At first glance, the idea feels almost magical. Take particles with no charge, no chemical attraction, no instructions to stick together in any special way. Give them nothing but a shape and one simple rule: they cannot overlap. Then watch, as order quietly rises out of apparent nothingness.

This is the strange and elegant world explored by Rodolfo Subert and Marjolein Dijkstra of Utrecht University, whose recent study published in Nature Communications reveals how complex three-dimensional structures can emerge from particle shape alone. No electric forces. No chemical bonds. Just geometry, crowding, and the subtle push of entropy guiding matter toward what is most likely.

What unfolds in their simulations reads less like a technical exercise and more like a story about how nature finds patterns even when no one asks it to.

A Crowd of Silent Shapes

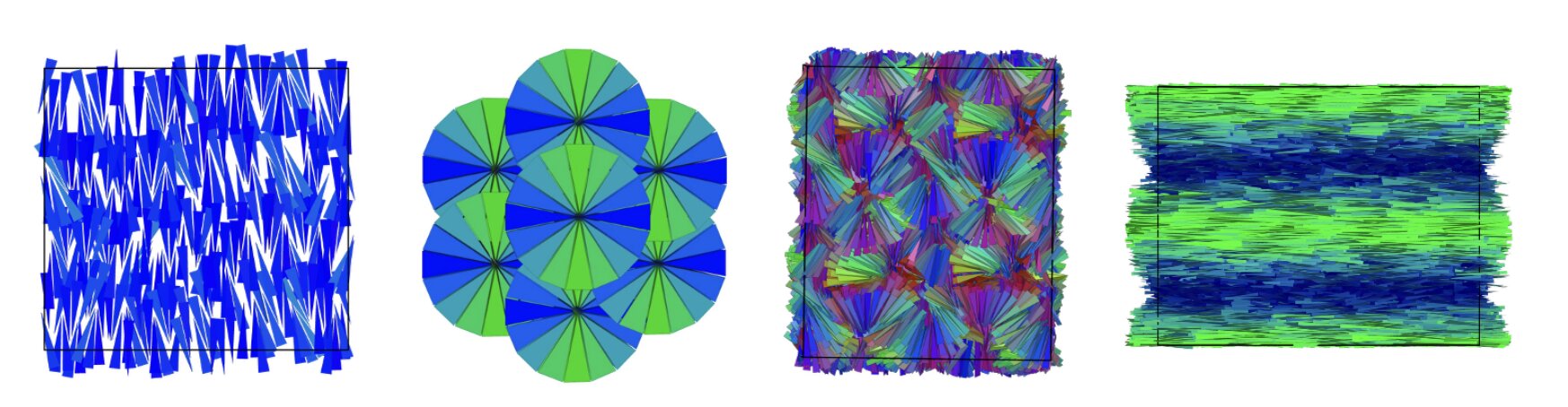

The researchers did not begin with real materials, but with carefully designed computer simulations. Inside these digital worlds lived particles shaped like hard polyhedra, solid geometric forms with flat faces and sharp edges. These particles followed a single law: they were forbidden from overlapping. There were no attractions pulling them together and no repulsions pushing them apart, beyond the simple fact that two objects cannot occupy the same space.

At low density, nothing remarkable happened. The particles floated around in disorder, like people scattered across an empty field. But as the virtual space became more crowded, something unexpected began to occur.

The particles started to organize.

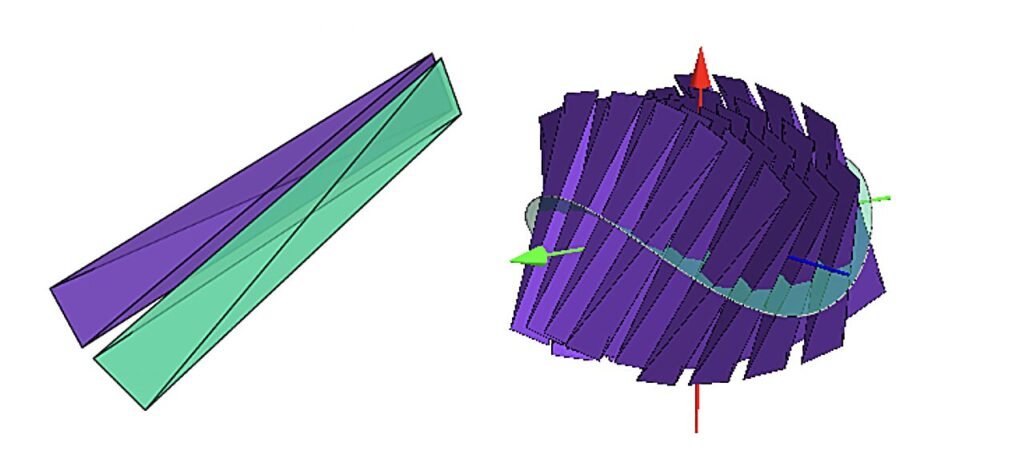

Without being told how, they aligned themselves into layers. As density increased further, those layers transformed into columns. Push the system even more, and the columns connected into intricate three-dimensional networks. Each step brought more structure, more order, emerging naturally from the simple constraints of shape and space.

The surprise was not just that order appeared, but that it appeared so reliably.

Entropy, the Quiet Architect

To understand why this happens, one must look beyond the idea that entropy always favors chaos. In everyday language, entropy is often described as disorder, but in physics it is better understood as probability. Systems tend to settle into states that can be realized in the largest number of ways.

In the crowded world of these simulations, complete randomness was no longer the most probable arrangement. Certain ordered structures allowed the particles more freedom to wiggle, rotate, and adjust without violating the no-overlap rule. Paradoxically, order became the easiest path.

The layers and networks were not imposed from the outside. They were simply the most likely solutions to a geometric puzzle played by thousands of particles at once.

This idea challenges a long-standing assumption in materials science: that complexity in structure requires complexity in interaction. Subert and Dijkstra show that sometimes, geometry alone can do the heavy lifting.

The Moment the Material Began to Twist

Then came the moment that truly caught the researchers off guard.

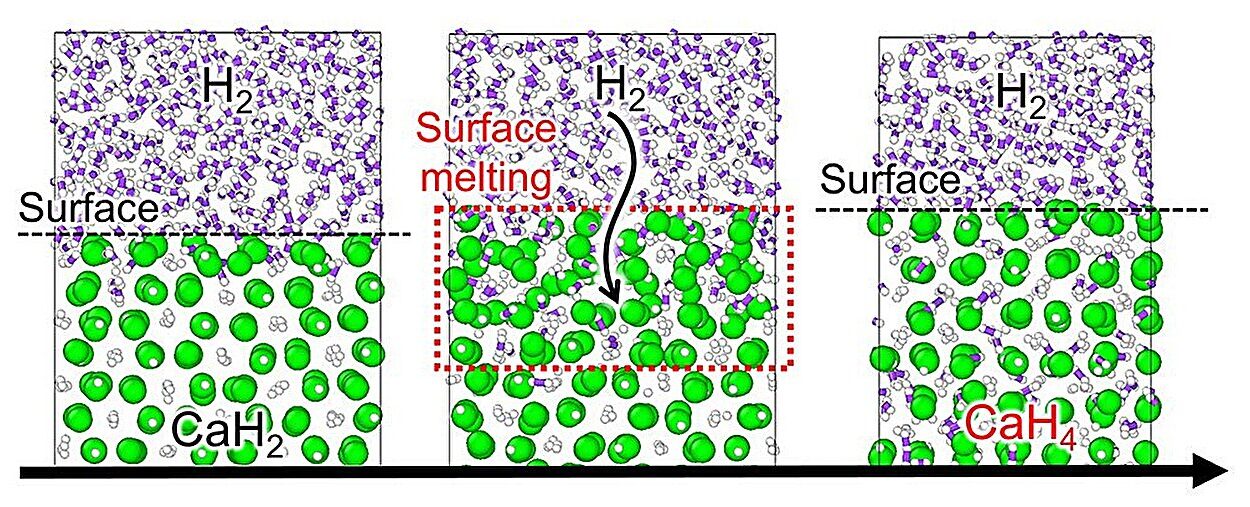

As the simulations continued, some of the structures began to twist. Not randomly, but with a clear preference. Entire assemblies leaned consistently to the left or to the right, forming patterns with a distinct handedness.

This phenomenon is known as chirality, a property familiar from biology and liquid crystals, where left-handed and right-handed forms behave differently. Until now, chirality was thought to arise mainly from complex, asymmetric molecules that carry a built-in twist.

But here, the particles themselves were not twisted at all.

“The particles themselves are not twisted,” says Marjolein Dijkstra, “but together they form a pattern with a preference for left or right twist. That direction is not built in anywhere.”

The twist emerged spontaneously, chosen by the collective behavior of many simple shapes acting together.

When Local Choices No Longer Agree

The key to this twisting lies in how particles prefer to sit next to one another. Because of their geometry, each particle has a slight preference for certain alignments with its neighbors. At small scales, these preferences work just fine. But as the structure grows, problems arise.

The local alignments cannot all be satisfied at once across the entire material. The system becomes frustrated, effectively jammed by its own geometry. Something has to give.

To relieve this tension, the structure bends, deforms, or twists. In doing so, it finds a new compromise that works on larger scales, even if no single particle gets its ideal arrangement. From this resolution of geometric conflict, complex global patterns emerge.

What looks like sophistication is really negotiation.

Simple Shapes, Predictable Outcomes

One of the most striking outcomes of the study is that different shapes tend to lead to different kinds of structures. Without invoking chemistry or external forces, the geometry itself acts as a design language.

Elongated shapes tend to produce twisted structures. Flatter shapes favor column-like arrangements. Shapes that fall between these extremes often give rise to network-like materials.

These are not rigid rules, but guiding principles that help explain why certain patterns appear again and again. According to Rodolfo Subert, understanding these simple relationships is essential for building a broader theory of material behavior.

“In our research, we show that sometimes surprisingly simple principles underlie complex patterns,” he explains.

From Virtual Worlds to Real Materials

Although the work exists entirely within simulations, it is not confined to theory. The particle shapes used in the study can, in principle, be manufactured using existing techniques in colloid science. This opens the door to experimental systems that test these ideas in the physical world.

If geometry alone can guide self-assembly, then materials might be designed not by tuning chemical interactions, but by carefully sculpting the shape of their building blocks. This approach could lead to materials with unusual optical properties, novel mechanical behavior, or structures that respond intelligently to their environment.

Instead of forcing matter into order, researchers could let it discover order on its own.

Why This Research Matters

At its heart, this study reshapes how we think about complexity in the material world. It suggests that intricate structures do not always require intricate causes. Sometimes, the quiet logic of shape and probability is enough.

By showing that chirality, networks, and layered organization can emerge from nothing more than particle geometry and entropy, Subert and Dijkstra expand the toolkit of materials science. They offer a simpler, more intuitive path toward understanding how matter organizes itself.

This matters not only for designing new technologies, but for deepening our understanding of nature itself. From biological systems to synthetic materials, the same lesson echoes: complexity can arise from simplicity, if the conditions are right.

In a universe governed by basic rules, even the most elaborate patterns may begin with something as humble as a shape.

Study Details

Rodolfo Subert et al, Hierarchical self-assembly of simple hard polyhedra into complex mesophases, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65891-w