The first time you forgot a phone number you once knew by heart, it may not have felt important. The second time you reached for your phone to remember an address, a birthday, or even what you had planned to do next, it probably felt normal. After all, technology is supposed to help us. Yet somewhere between convenience and dependence, a quiet question has emerged: what happens to the human mind when it no longer needs to remember?

The term “digital dementia” captures a growing unease in the modern world. It suggests that constant interaction with digital devices may be weakening our short-term memory and cognitive abilities, not through disease, but through disuse. The phrase itself is emotionally charged, evoking fear, loss, and the idea that something precious is slipping away. But beneath the alarm lies a deeper, more nuanced story about how memory works, how technology reshapes mental habits, and what it means to think in the digital age.

This is not a story of simple decline or technological villainy. It is a story of adaptation, trade-offs, and the fragile balance between external tools and internal mental strength. To understand whether technology is eroding our short-term memory, we must first understand what memory is, how it evolved, and why it matters so deeply to our sense of self.

The Nature of Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is the mind’s workspace. It is the mental space where information is briefly held, manipulated, and either discarded or stored for later use. When you hear a sentence and understand it, when you calculate numbers in your head, when you follow directions or remember why you walked into a room, you are using short-term memory.

Scientifically, short-term memory is closely linked to working memory, a system that allows us to hold information temporarily while performing tasks. It has limited capacity and duration. This limitation is not a flaw but a feature. It forces the brain to prioritize, focus, and process information efficiently. Short-term memory is deeply connected to attention, concentration, and executive control, making it central to learning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

From an evolutionary perspective, short-term memory helped humans survive. It allowed early humans to track threats, remember recent events, and coordinate actions in dynamic environments. Over time, it became intertwined with language, reasoning, and creativity. Short-term memory is not just about holding facts; it is about making sense of the present moment.

Memory as a Muscle of the Mind

Memory, like muscle, grows stronger with use and weaker with neglect. When we repeatedly engage our short-term memory, we reinforce neural pathways that support attention and recall. When we rely on external tools instead, those pathways may be used less frequently.

This does not mean the brain is passive or fragile. The human brain is remarkably plastic, constantly reshaping itself in response to experience. If a skill is no longer needed, the brain reallocates resources elsewhere. This adaptability has allowed humans to thrive in changing environments. But it also means that cognitive habits matter.

The question at the heart of digital dementia is not whether technology damages the brain directly, but whether it changes how often and how deeply we use certain mental abilities. When devices remember for us, navigate for us, and remind us constantly, the brain may adapt by remembering less itself.

The Rise of External Memory

Human beings have always used external memory aids. Cave paintings, written language, books, calendars, and notebooks all serve as extensions of memory. Each technological leap sparked anxiety. Writing was once feared as a threat to memory, with critics arguing that people would stop remembering if knowledge could be written down.

Yet writing did not destroy memory. It transformed it. Humans shifted from memorizing vast amounts of information to focusing on understanding, interpretation, and creativity. External memory allowed civilization to grow.

Digital technology, however, represents a different scale and speed of externalization. Smartphones are not passive storage tools; they are interactive, omnipresent, and constantly demanding attention. They do not merely hold information; they anticipate needs, prompt actions, and shape behavior. This difference matters.

The Cognitive Cost of Convenience

Modern technology excels at reducing cognitive effort. GPS eliminates the need to remember routes. Search engines remove the need to recall facts. Notifications remind us of tasks before we even realize we might forget them. These tools are undeniably useful, but they change how memory is exercised.

Studies in cognitive science suggest that when people know information is easily accessible, they are less likely to store it in memory. Instead, they remember how to find the information. This phenomenon does not indicate stupidity or laziness; it reflects efficient adaptation. The brain prioritizes what seems useful.

Yet this efficiency comes with a cost. If short-term memory is consistently bypassed, the skills associated with it may weaken. Concentration may fragment. Mental endurance may decline. The ability to hold complex ideas in mind without external support may erode.

Attention, Distraction, and Memory

Short-term memory cannot function without attention. Attention acts as the gatekeeper, determining what enters memory and what fades away. In the digital age, attention is under constant assault.

Smartphones, social media platforms, and apps are designed to capture and hold attention. Notifications interrupt thought processes, fragmenting focus. Each interruption forces the brain to reset its mental workspace, increasing cognitive load and reducing memory retention.

When attention is continuously divided, short-term memory struggles. Information passes through consciousness without being encoded. This creates the subjective feeling of forgetfulness, even when memory capacity itself remains intact.

Over time, constant distraction may train the brain to expect interruption. Deep focus becomes uncomfortable. Sustained mental effort feels exhausting. This shift does not mean the brain is damaged, but it does mean it is being trained for a different cognitive environment.

The Emotional Experience of Forgetting

Forgetfulness carries emotional weight. Forgetting names, appointments, or intentions can provoke anxiety, shame, and fear. Many people worry that these lapses signal cognitive decline. The term digital dementia amplifies these fears, framing everyday forgetfulness as something pathological.

Emotion plays a crucial role in memory. Stress, anxiety, and fatigue impair short-term memory performance. Ironically, worrying about memory loss can make memory worse. In a world that demands constant responsiveness, mental overload becomes common, and memory suffers as a result.

The emotional environment created by digital life may be as important as the technology itself. Constant comparison, information overload, and pressure to stay connected create chronic stress. This stress undermines attention and memory, making forgetfulness more likely.

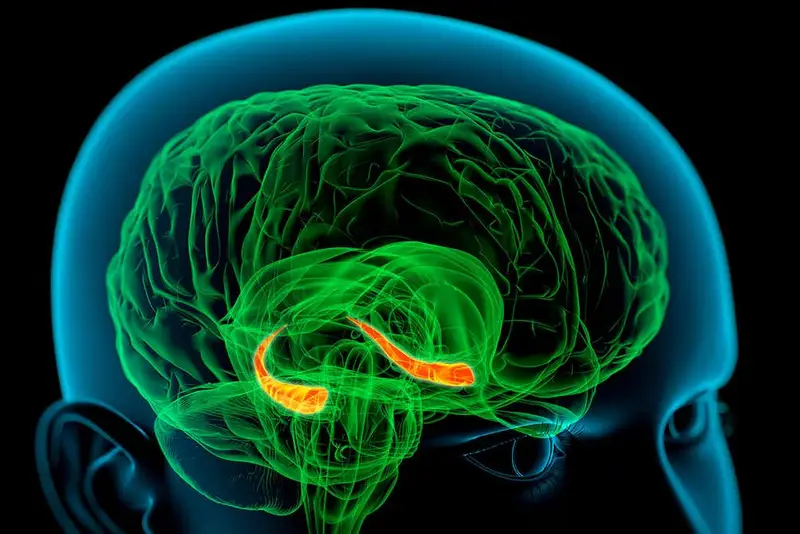

What Neuroscience Really Says

Despite popular alarm, neuroscience does not support the idea that technology causes dementia in the medical sense. Dementia involves progressive neurological damage, whereas digital-related cognitive changes are functional and reversible.

Brain imaging studies show that heavy technology use can change patterns of neural activity, particularly in attention and memory networks. However, change does not equal harm. The brain adapts to demands placed upon it.

The concern is not that neurons are dying, but that certain cognitive skills may be underused. Short-term memory capacity itself does not disappear, but the ability to deploy it effectively may weaken if not practiced.

Importantly, when people intentionally engage memory and attention, performance improves. This suggests that digital-related memory issues reflect habit rather than permanent loss.

Children, Adolescents, and Developing Minds

Concerns about digital dementia intensify when children are involved. Developing brains are highly plastic and sensitive to environmental input. Childhood is a critical period for building attention, memory, and self-regulation.

Research indicates that excessive screen time, particularly when it replaces active play, reading, and social interaction, can affect attention and memory development. Rapid, highly stimulating digital content may condition young minds to seek constant novelty, making sustained focus more difficult.

However, technology itself is not inherently harmful. Educational digital tools can enhance learning when used thoughtfully. The key factor is balance and context. Passive consumption differs from active engagement. Guided use differs from unrestricted exposure.

The fear that an entire generation is losing its memory oversimplifies a complex reality. Children adapt to their environments, and the challenge lies in shaping those environments wisely.

Adults, Multitasking, and Mental Fatigue

For adults, digital dementia often manifests as mental exhaustion rather than true memory loss. Multitasking, encouraged by digital devices, places heavy demands on working memory. Switching between tasks taxes cognitive resources and reduces efficiency.

Contrary to popular belief, humans are not good at multitasking. Each switch incurs a mental cost, increasing errors and reducing retention. Over time, this constant cognitive juggling can feel like declining memory.

Mental fatigue further compounds the problem. The brain has finite energy. Continuous stimulation without rest leads to diminished performance. Forgetfulness becomes a symptom of overload, not decay.

The Illusion of Infinite Knowledge

One of the most subtle effects of digital technology is the illusion of knowing. When information is always accessible, familiarity can masquerade as understanding. People may feel informed without deeply engaging with material.

Short-term memory plays a crucial role in building long-term knowledge. It allows information to be processed, connected, and integrated. When reliance on external sources replaces internal processing, learning becomes shallow.

This does not mean that technology prevents learning, but that learning requires intentional effort. Passive scrolling rarely challenges memory or comprehension. Deep learning demands focus, reflection, and mental struggle.

Memory, Identity, and Meaning

Memory is more than a cognitive function; it is central to identity. Our memories shape who we are, how we understand our past, and how we imagine our future. Short-term memory supports this process by enabling continuity of thought and experience.

When people feel mentally scattered, they often report a sense of disconnection from themselves. Thoughts feel fragmented. Time feels compressed. Life feels rushed. These experiences are not signs of brain damage but reflections of a fast-paced, attention-fragmented environment.

The fear surrounding digital dementia may stem less from actual memory loss and more from a loss of mental presence. Being constantly distracted can make life feel less coherent and less meaningful.

Technology as a Cognitive Partner

It is tempting to frame technology as an enemy of memory, but this view misses a crucial point. Technology is a tool, and tools reshape how humans think. Calculators changed arithmetic skills. Writing changed oral memory traditions. Maps changed navigation skills.

Rather than eroding intelligence, these tools freed cognitive resources for other tasks. The same may be true for digital memory aids. Offloading routine information can allow the brain to focus on creativity, problem-solving, and emotional intelligence.

The danger arises when tools replace thinking rather than support it. When technology dictates attention instead of serving intention, cognitive balance is lost.

Reclaiming Short-Term Memory in a Digital World

The good news is that short-term memory is resilient. It can be strengthened through practice, rest, and intentional habits. Engaging deeply with tasks, reducing unnecessary distractions, and allowing time for reflection all support memory.

Sleep plays a critical role in memory consolidation. Chronic sleep deprivation, common in digitally connected societies, impairs short-term memory and attention. Physical exercise also enhances cognitive function by improving blood flow and neural health.

Mindfulness and focused attention practices train the brain to sustain awareness. Reading long-form text, engaging in meaningful conversation, and solving complex problems all exercise working memory.

None of these require abandoning technology. They require conscious use.

The Ethical Responsibility of Design

Technology does not exist in a vacuum. Design choices influence behavior. Platforms optimized for engagement often exploit attentional vulnerabilities, prioritizing time spent over mental well-being.

There is growing recognition of ethical responsibility in technology design. Tools can be built to support focus rather than fragmentation, to encourage depth rather than distraction.

Society faces a choice. Technology can be shaped to respect cognitive limits and human values, or it can continue to compete aggressively for attention. The outcome will influence not just memory, but the quality of human experience.

Digital Dementia as a Cultural Mirror

The fear of digital dementia reflects broader anxieties about modern life. Rapid change, information overload, and constant connectivity challenge traditional rhythms of thought and rest. Memory becomes a symbol of control, stability, and selfhood.

Rather than asking whether technology is destroying memory, a more productive question is how culture values attention and mental health. Memory thrives in environments that allow focus, reflection, and emotional safety.

Digital dementia, then, may be less a medical condition and more a cultural warning. It invites reflection on how humans want to think, live, and remember in an increasingly digital world.

A Future of Coexistence, Not Decline

The human brain has survived countless transformations. It adapted to language, writing, printing, and electricity. There is no reason to believe it cannot adapt to digital technology.

The challenge lies in intentional coexistence. Memory does not disappear when supported by technology, but it does require care. Short-term memory thrives when attention is protected, when mental effort is valued, and when rest is respected.

Technology is not eroding memory by force. It is reshaping the cognitive landscape. Whether that landscape becomes barren or enriched depends on how humanity chooses to engage.

Remembering What Truly Matters

In the end, the question of digital dementia is not just about memory capacity. It is about presence. It is about whether humans remain mentally engaged with their own lives or drift through them guided by notifications and reminders.

Short-term memory allows us to hold the present moment long enough to understand it. When we lose that ability, not biologically but behaviorally, life feels thinner.

Technology can help us remember more than ever before, but it cannot decide what is worth remembering. That responsibility remains deeply human.