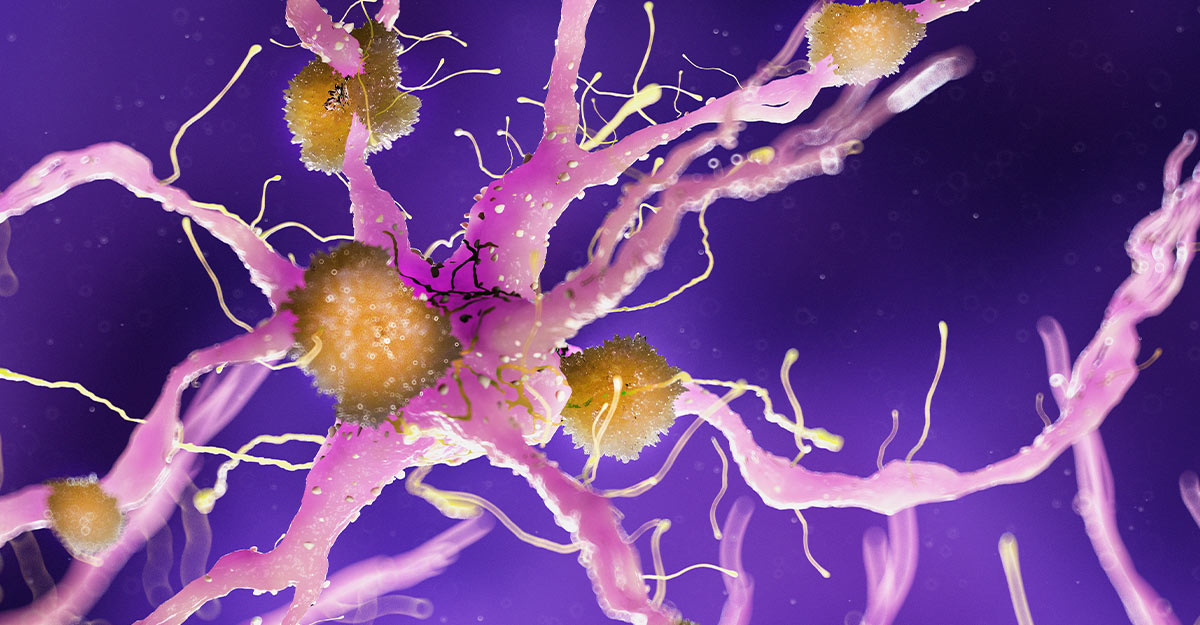

One of the most important developments in understanding depression is the recognition of the role of inflammation. The immune system and the brain are in constant communication through chemical signals called cytokines. When the immune system is activated, these molecules can influence brain function.

In some individuals, depression is associated with increased inflammatory markers. Inflammation can alter neurotransmitter metabolism, reduce dopamine availability, and interfere with neural plasticity. It can also produce symptoms that overlap with depression, such as fatigue, slowed thinking, and loss of interest.

This does not mean depression is simply an inflammatory disease, but it highlights how deeply interconnected bodily systems are. Emotional pain is not confined to the mind; it is reflected in the chemistry of the entire body.

Neuroplasticity and the Shrinking of Emotional Space

The brain is not fixed. It changes structurally and chemically in response to experience, a property known as neuroplasticity. Depression is associated with reduced plasticity in certain brain regions, meaning neurons become less adaptable and less able to form new connections.

This reduction in plasticity can make negative thought patterns more rigid and recovery more difficult. Emotional responses become stuck, replaying the same themes of hopelessness and self-criticism. Chemistry plays a central role here, influencing growth factors that support neuron health and connectivity.

The idea that depression involves a loss of neural flexibility reframes the condition. Depression is not simply feeling bad; it is the narrowing of emotional and cognitive possibilities. Recovery, then, involves reopening that space.

Genetics and Individual Vulnerability

Depression does not arise from chemistry alone, but genetics shape how brain chemistry responds to life. Certain genetic variations influence how neurotransmitters are produced, transported, and broken down. Others affect stress hormone regulation or inflammatory responses.

Genes do not determine destiny. They create tendencies, not certainties. A person may inherit a brain chemistry that is more sensitive to stress, but whether depression develops depends on environment, relationships, and experience. Chemistry sets the stage, but life writes the script.

Understanding genetic vulnerability helps explain why depression can appear without an obvious cause and why similar life events affect people differently. It reinforces the idea that depression is not a personal failure, but a complex interaction between biology and circumstance.

Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Chemical Timing

Sleep disturbances are both a symptom and a contributor to depression. The brain’s chemical systems follow daily rhythms regulated by internal biological clocks. Neurotransmitter release, hormone levels, and neural activity fluctuate over the day and night.

Depression often disrupts these rhythms. Sleep may become fragmented, excessive, or elusive. These disruptions further alter brain chemistry, affecting mood regulation and cognitive function. The relationship between sleep and depression is circular, each influencing the other.

This chemical timing matters deeply. Mood is not only about what chemicals are present, but when and how they are released. Depression often reflects a loss of synchrony within the brain’s chemical orchestra.

Early Experience and Chemical Imprints

The chemistry of depression is shaped early in life. Childhood stress, trauma, or neglect can alter the development of stress response systems and neurotransmitter pathways. These changes may persist into adulthood, creating a heightened vulnerability to depression later in life.

Early experiences can influence how genes are expressed through chemical markers that regulate DNA activity. These changes do not alter genetic code, but they affect how chemistry unfolds over time. The brain remembers early emotional environments not only psychologically, but chemically.

This understanding emphasizes compassion. Many people carry chemical imprints of experiences they did not choose. Depression, in this light, becomes a story of adaptation to difficult circumstances rather than personal weakness.

Medication and the Chemistry of Relief

Medications used to treat depression interact with brain chemistry in diverse ways. Some alter neurotransmitter availability, others influence receptor sensitivity or downstream signaling pathways. Their effects are gradual, reflecting the brain’s need to adapt to chemical changes.

Importantly, medication does not create artificial happiness. It alters conditions within the brain that may allow emotional regulation to function more effectively. For some people, this chemical support can be life-changing. For others, different approaches may be more helpful.

The variability in response highlights the complexity of depression’s chemistry. There is no universal chemical signature, and therefore no universal solution. Treatment is often a process of discovery rather than a single intervention.

Meaning, Emotion, and the Limits of Chemistry

While chemistry plays a central role in depression, it does not replace meaning. Neurotransmitters do not tell the whole story of loss, identity, or despair. Chemistry explains how emotional pain manifests in the brain, but it does not define the content of that pain.

Depression often involves themes of worth, connection, and purpose. These experiences are deeply human and cannot be reduced to molecules alone. Yet chemistry shapes how intensely these experiences are felt and how flexible the mind is in responding to them.

Understanding the chemistry of depression should deepen empathy, not diminish it. Knowing that despair has a biological basis does not make it less real; it makes it more deserving of care and understanding.

The Brain’s Capacity for Change and Hope

One of the most important truths about the chemistry of depression is that it is not static. The same brain systems that become dysregulated can also recover. Neuroplasticity allows chemical pathways to shift, receptors to adapt, and networks to reorganize.

Change often takes time. Chemistry responds gradually, reflecting the brain’s complexity. Recovery is rarely a sudden switch, but a slow rebalancing. This process can feel frustrating, but it reflects the brain’s careful adaptation rather than failure.

Hope in depression is not naive optimism. It is grounded in biology. The brain is capable of change, even after long periods of suffering. Chemistry does not lock a person into despair forever.

Depression as a Whole-Body Experience

The chemistry of depression extends beyond the brain. Appetite, energy, pain sensitivity, and immune function can all be affected. Depression is a systemic condition, influencing how the entire body feels and functions.

This whole-body impact explains why depression is exhausting, not just emotionally but physically. Fatigue, aches, and slowed movement are not imagined; they reflect real chemical changes throughout the body.

Recognizing depression as a whole-body experience helps counter the misconception that it is “all in the head.” It is in the head, but the head is part of the body, and the body is part of the lived experience of being human.

Stigma, Science, and Understanding

Scientific understanding of depression’s chemistry has played a crucial role in reducing stigma. When depression is seen as a biological condition shaped by life experience, blame loses its power. People are no longer told to simply “snap out of it” when the science shows how deeply rooted the condition can be.

At the same time, science must be communicated carefully. Oversimplified chemical explanations can unintentionally erase personal experience. True understanding holds both biology and meaning together, recognizing that depression is real, complex, and deeply human.

The chemistry of depression does not strip away individuality. It highlights how unique each brain is and how differently suffering can manifest.

Living with the Knowledge of Brain Chemistry

Knowing the chemistry behind depression can be both comforting and unsettling. Comforting, because it validates suffering as real and biological. Unsettling, because it reveals how vulnerable the mind is to invisible processes.

Yet this knowledge also empowers. Understanding that mood is influenced by chemistry can reduce self-blame and open pathways to support. It can encourage patience with oneself during recovery and compassion toward others who struggle.

Science does not replace empathy, but it can strengthen it by showing how deeply interconnected we all are at the level of biology.

Depression, Chemistry, and the Human Story

Depression is not a failure of happiness. It is a disruption of systems designed to help humans adapt, connect, and survive. Chemistry is the medium through which this disruption unfolds, but the experience of depression remains profoundly personal.

Every molecule involved in depression is part of a living story. Neurotransmitters carry not just signals, but the weight of experience. Hormones reflect not only stress, but the body’s attempt to cope. Inflammation speaks of a system responding to perceived threat.

To understand the chemistry of depression is to see suffering as meaningful, not mysterious or shameful. It is to recognize that emotional pain has roots in the same biological processes that allow love, joy, and resilience.

A Closing Reflection on Science and Compassion

The chemistry of depression teaches a humbling lesson. The mind is not separate from the body, and emotion is not separate from biology. We are chemical beings who feel deeply, think abstractly, and search for meaning in a universe governed by physical laws.

Depression reminds us that vulnerability is built into our design. The same chemistry that allows profound connection also allows profound pain. Understanding this does not make suffering disappear, but it can soften judgment and deepen care.

In the end, the chemistry of depression is not just a scientific topic. It is a story about how fragile and resilient the human brain can be, how deeply life shapes biology, and how science and compassion must move together if we are to truly understand what it means to suffer, to heal, and to be human.