Sleep is often treated as negotiable, a flexible buffer that can be trimmed to make room for work, study, entertainment, or worry. In a world that prizes productivity and constant connectivity, chronic sleep loss has quietly become one of the most widespread and underestimated threats to human health. Its consequences extend far beyond daytime fatigue or irritability. Over the past several decades, scientific research has revealed a deeply troubling connection between long-term sleep deprivation and neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia worldwide, slowly eroding memory, reasoning, identity, and independence. Once considered an inevitable consequence of aging or genetic destiny, Alzheimer’s is now understood as a complex biological process influenced by lifestyle, environment, and long-term physiological stress. Among these influences, sleep has emerged as a critical and powerful factor. The growing body of evidence suggests that chronic sleep loss does not merely accompany Alzheimer’s disease but may actively contribute to its development and progression.

This connection forces a profound rethinking of sleep itself. Sleep is not passive rest or mental shutdown. It is a biologically active, meticulously organized state essential for brain maintenance, memory consolidation, and metabolic cleanup. When sleep is repeatedly disrupted or shortened over years and decades, the brain may become vulnerable to the very processes that define Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding this connection is not only a scientific challenge but a deeply human one, touching nearly every family and community.

Alzheimer’s Disease: A Slow and Relentless Brain Disorder

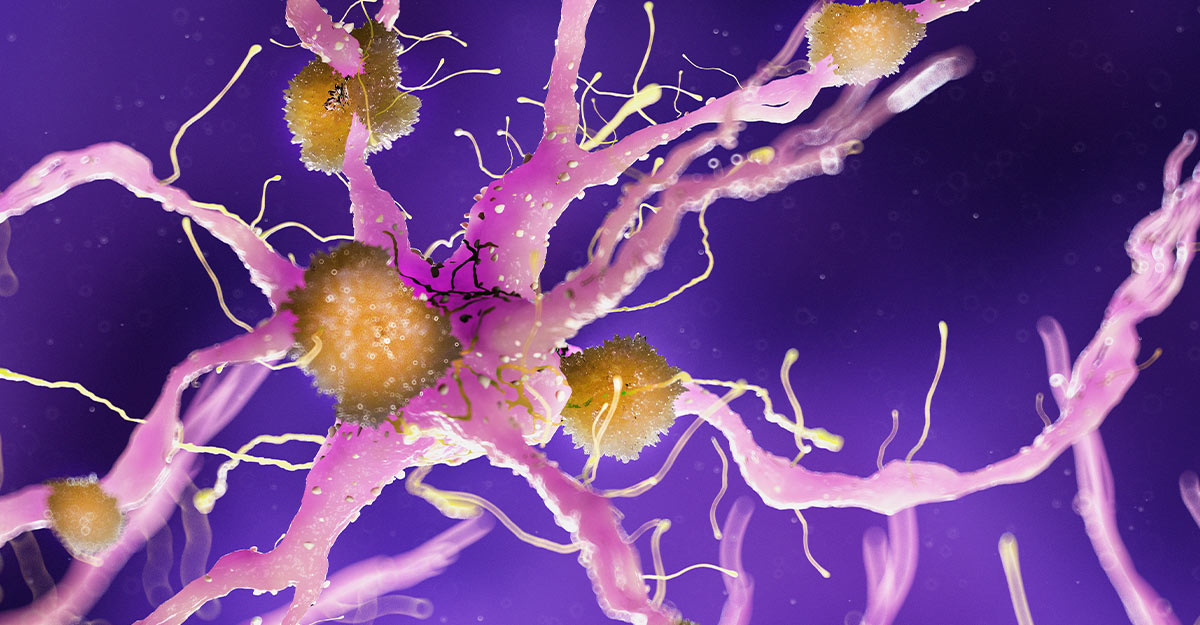

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by progressive cognitive decline, beginning subtly with memory lapses and gradually advancing to severe impairment of thinking, language, and behavior. At the biological level, the disease is defined by two hallmark abnormalities in the brain: the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques outside neurons and the formation of tau protein tangles inside neurons. Together, these pathological features disrupt communication between brain cells, impair synaptic function, and ultimately lead to widespread neuronal death.

Amyloid-beta is a protein fragment produced during normal brain activity. In a healthy brain, it is cleared efficiently. In Alzheimer’s disease, however, amyloid-beta accumulates and clumps together, forming sticky plaques that interfere with neural signaling. Tau, a protein that normally stabilizes internal cellular structures, becomes abnormally modified and aggregates into twisted filaments called neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles choke neurons from within, further accelerating cognitive decline.

For decades, researchers focused primarily on genetics and aging as the primary drivers of Alzheimer’s disease. While age remains the strongest risk factor and certain genetic variants significantly increase susceptibility, it has become increasingly clear that biology alone does not tell the full story. Lifestyle factors such as cardiovascular health, physical activity, cognitive engagement, and sleep patterns appear to shape the brain’s vulnerability to Alzheimer’s pathology long before symptoms appear.

The Architecture of Healthy Sleep

To understand how sleep loss might influence Alzheimer’s disease, it is essential to understand what healthy sleep actually does for the brain. Sleep is not a uniform state but a dynamic cycle consisting of distinct stages that repeat throughout the night. These stages include non-rapid eye movement sleep and rapid eye movement sleep, each playing specialized roles in brain function.

Deep non-rapid eye movement sleep, often called slow-wave sleep, is particularly important for brain restoration. During this phase, brain activity becomes synchronized and slow, energy consumption decreases, and certain restorative processes accelerate. Rapid eye movement sleep, on the other hand, is associated with vivid dreaming, emotional processing, and memory integration. Together, these stages support learning, emotional regulation, and cognitive resilience.

Sleep also regulates hormonal balance, immune function, and metabolic processes. Disruptions in sleep architecture, even without dramatic reductions in total sleep time, can impair these functions. Chronic sleep loss alters the balance of neurotransmitters, increases inflammatory signaling, and elevates stress hormones, all of which can negatively affect brain health over time.

The Brain’s Nightly Cleaning System

One of the most groundbreaking discoveries linking sleep to Alzheimer’s disease came from the identification of the brain’s glymphatic system. This system, described relatively recently, functions as a waste clearance pathway that becomes particularly active during sleep. Cerebrospinal fluid flows through brain tissue, washing away metabolic byproducts and potentially toxic proteins, including amyloid-beta.

During deep sleep, brain cells shrink slightly, creating more space between them. This expansion allows cerebrospinal fluid to circulate more efficiently, enhancing the removal of waste products that accumulate during waking hours. When sleep is shortened or fragmented, this cleaning process becomes less effective. As a result, amyloid-beta and other metabolites may begin to accumulate in the brain.

Experimental studies have shown that even a single night of sleep deprivation can increase amyloid-beta levels in certain brain regions. Over years of chronic sleep loss, this impaired clearance may contribute to the gradual buildup of amyloid plaques, setting the stage for Alzheimer’s pathology long before cognitive symptoms emerge.

Sleep Loss and Amyloid-Beta Accumulation

The relationship between sleep and amyloid-beta appears to be bidirectional and self-reinforcing. Poor sleep leads to increased amyloid-beta accumulation, and increased amyloid-beta, in turn, disrupts sleep. This vicious cycle may accelerate disease progression.

Amyloid-beta interferes with neural circuits involved in regulating sleep-wake rhythms, particularly in brain regions that generate slow-wave sleep. As amyloid accumulates, deep sleep becomes fragmented and less restorative. This reduction in deep sleep further impairs amyloid clearance, allowing even more accumulation to occur. Over time, this feedback loop may push the brain closer to the threshold of clinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Importantly, these changes can begin decades before memory loss becomes noticeable. Longitudinal studies suggest that individuals with chronically poor sleep in midlife are at higher risk of developing cognitive decline later in life. This temporal gap underscores the importance of sleep as a long-term investment in brain health rather than a short-term comfort.

Tau Pathology and Sleep Disruption

While amyloid-beta has received much attention, tau pathology is more closely correlated with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Emerging evidence indicates that sleep loss may also influence tau dynamics in the brain.

Experimental studies in animal models have shown that sleep deprivation increases extracellular tau levels, promoting its spread across brain regions. Tau appears to propagate along neural connections, and sleep loss may facilitate this propagation by altering neural activity patterns and synaptic stability. In humans, disrupted sleep has been associated with greater tau burden in brain imaging studies.

Unlike amyloid-beta, which tends to accumulate diffusely, tau pathology follows a more predictable pattern, beginning in memory-related regions and gradually spreading. Sleep disruption may accelerate this spread, hastening the transition from silent pathology to symptomatic disease.

Circadian Rhythms and Neurodegeneration

Sleep is governed not only by the need for rest but by circadian rhythms, the internal biological clocks that synchronize physiological processes with the day-night cycle. These rhythms regulate hormone release, body temperature, metabolism, and cognitive performance. Disruption of circadian rhythms, as seen in shift work, irregular sleep schedules, or chronic insomnia, has been linked to increased risk of neurodegenerative disease.

In Alzheimer’s disease, circadian rhythms become increasingly disorganized. Patients often experience sleep fragmentation, nighttime wandering, and daytime drowsiness. While these symptoms were once considered consequences of neurodegeneration, growing evidence suggests they may also contribute to disease progression by exacerbating sleep loss and metabolic stress.

Circadian disruption affects the timing of amyloid-beta production and clearance, further complicating the relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Maintaining regular sleep-wake cycles may therefore be as important as total sleep duration in protecting brain health.

Inflammation, Stress, and the Sleep-Deprived Brain

Chronic sleep loss triggers a cascade of physiological stress responses that can damage the brain over time. Sleep deprivation increases levels of inflammatory molecules and stress hormones, creating a neurochemical environment that may promote neurodegeneration.

Inflammation plays a central role in Alzheimer’s disease. Activated immune cells in the brain, known as microglia, can become chronically overactive in response to persistent stress and sleep disruption. While microglia are essential for clearing debris and maintaining neural health, excessive activation can lead to collateral damage, impairing synapses and releasing toxic substances.

Stress hormones such as cortisol also rise with chronic sleep deprivation. Elevated cortisol has been associated with hippocampal atrophy, a key feature of Alzheimer’s disease. Over time, the combined effects of inflammation and stress may weaken the brain’s resilience, making it more susceptible to pathological changes.

Memory Consolidation and Cognitive Reserve

Sleep plays a critical role in memory consolidation, the process by which newly acquired information is stabilized and integrated into long-term memory. During sleep, particularly deep and rapid eye movement sleep, neural circuits involved in learning are reactivated, strengthening connections and enhancing recall.

Chronic sleep loss impairs this process, leading to subtle cognitive deficits that may accumulate over time. Reduced memory consolidation can erode cognitive reserve, the brain’s ability to compensate for age-related changes and pathology. Individuals with greater cognitive reserve often show fewer symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease despite similar levels of brain pathology.

By undermining learning, attention, and memory, long-term sleep deprivation may reduce cognitive reserve and hasten the onset of clinical symptoms once Alzheimer’s pathology begins to accumulate.

Epidemiological Evidence Linking Sleep and Alzheimer’s Risk

Population-based studies provide compelling evidence that chronic sleep disturbances are associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Individuals who consistently report short sleep duration, poor sleep quality, or frequent insomnia symptoms are more likely to develop cognitive impairment later in life.

Long-term studies following participants over decades suggest that sleep patterns in midlife are particularly important. Poor sleep during these years may initiate or accelerate pathological processes that remain silent for many years before manifesting as dementia. Importantly, these associations persist even after accounting for other risk factors such as cardiovascular disease, depression, and physical inactivity.

While epidemiological studies cannot prove causation, their consistency across populations strengthens the argument that sleep loss is not merely a symptom of neurodegeneration but a contributing factor.

Sleep Disorders and Alzheimer’s Disease

Certain sleep disorders appear to carry particularly strong associations with Alzheimer’s disease. Obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by repeated breathing interruptions during sleep, leads to intermittent hypoxia and severe sleep fragmentation. These physiological stresses may exacerbate amyloid accumulation, inflammation, and vascular damage in the brain.

Insomnia, especially when chronic, is also linked to increased Alzheimer’s risk. Difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep reduces time spent in restorative sleep stages and disrupts circadian rhythms. Restless sleep may therefore have cumulative effects on brain health.

Understanding and treating sleep disorders may represent a critical opportunity for reducing Alzheimer’s risk, particularly in individuals already vulnerable due to age or genetic factors.

The Genetic Dimension and Sleep Vulnerability

Genetics influences both sleep patterns and Alzheimer’s susceptibility. Certain genetic variants associated with Alzheimer’s disease also appear to affect sleep regulation and circadian rhythms. This overlap suggests that some individuals may be biologically predisposed to both sleep disruption and neurodegeneration.

However, genetic risk is not destiny. Lifestyle factors, including sleep habits, can modify the expression of genetic vulnerabilities. Adequate sleep may help buffer genetic risk by supporting efficient waste clearance, reducing inflammation, and preserving cognitive reserve.

This interaction between genes and sleep underscores the importance of viewing Alzheimer’s disease through a multidimensional lens, where biology and behavior intersect over the lifespan.

Sleep as a Window for Prevention

The emerging connection between chronic sleep loss and Alzheimer’s disease offers a rare source of cautious optimism. Unlike many risk factors that are difficult or impossible to change, sleep is, at least in principle, modifiable. Improving sleep quality and duration may represent a practical and accessible strategy for supporting long-term brain health.

Interventions that promote consistent sleep schedules, reduce sleep fragmentation, and enhance deep sleep may help slow or prevent the accumulation of Alzheimer’s pathology. While sleep improvement alone is unlikely to eliminate risk entirely, it may significantly shift the trajectory of disease development.

Clinical trials are increasingly exploring whether sleep-based interventions can reduce biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease or delay cognitive decline. Although definitive answers remain forthcoming, the scientific rationale for prioritizing sleep has never been stronger.

Rethinking Sleep in Modern Society

The connection between sleep loss and Alzheimer’s disease forces a broader societal reckoning. Chronic sleep deprivation is not merely an individual choice but a cultural phenomenon shaped by work demands, technology, urban environments, and social expectations. Artificial light, constant connectivity, and irregular schedules erode natural sleep rhythms, often beginning early in life.

If sleep is essential for maintaining brain health across decades, then widespread sleep deprivation represents a collective risk with profound public health implications. Addressing this challenge requires not only individual awareness but structural changes that recognize sleep as a biological necessity rather than a luxury.

The Emotional Weight of the Connection

Alzheimer’s disease is not only a neurological disorder but an emotional and relational one. It alters memories that define personal identity and reshapes family bonds. The idea that something as ordinary and overlooked as sleep might influence this devastating disease carries both hope and urgency.

Sleep is woven into daily life, shared in routines, rituals, and quiet moments. Protecting sleep may be one of the most intimate ways we care for the future self, preserving not just cognitive function but the stories, relationships, and inner continuity that define a human life.

A Wake-Up Call for Brain Health

The scientific link between chronic sleep loss and Alzheimer’s disease is no longer speculative. It is grounded in molecular biology, brain imaging, animal studies, and long-term human data. Together, these lines of evidence tell a coherent and sobering story: the brain depends on sleep to protect itself from the very processes that drive neurodegeneration.

Sleep is not passive downtime. It is an active, essential process of repair, cleansing, and integration. When sleep is repeatedly sacrificed, the brain may pay a price that is not immediately visible but profoundly consequential over time.

Understanding this connection reframes sleep as a cornerstone of brain health, alongside nutrition, physical activity, and cognitive engagement. In the long struggle against Alzheimer’s disease, sleep may represent one of the most powerful, accessible, and underappreciated tools we have.