Every evening, the same quiet battle plays out in countless homes around the world. Parents urge their teenagers to go to bed. Teenagers insist they are not tired. Lights stay on, phones glow under blankets, homework stretches into the night, and sleep arrives far later than adults think is reasonable. In the morning, exhaustion reigns. Alarms are snoozed. School feels unbearable. To many adults, this pattern looks like stubbornness, laziness, or rebellion.

But beneath this nightly struggle lies a powerful truth: teenagers are not choosing late nights simply out of habit or defiance. Their brains are biologically wired for it.

Adolescence is not just a social or emotional transition. It is a profound neurological transformation. During these years, the brain undergoes dramatic changes that affect judgment, emotion, motivation, and, crucially, sleep. Understanding why teenagers stay up late requires stepping inside the adolescent brain and listening to the rhythms of biology rather than the ticking of the clock.

Sleep as a Biological Rhythm, Not a Moral Choice

Sleep is often framed as a matter of discipline. Go to bed earlier. Wake up earlier. Try harder. But sleep is not governed by willpower alone. It is controlled by intricate biological systems that operate beneath conscious control. These systems evolved to align the body with the natural cycle of day and night, regulating when we feel alert and when we feel sleepy.

At the center of this regulation is the circadian rhythm, an internal clock that runs on roughly a 24-hour cycle. This clock influences body temperature, hormone release, alertness, and sleep timing. In adults, the circadian rhythm tends to align relatively well with early mornings and earlier bedtimes. In teenagers, however, this clock shifts.

This shift is not a mistake or a malfunction. It is a normal and universal feature of human development.

The Adolescent Shift in the Internal Clock

As children enter puberty, their circadian rhythm undergoes a noticeable delay. This means their internal clock tells them to feel sleepy later at night and to wake up later in the morning. A teenager who feels wide awake at 11 p.m. is not ignoring sleep signals; those signals simply have not arrived yet.

This biological delay can be measured in hormone release. Melatonin, often called the sleep hormone, plays a key role in signaling the brain that it is time to sleep. In children, melatonin levels rise relatively early in the evening. In adolescents, the release of melatonin shifts later by one to two hours or more.

As a result, a bedtime that felt natural at age ten can feel impossibly early at age fifteen. The teenage brain is operating on a different schedule, one that clashes sharply with early school start times and adult expectations.

Puberty and the Rewiring of Sleep

Puberty is often discussed in terms of physical changes, but its neurological impact is just as profound. Hormonal changes during puberty influence not only growth and reproduction but also brain development. These hormones interact with the systems that regulate sleep and wakefulness.

The adolescent brain becomes more sensitive to evening light, particularly artificial light. Screens, indoor lighting, and even streetlights can delay melatonin release further, reinforcing the natural tendency toward later bedtimes. This sensitivity is not simply a result of modern technology; it reflects an underlying biological vulnerability that existed long before smartphones.

In evolutionary terms, this shift may have served a purpose. Adolescents in early human societies may have played a role in evening vigilance, staying alert later to protect the group. While modern life no longer requires this function, the biological pattern remains.

The Two Forces That Control Sleep

Sleep timing is shaped by the interaction of two major biological processes. One is the circadian rhythm, the internal clock that determines when sleep feels appropriate. The other is sleep pressure, the gradual buildup of the need for sleep the longer we stay awake.

In teenagers, both of these processes change. Not only does the circadian rhythm shift later, but sleep pressure also builds more slowly. This means teenagers can stay awake longer without feeling overwhelmingly tired, even though they still need as much sleep as younger children.

This combination is powerful. The brain tells the teenager it is not yet time to sleep, and the body does not feel sufficiently exhausted to override that signal. The result is a natural tendency to stay up late, even when tomorrow’s early wake-up looms.

How Much Sleep Teenagers Actually Need

Contrary to the belief that adolescents can function well on minimal sleep, their brains still require a substantial amount of rest. Most teenagers need roughly eight to ten hours of sleep per night to support healthy brain function, emotional regulation, learning, and physical growth.

What changes is not the amount of sleep needed, but the timing of that sleep. When teenagers are forced to wake up early for school, their delayed sleep onset means they accumulate chronic sleep deprivation. This deprivation is not immediately obvious as a single dramatic collapse. Instead, it manifests gradually as irritability, difficulty concentrating, low motivation, and emotional volatility.

Over time, chronic sleep loss can have serious consequences for mental health, academic performance, and overall well-being.

The Teenage Brain Under Construction

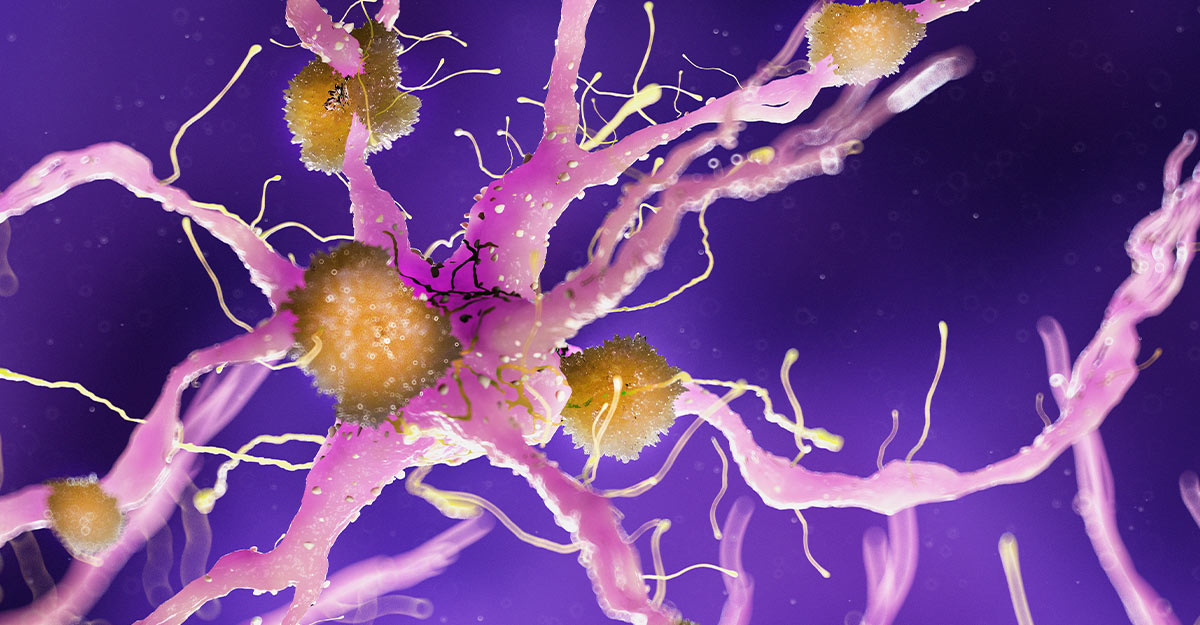

To understand why sleep is so critical during adolescence, it helps to recognize that the teenage brain is still under construction. During these years, the brain undergoes extensive remodeling. Neural connections that are frequently used are strengthened, while those that are unused are pruned away. This process makes the brain more efficient but also more vulnerable.

Sleep plays a vital role in this remodeling. During sleep, the brain consolidates memories, integrates learning, and clears metabolic waste. Disrupting sleep during this sensitive period can interfere with these processes, affecting learning and emotional development.

When teenagers are sleep-deprived, their brains struggle to perform the tasks demanded of them, not because they lack intelligence or effort, but because the neurological systems that support attention and self-control are impaired.

Emotional Intensity and Sleep Loss

Adolescence is often marked by heightened emotions, and sleep plays a key role in regulating emotional responses. The emotional centers of the brain develop earlier than the systems responsible for impulse control and rational decision-making. Sleep deprivation amplifies this imbalance.

When teenagers do not get enough sleep, their emotional reactions become more intense and less regulated. Minor frustrations feel overwhelming. Social conflicts escalate quickly. Anxiety and sadness become harder to manage. This emotional volatility is often misinterpreted as a character flaw, when in reality it is a predictable outcome of a sleep-deprived developing brain.

Adequate sleep acts as a stabilizer, helping teenagers navigate the emotional turbulence of adolescence with greater resilience.

Learning, Memory, and Late Nights

Teenagers are expected to absorb vast amounts of information during their school years. Sleep is essential for this learning process. During sleep, especially deep sleep and certain stages of dreaming, the brain replays and strengthens newly learned information.

Late nights followed by early mornings disrupt this process. Even when teenagers spend long hours studying, insufficient sleep can undermine their ability to retain and apply what they have learned. The brain may struggle to focus during classes, making learning feel frustrating and ineffective.

This creates a vicious cycle. Falling behind academically increases stress, which can further delay sleep, deepening sleep deprivation and its consequences.

Social Lives and the Nighttime Brain

Adolescence is a time when social connections become intensely important. Teenagers are biologically primed to seek peer interaction and social validation. Evening hours often provide the only time when social demands and academic pressures collide.

Late nights become a space for connection, identity exploration, and emotional expression. The teenage brain, already alert later at night, finds this time especially stimulating. Conversations deepen. Creativity flows. Emotions feel vivid and meaningful.

While social engagement is healthy, it can conflict with biological sleep needs when paired with early obligations. The issue is not that teenagers value sleep less, but that their brains assign high emotional reward to nighttime wakefulness.

The Clash Between Biology and Society

Modern society is structured around early schedules that favor adult circadian rhythms. Schools often start early in the morning, requiring teenagers to wake up at times that contradict their biological clocks. This mismatch creates a chronic state of jet lag, sometimes called social jet lag, where internal time and external demands are misaligned.

Unlike travel-related jet lag, this state does not resolve after a few days. It persists throughout the school year, accumulating sleep debt that teenagers can rarely repay, even on weekends.

This clash is not the teenager’s fault. It is a structural problem that arises when biological development is ignored in favor of tradition and convenience.

Weekends and the Illusion of Catch-Up Sleep

On weekends, many teenagers sleep late into the morning or early afternoon. This behavior is often criticized as laziness, but it reflects an attempt by the brain to recover lost sleep. The body seizes the opportunity to align sleep with its natural rhythm when external constraints are relaxed.

However, this catch-up sleep can further disrupt the circadian rhythm, making it even harder to fall asleep early on Sunday night. The result is a cycle of exhaustion that repeats each week.

Understanding this pattern requires compassion rather than judgment. The teenage brain is responding adaptively to chronic sleep deprivation, even if the outcome appears counterproductive.

Light, Screens, and the Modern Night

Artificial light has transformed human sleep patterns, and teenagers are especially sensitive to its effects. Exposure to bright light in the evening suppresses melatonin production, delaying sleep onset. Screens emit light that is particularly effective at triggering this response.

For teenagers whose melatonin release is already delayed, evening screen use can push sleep even later. This does not mean technology alone causes late nights, but it magnifies an existing biological tendency.

Blaming technology without acknowledging biology oversimplifies the problem. The issue lies in the interaction between a developing brain and an environment that offers constant stimulation long after sunset.

Risk-Taking and Sleep Deprivation

Adolescence is associated with increased risk-taking, a trait linked to ongoing brain development. Sleep deprivation intensifies this tendency. When tired, the brain’s ability to assess consequences and regulate impulses diminishes.

Late nights and insufficient sleep can therefore contribute to poor decision-making, increased vulnerability to stress, and difficulty managing complex situations. This does not imply that sleep loss causes all adolescent challenges, but it adds strain to an already demanding developmental stage.

Ensuring adequate sleep is one of the most effective ways to support healthier choices and emotional balance during adolescence.

Mental Health and the Nighttime Brain

The relationship between sleep and mental health is especially important during adolescence. Sleep disturbances are both a risk factor for and a symptom of conditions such as depression and anxiety. Chronic sleep deprivation can exacerbate emotional distress, while emotional distress can further disrupt sleep.

Teenagers who consistently struggle with sleep may experience feelings of hopelessness, irritability, and emotional numbness. Recognizing the biological roots of late nights can help reduce stigma and encourage supportive interventions rather than punishment.

Sleep is not a luxury for mental health; it is a foundational requirement.

The Misunderstood Teenager

When teenagers stay up late, adults often interpret the behavior through a moral lens. They see irresponsibility where there is biology, defiance where there is development. This misunderstanding can strain relationships and deepen conflict.

Recognizing that late nights are driven by neurological changes allows for a more compassionate approach. It shifts the conversation from blame to understanding, from control to collaboration.

Teenagers are not broken. Their brains are adapting to a critical phase of life, preparing them for independence, creativity, and complex social worlds.

Toward a More Biologically Aligned World

Understanding the biological basis of teenage sleep patterns invites broader reflection on how society structures time. When institutions align with human biology, people thrive. When they ignore it, stress and dysfunction follow.

Adjusting expectations around teenage sleep is not about indulgence. It is about respecting science and supporting healthy development. Even small shifts in awareness can reduce conflict and improve well-being.

Adolescence is temporary, but its impact is lasting. Supporting teenagers through this stage with empathy and evidence-based understanding can shape healthier adults and stronger communities.

The Beauty of the Adolescent Brain

The same neurological changes that push teenagers toward late nights also fuel creativity, passion, and emotional depth. The adolescent brain is not merely inconvenient; it is powerful. It questions norms, explores possibilities, and imagines new futures.

Late nights, in this sense, are not only a challenge but a reflection of a mind alive with energy and curiosity. When guided rather than suppressed, this energy can become a source of innovation and resilience.

Understanding why teenagers are wired for late nights allows us to see them not as problems to be fixed, but as humans in the midst of extraordinary transformation.

Listening to Biology, Listening to Youth

Science offers a clear message: teenage late nights are not a failure of discipline, but a feature of development. Biology speaks through hormones, neural circuits, and rhythms shaped by evolution.

Listening to this message requires humility and change. It asks adults to reconsider assumptions and to meet teenagers where they are, not where convenience dictates they should be.

When we listen to biology, we also listen to youth. And in doing so, we create space for healthier sleep, stronger relationships, and a deeper respect for the remarkable journey of growing up.