Imagine waking up one morning and forgetting where you placed your keys. Now imagine forgetting the route to your home, the names of your children, or even the face that stares back at you in the mirror. This slow erosion of identity is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease—a condition as mysterious as it is devastating.

Alzheimer’s disease is not just forgetfulness or aging catching up with someone. It is a complex neurodegenerative disorder that strips away memory, cognition, independence, and eventually, life itself. From the bustling labs of neuroscientists to the quiet rooms of caregivers, Alzheimer’s represents one of the greatest medical, emotional, and societal challenges of our time.

In this in-depth article, we explore Alzheimer’s disease from a medical perspective—its biology, progression, diagnosis, treatment, and the future of research—while weaving in the human element that makes this disorder one of the most feared and studied in modern medicine.

The History of Alzheimer’s: From Discovery to Modern Day

The story begins in 1906 when German psychiatrist Dr. Alois Alzheimer presented the case of a 51-year-old woman named Auguste Deter. She had exhibited confusion, memory loss, paranoia, and deteriorating language skills. After her death, Alzheimer examined her brain under a microscope and found two abnormal structures—what we now know as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

This moment marked the formal discovery of Alzheimer’s disease, a condition that was initially considered rare. Over the next century, it would become one of the most prevalent neurological disorders in the world.

By the late 20th century, as life expectancy increased and aging populations grew, Alzheimer’s emerged from obscurity to become a public health crisis. Research exploded in the 1980s and 90s, and terms like “beta-amyloid,” “tau protein,” and “cholinergic hypothesis” became central to the scientific discussion.

Today, Alzheimer’s disease affects over 50 million people worldwide, with millions more at risk. It is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of cases, and is now seen not just as a brain disorder but as a systemic, age-related condition influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

Understanding the Brain: Anatomy and Function

To grasp Alzheimer’s, one must first understand the brain’s basic architecture. The human brain is a marvel of biological engineering, composed of around 86 billion neurons. These neurons communicate via synapses, transmitting signals through electrochemical impulses.

Key regions involved in Alzheimer’s include:

- Hippocampus: Central to memory formation and spatial navigation.

- Cerebral Cortex: Responsible for thinking, reasoning, and decision-making.

- Amygdala: Involved in emotional responses.

- Basal forebrain: Houses cholinergic neurons essential for attention and learning.

Each of these areas becomes compromised as Alzheimer’s progresses. What begins as subtle memory lapses gradually evolves into widespread cognitive and functional decline.

The Pathophysiology: What Happens in the Alzheimer’s Brain?

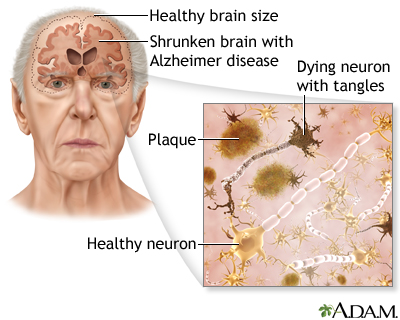

At its core, Alzheimer’s disease is marked by the accumulation of toxic proteins in and around neurons, leading to cell death and brain atrophy. Two key pathological features define the disease:

Amyloid Plaques

These are clumps of beta-amyloid peptide, a fragment of a larger protein known as amyloid precursor protein (APP). When APP is improperly cleaved by enzymes (beta-secretase and gamma-secretase), sticky beta-amyloid peptides are formed.

These peptides aggregate outside neurons and form plaques. While the exact role of plaques is still debated, they appear to disrupt cell-to-cell communication, trigger inflammatory responses, and contribute to neurodegeneration.

Neurofibrillary Tangles

These are twisted fibers of a protein called tau. Normally, tau stabilizes microtubules—structures that help transport nutrients within neurons. In Alzheimer’s, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated and clumps together, forming tangles inside neurons.

Tangles disrupt intracellular transport, leading to cell dysfunction and death. Together with amyloid plaques, they are considered the “twin pillars” of Alzheimer’s pathology.

Neuroinflammation and Immune Response

Microglia, the brain’s immune cells, respond to the accumulation of plaques and tangles. While initially protective, chronic activation leads to inflammation, oxidative stress, and further neuron loss.

Loss of Neurotransmitters

One of the earliest and most consistent findings in Alzheimer’s is the loss of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain. These neurons produce acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter essential for learning and memory.

Other neurotransmitters like serotonin, glutamate, and norepinephrine are also affected as the disease progresses.

The Stages of Alzheimer’s: From Mild to Severe

Alzheimer’s does not manifest all at once. It unfolds over years, progressing through distinct stages:

Preclinical Stage

This stage can last for a decade or more. There are no obvious symptoms, but changes in the brain—such as amyloid deposition and tau accumulation—have already begun. New biomarker tests can sometimes detect these changes even before symptoms appear.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

Individuals with MCI experience noticeable memory lapses but can still function independently. MCI does not always progress to Alzheimer’s, but it significantly increases the risk.

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease

Symptoms include difficulty remembering recent events, repeating questions, and trouble with planning or organizing. Patients may get lost in familiar places or struggle with word-finding.

Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease

At this stage, cognitive decline deepens. Patients may forget personal history, fail to recognize close friends or family, and need help with daily activities like dressing or bathing. Behavioral changes—agitation, wandering, delusions—are common.

Severe Alzheimer’s Disease

The final stage is marked by profound memory loss, speech difficulties, incontinence, immobility, and complete dependence on caregivers. Eventually, the brain’s control of vital functions breaks down, and death occurs, often from complications like infections.

Risk Factors and Causes

While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s is not fully understood, several risk factors have been identified:

Age

The most significant risk factor. After age 65, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s doubles every five years.

Genetics

The APOE-e4 allele is the most well-known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s. People with one copy have an increased risk; those with two copies have an even higher risk.

Early-onset Alzheimer’s (before age 65) is often linked to mutations in genes like APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2, though it is rare.

Lifestyle and Cardiovascular Health

Factors like obesity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and lack of exercise are associated with higher Alzheimer’s risk. What’s good for the heart is often good for the brain.

Education and Cognitive Reserve

People with higher levels of education or lifelong intellectual engagement seem to have a “cognitive reserve” that protects against symptoms.

Head Trauma and Toxins

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) from repeated head injuries can lead to Alzheimer-like pathology. Exposure to heavy metals, pesticides, and air pollution may also increase risk.

Diagnosis: Peering into the Mind

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s is challenging, especially in its early stages. Physicians rely on a combination of tools:

Clinical Evaluation

A detailed medical history, family history, and symptom timeline are crucial. Cognitive tests like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) evaluate memory, language, attention, and spatial skills.

Imaging

- MRI scans detect brain atrophy.

- PET scans can visualize amyloid plaques and tau tangles using radioactive tracers.

- FDG-PET measures glucose metabolism in the brain, revealing functional decline.

Biomarkers

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis for beta-amyloid, total tau, and phosphorylated tau.

- Blood tests for beta-amyloid and phosphorylated tau are becoming increasingly accurate and accessible.

Differential Diagnosis

Doctors must rule out other causes of dementia, including vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, depression, vitamin deficiencies, and thyroid dysfunction.

Treatment Options: Slowing the Clock

There is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s. However, several treatments aim to manage symptoms and slow progression:

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

These drugs (e.g., donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) increase levels of acetylcholine in the brain and provide modest improvement in cognition and behavior.

NMDA Receptor Antagonists

Memantine blocks excess glutamate activity, which may protect neurons from excitotoxicity.

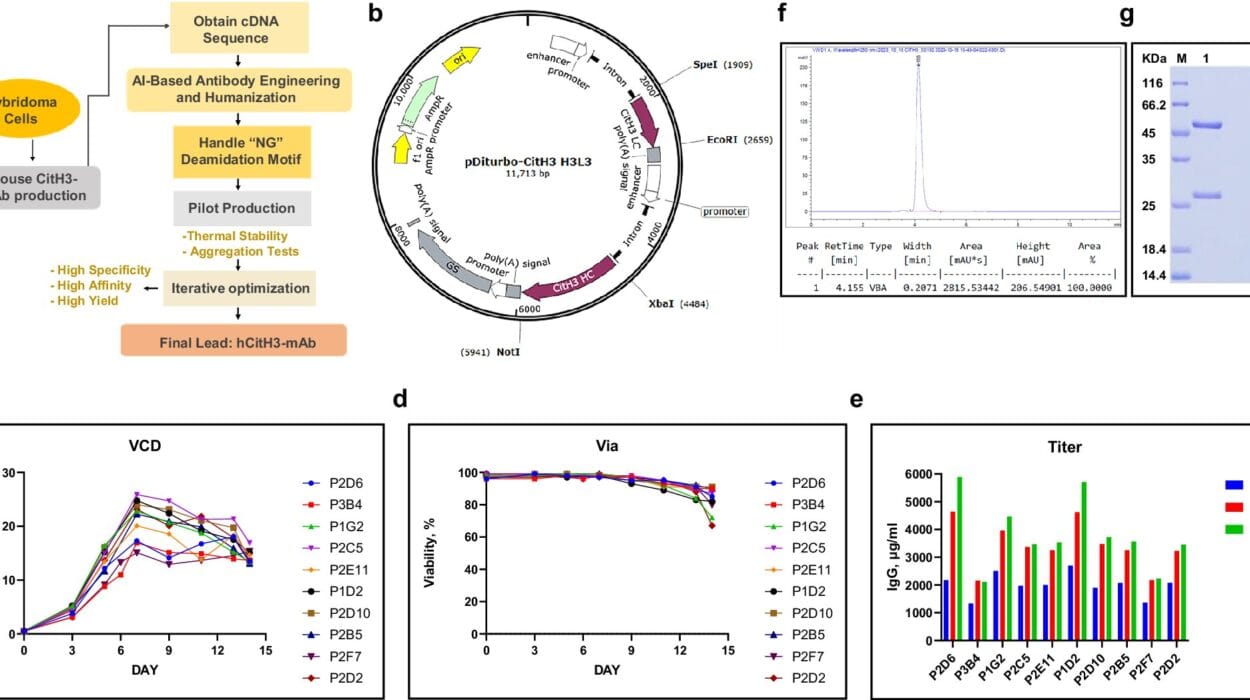

Disease-Modifying Therapies

In recent years, monoclonal antibodies like aducanumab and lecanemab have been approved. These drugs target amyloid plaques and are designed to slow progression, although their clinical benefit remains a subject of debate.

Symptom Management

Antidepressants, antipsychotics, sleep aids, and anxiolytics may be used cautiously to manage symptoms like depression, agitation, and insomnia.

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Cognitive training, physical activity, music therapy, and occupational therapy can enhance quality of life and reduce behavioral symptoms.

Caregiving and Family Support: The Hidden Toll

Alzheimer’s doesn’t just affect the patient—it impacts everyone around them. Families often become the primary caregivers, facing emotional, physical, and financial challenges.

Caregiver burden is real. It includes:

- Grief over the “loss” of a loved one while they are still alive.

- Exhaustion from round-the-clock supervision.

- Isolation from social circles.

- Financial strain from medical and long-term care expenses.

Support groups, counseling, respite care, and community programs are vital resources for caregivers. Governments and healthcare systems must recognize the enormous unpaid labor of Alzheimer’s caregivers and offer structured support.

The Global Impact: An Aging Crisis

As global life expectancy rises, Alzheimer’s disease is becoming a major public health concern. According to estimates:

- A new case of dementia is diagnosed every 3 seconds.

- By 2050, over 150 million people worldwide may be living with Alzheimer’s or related dementias.

- The global cost exceeds $1 trillion annually and continues to climb.

This is not just a medical issue—it’s an economic and social one. Countries must prepare their healthcare infrastructures, insurance models, and elder care policies to meet the demands of this growing crisis.

The Future of Alzheimer’s Research: Hope on the Horizon

While a cure remains elusive, the pace of Alzheimer’s research has never been faster. Key areas of innovation include:

Early Detection and Biomarkers

Advances in blood tests and imaging may allow for routine screening before symptoms appear, enabling early intervention.

Anti-Amyloid and Anti-Tau Therapies

Next-generation drugs aim to remove plaques and tangles more effectively and safely, possibly in combination with other treatments.

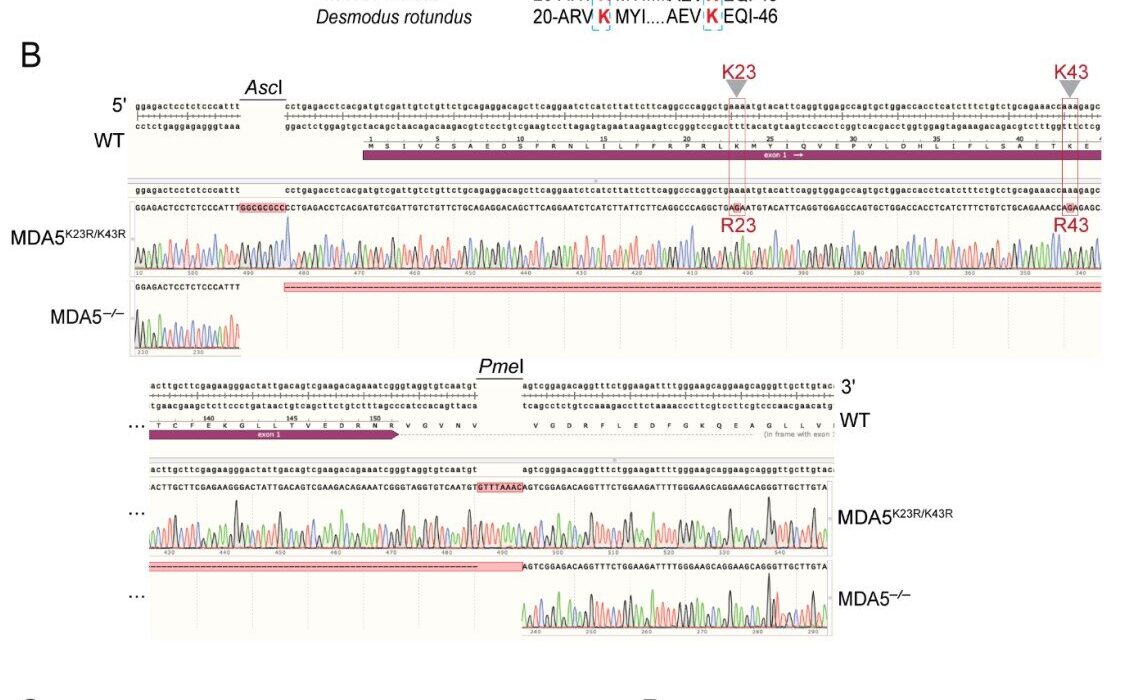

Gene Therapy and CRISPR

Targeted genetic therapies may one day correct faulty genes or enhance protective ones.

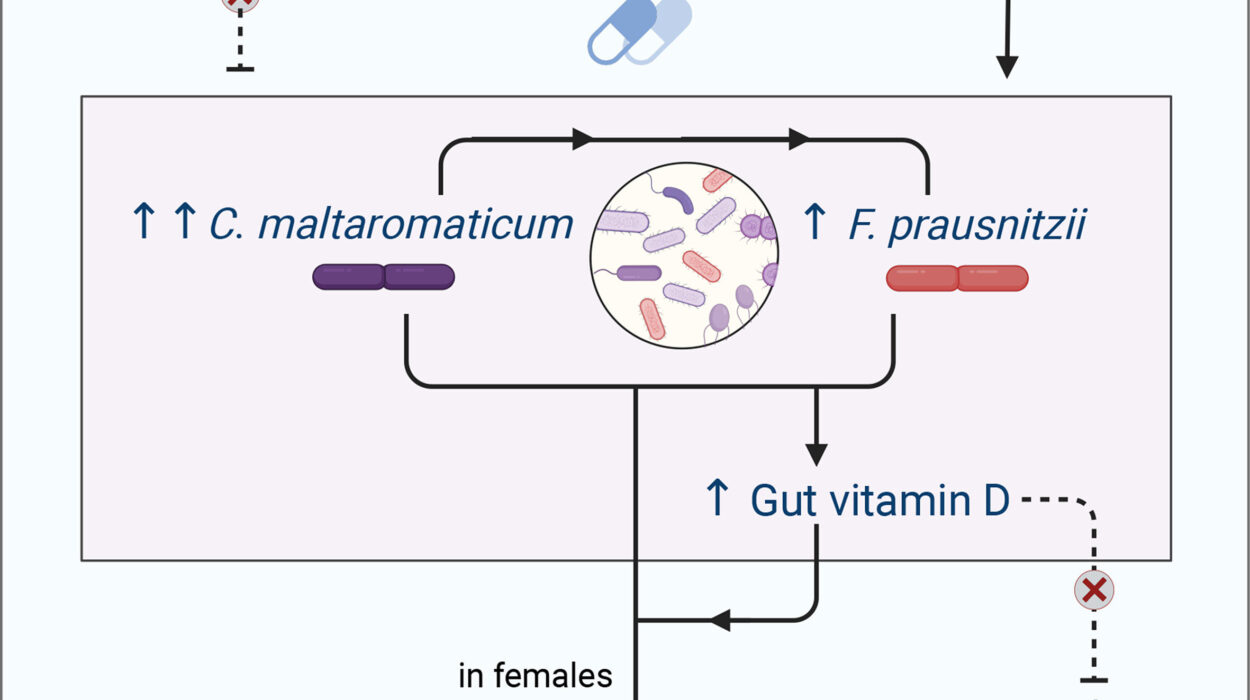

Neuroinflammation Modulation

Drugs that regulate the immune system and reduce inflammation in the brain show promise in slowing progression.

Brain-Computer Interfaces and Neurostimulation

Tech like deep brain stimulation and neural implants may help restore function or slow decline.

Lifestyle and Prevention Research

Diet, exercise, sleep, and cognitive engagement remain critical areas of study. The FINGER study and other trials are exploring how lifestyle interventions can delay or prevent cognitive decline.

Conclusion: Holding On to Memory

Alzheimer’s disease is a thief. It robs individuals of their memories, relationships, and autonomy. It shakes families and burdens societies. But it is also a puzzle—a biological riddle that we are slowly, piece by piece, beginning to solve.

Through science, compassion, and collective effort, we move closer to a world where Alzheimer’s is no longer a sentence, but a solvable problem. Until then, our greatest tools remain early detection, empathy, support, and relentless curiosity.

Alzheimer’s reminds us of the fragility of memory—and the enduring power of love. It is both a medical challenge and a human story, one that touches millions, and demands that we remember not just those who suffer, but the fight to heal them.