For as long as many of us can remember, exercise has carried a powerful promise. Move more, sweat harder, burn calories, and the numbers on the scale should follow. It feels logical, almost comforting in its simplicity. Every step, every run, every workout is supposed to stack neatly on top of the energy our bodies already use just to exist. More movement, more burn, less weight.

But lived experience often tells a more confusing story. People train consistently, sometimes intensely, yet see little change in their waistlines. Frustration creeps in. Doubt follows. And a quiet question begins to form: if exercise is so good at burning calories, why doesn’t it always lead to weight loss?

A new study published in Current Biology steps directly into that uncomfortable gap between expectation and reality. Instead of blaming willpower or effort, it points to something deeper and far more fascinating. The answer may lie in how our bodies quietly rewrite the rules of energy use when we start moving more.

The Simple Equation That Shaped Our Thinking

For decades, scientists relied on a straightforward idea known as the Additive Model. It treats the body like a clean, honest calculator. According to this model, the total energy you burn in a day is simply the cost of staying alive plus whatever energy you spend exercising.

If your body uses 2,000 calories a day to keep your heart beating, your lungs breathing, and your brain thinking, and you go for a run that burns 400 calories, the math seems clear. Your daily total becomes 2,400 calories. That extra burn is supposed to tip the balance toward weight loss.

This equation shaped not only scientific thinking but also public health advice and personal fitness goals. It framed exercise as a reliable lever: pull it harder, and the energy output rises accordingly. Yet the human body, as it turns out, may not be so eager to follow tidy arithmetic.

A Different Way of Seeing the Body

In recent years, another idea has been quietly gaining ground. It is called the Constrained Model, and it paints a very different picture of how energy works.

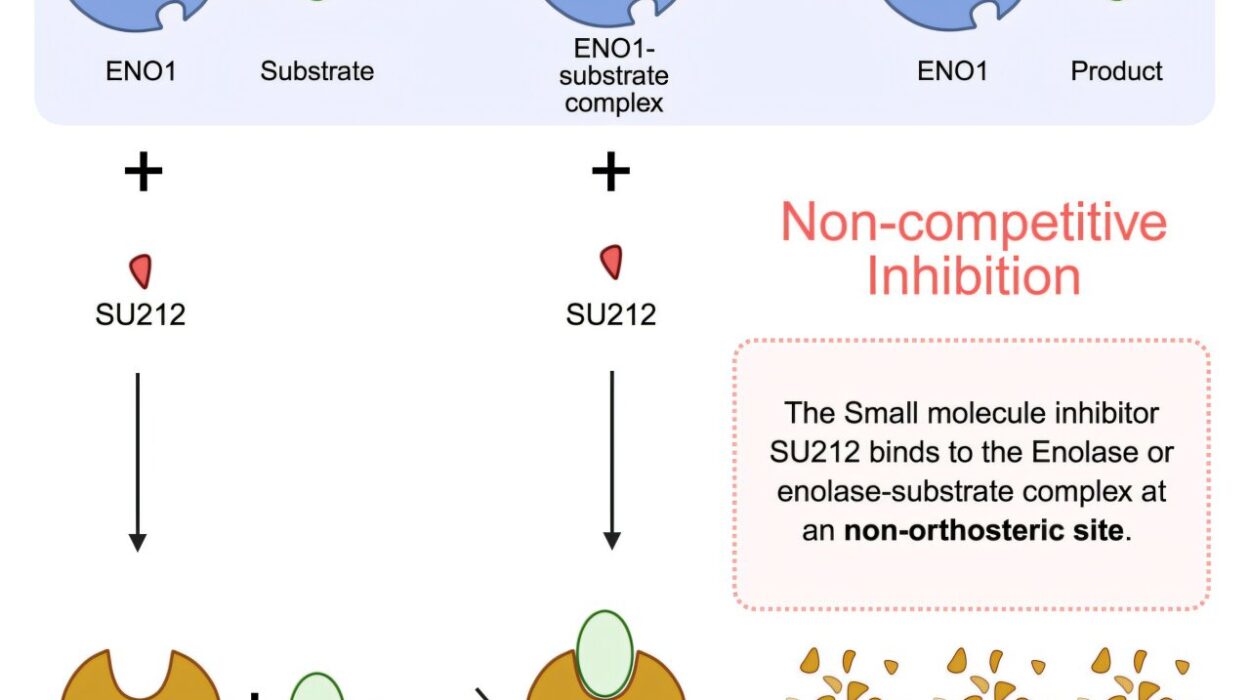

Instead of treating the body as endlessly additive, this model suggests that our energy expenditure has limits. When physical activity increases, the body doesn’t simply pile new calories on top of the old ones. Instead, it adjusts. Energy spent on exercise may be partially balanced by energy taken away from other internal tasks.

These tasks are not obvious. They happen beneath awareness, in the invisible maintenance work that keeps cells functioning and systems running smoothly. According to this model, when exercise demands more fuel, the body may quietly scale back elsewhere to keep total energy use within a narrow and predictable range.

This idea challenges something deeply ingrained. It suggests that the calories burned during a workout are not always the bonus we think they are.

Putting Two Beliefs Head to Head

To see which model better matched reality, two researchers from Duke University, Herman Pontzer and Eric T. Trexler, decided to let the data speak.

They didn’t rely on a single experiment or a narrow sample. Instead, they analyzed 14 different studies involving 450 people who took part in structured exercise programs. They also examined data from several animal studies, allowing them to compare patterns across species.

Their approach was careful and revealing. They looked at how much energy participants were expected to burn based on their activity and compared it with how much energy they actually burned in total. The gap between expectation and reality told a story of compensation. They also compared energy use across different populations, searching for consistent patterns.

What emerged was not a dramatic overthrow of old ideas, but a quiet correction. The Additive Model, they found, often overestimated how much total daily energy expenditure increases when activity rises.

The Body’s Subtle Balancing Act

The findings revealed something both surprising and deeply human. When people and animals become more physically active, their bodies tend to compensate by reducing energy spent on other processes or activities.

On average, about 72% of the calories burned during exercise are truly added to the total daily energy burn. The remaining 28% does not disappear, but it is offset. That energy is saved elsewhere, pulled back from tasks that are less immediately visible than a pounding heart or aching muscles.

This compensation is not absolute. Exercise still raises total energy expenditure. But the increase is smaller than a simple additive calculation would predict. The body, it seems, is constantly negotiating with itself, adjusting and reallocating energy in ways that prioritize balance over excess.

The researchers emphasized that 28% is an average. Individual responses varied widely. Some bodies compensated more, others less. There is no single rule that applies to everyone, only a shared tendency toward constraint.

In their own words, “Humans and other animals respond to increased physical activity by reducing energy expenditure on other tasks, supporting a constrained model of energy expenditure.”

Why Weight Loss Often Feels So Stubborn

Seen through this lens, a familiar frustration begins to make sense. If exercise burns calories but also triggers compensation, then its impact on weight loss is naturally limited.

This does not mean exercise is ineffective or pointless. It means the body is not a passive recipient of our efforts. It is an active participant, constantly adapting to changes in activity levels.

When someone starts exercising more, the expected surge in daily calorie burn may be softened by subtle reductions elsewhere. The scale may move more slowly than hoped, or barely at all. The effort feels real, but the payoff seems smaller than promised.

This dynamic also helps explain why diet plays such a central role in weight loss. Food intake directly affects energy balance in a way that the body cannot fully offset through internal adjustments. Exercise, by contrast, enters a complex negotiation with the body’s existing energy budget.

Rethinking What Exercise Is Really For

The study does not argue against exercise. It simply reframes what exercise can reasonably be expected to do.

Exercise still increases total energy use. It still supports overall health in countless ways beyond calorie burning. But when it comes to weight loss, its effects may be more modest than traditional formulas suggest.

Understanding this can be oddly freeing. It shifts the conversation away from personal failure and toward biological reality. If weight loss stalls despite consistent effort, it may not be a lack of discipline. It may be the body doing exactly what it evolved to do: protect its energy balance.

This perspective invites a gentler, more informed approach to health. One that recognizes the body as a responsive system, not a simple machine.

Why This Research Truly Matters

At its heart, this research matters because it challenges a deeply rooted assumption and replaces it with something more honest and humane.

By showing that energy expenditure follows a constrained model, the study helps explain why exercise alone often leads to less weight loss than expected. It clarifies why frustration is common and why dietary choices remain so influential.

More importantly, it reshapes expectations. When people understand that the body compensates for increased activity, they can set goals that are grounded in reality rather than disappointment. Exercise can be valued for strength, mobility, endurance, and well-being, not just as a tool for shrinking numbers on a scale.

Science does not always deliver dramatic revolutions. Sometimes it offers something quieter but just as powerful: an explanation that makes our lived experiences finally make sense. In revealing how the body balances its energy behind the scenes, this study does exactly that.

Study Details

Herman Pontzer et al, The evidence for constrained total energy expenditure in humans and other animals, Current Biology (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2026.01.025