For someone living with panic disorder, fear does not always announce itself politely. It can erupt in an instant, flooding the body with a racing heart, breath that suddenly feels too small, dizziness, blurred vision, and an overwhelming sense that something is terribly wrong. These episodes, known as panic attacks, can strike repeatedly and unpredictably. Across the world, an estimated 2–3% of people will experience panic disorder at some point in their lives, making it far from rare, yet still deeply misunderstood.

For years, scientists have tried to understand what is happening inside the brain during this disorder. Why does fear spiral so quickly? Why does the body react as if danger is imminent, even when there is none? The answers have been elusive, in part because most studies have looked at only small groups of people. Small samples can whisper hints, but they struggle to tell a clear, reliable story.

Now, a global collaboration of researchers has taken a much bigger look at the brain, and what they found offers a clearer, more consistent picture of how panic disorder leaves its imprint on neural structure.

A Worldwide Effort to See the Bigger Picture

The new study, led by scientists at Amsterdam University Medical Center, Leiden University, and many collaborating institutes, did something rare in psychiatric research. Instead of examining dozens or even a few hundred brains, the team pooled brain scans from nearly 5,000 people around the world. Among them were about 1,100 individuals diagnosed with panic disorder and roughly 3,800 people with no known psychiatric diagnoses, spanning ages 10 to 66.

This massive dataset was made possible through the ENIGMA Anxiety Working Group, a global initiative designed to harmonize data and methods across many research teams. By using standardized protocols and shared analytical tools, the researchers aimed to overcome one of the biggest challenges in neuroscience: inconsistency.

As first author Laura K. M. Han and senior author Moji Aghajani explained, previous studies often struggled to replicate one another. The question lingered whether observed brain differences were truly part of panic disorder or simply artifacts of small sample sizes. This new approach was designed to provide the most reliable test yet.

Inside the Brain Scanner

Every participant’s brain was examined using magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, a familiar tool in hospitals and research labs alike. MRI does not peer into thoughts or emotions directly, but it allows scientists to measure the physical structure of the brain with remarkable precision.

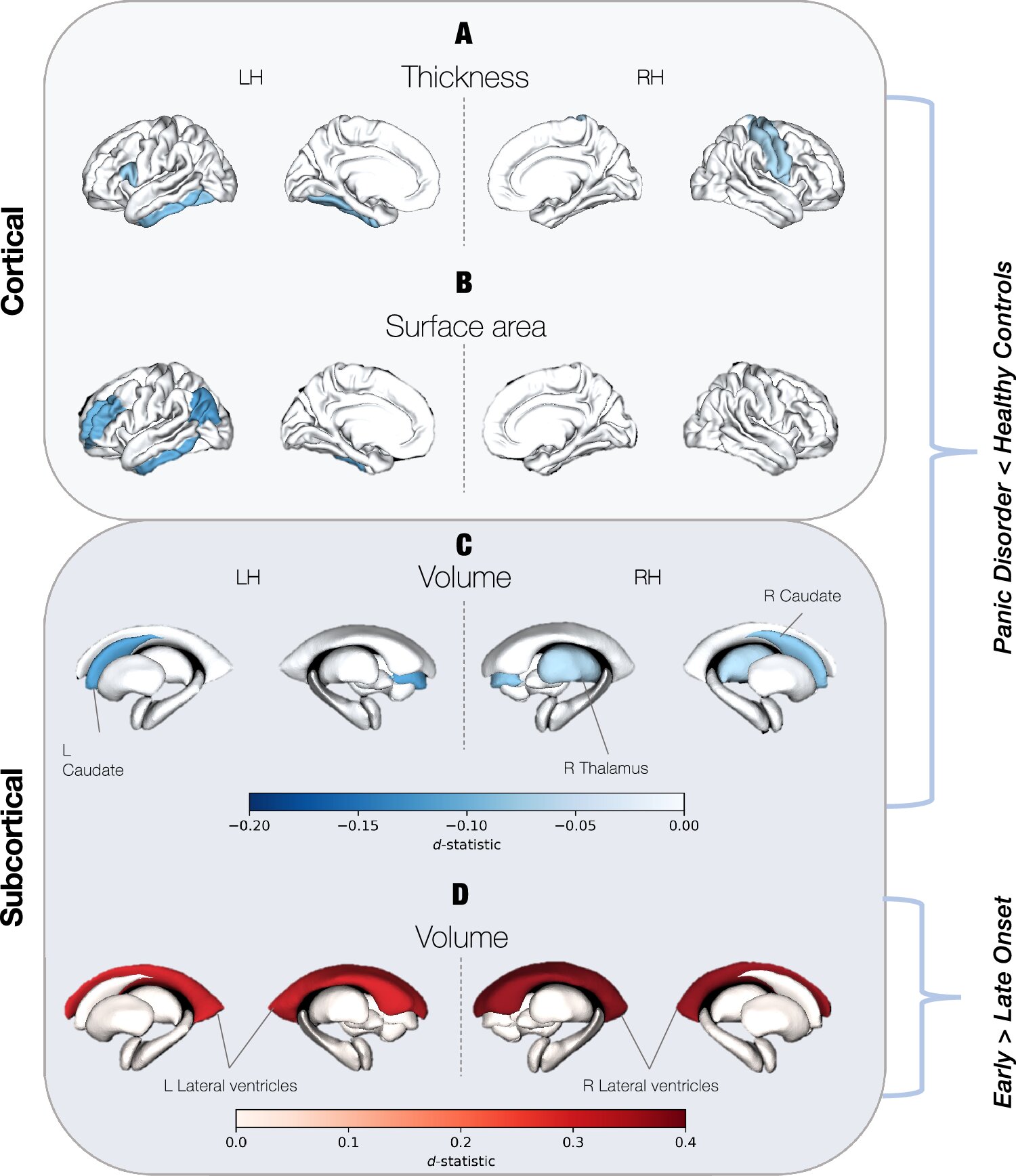

Using harmonized ENIGMA protocols and the FreeSurfer brain segmentation software, the team measured cortical thickness, cortical surface area, and subcortical volumes. These metrics describe how thick the outer layer of the brain is, how much surface area different regions cover, and the size of deeper brain structures.

Advanced statistical models then compared people with panic disorder to healthy control subjects, carefully accounting for differences in age, sex, and even the scanning site where the MRI was collected. This attention to detail ensured that the patterns they found were not simply due to technical quirks or demographic differences.

Subtle Changes That Speak Volumes

When the analyses were complete, the results revealed a quiet but consistent signal. People with panic disorder tended to have a slightly thinner cortex compared to those without the disorder. Certain regions of the brain also showed reduced surface area or smaller volume.

These differences were not dramatic or obvious at a glance. Instead, they were subtle, spread across key areas of the brain. The frontal, temporal, and parietal regions showed consistent reductions, as did subcortical structures such as the thalamus and caudate.

What makes these findings meaningful is not their size, but their consistency. Across thousands of brains, collected in many countries, the same pattern emerged again and again. This suggests that panic disorder is associated with reliable neuroanatomical features, even if those features are small.

The Brain’s Emotional Control Rooms

The regions identified in the study are deeply involved in how the brain handles emotion. They help determine how emotionally important information is perceived, how it is processed, and how the body ultimately responds.

In everyday life, these systems help us notice danger, regulate fear, and return to calm once a threat has passed. In panic disorder, this balance appears to be disrupted. The newly identified structural differences offer physical clues that align with long-standing models of the disorder, which propose that emotional regulation networks are altered.

The researchers also found that some of these brain differences are age-dependent, suggesting that panic disorder may interact with brain development and aging in complex ways.

When Panic Begins Early

One of the most intriguing findings emerged when the team looked at age of onset. Individuals whose panic disorder began before age 21 showed a specific structural feature: larger lateral ventricles, fluid-filled spaces within the brain.

This association hints that early-onset panic disorder may follow a somewhat different neurodevelopmental path than cases that emerge later in life. While the study does not explain why this happens, it highlights the importance of considering when symptoms first appear, not just whether they are present.

The Power of Big Data in Mental Health

Beyond panic disorder itself, the study sends a broader message about how psychiatric research can move forward. By pooling data on a global scale, researchers were able to detect subtle brain differences that might remain invisible in smaller studies.

This same large-scale approach has already been applied to other conditions, including generalized anxiety disorder, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance use disorders. Each time, the lesson is similar: mental health conditions often leave faint but meaningful traces in the brain, and seeing them clearly requires many eyes and many brains.

Looking Toward the Future of Understanding

The authors emphasize that their findings are not an endpoint. Instead, they provide a foundation for deeper exploration. Future studies could follow individuals with panic disorder over time, tracking how brain structure changes with development, aging, or treatment.

There is also the possibility of integrating genetic and environmental risk factors, or combining structural imaging with studies of how brain regions function and communicate. Rather than focusing solely on diagnostic labels, researchers may begin linking brain differences to prognosis, treatment response, or even prevention strategies.

Why This Research Matters

Panic disorder can be terrifying, isolating, and life-altering. Understanding that it is associated with measurable, consistent differences in brain structure helps move the conversation away from blame and misunderstanding. It reinforces the idea that panic disorder is not a failure of will or character, but a condition with real biological underpinnings.

By mapping these subtle brain signatures with unprecedented clarity, this research brings science one step closer to understanding how panic takes hold, why it persists, and how it might one day be better treated. For the millions of people worldwide who live with sudden, overwhelming fear, that progress matters deeply.

Study Details

Laura K. M. Han et al, Structural brain differences associated with panic disorder: an ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group mega-analysis of 4924 individuals worldwide, Molecular Psychiatry (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03376-4.