Sleep is supposed to be the most natural thing in the world. You lie down, close your eyes, and drift away. Yet for millions of people, night after night becomes a battlefield. The body is exhausted, the eyes burn with fatigue, but the mind refuses to slow down. Thoughts race, worries echo, memories replay, and time stretches painfully between glances at the clock. This is insomnia, and at its core often lies a brain that cannot power down—a hyperaroused brain that remains stuck in a state of alertness long after the day has ended.

Insomnia is not simply “bad sleep.” It is an experience that reshapes how people feel, think, and live. It erodes confidence, dulls joy, and can make the night feel hostile rather than restorative. Understanding insomnia requires going beyond surface explanations and into the deeper biology of arousal, threat, and survival. The hyperarousal brain is not broken; it is doing exactly what evolution trained it to do—stay awake when it senses danger. The tragedy is that, in insomnia, the danger is often invisible and internal.

The Nighttime Paradox of Exhaustion and Alertness

One of the most confusing aspects of insomnia is the contradiction it creates. The body is tired, sometimes desperately so, yet the brain behaves as if it must stay vigilant. Muscles may ache with fatigue, eyelids may feel heavy, but the mind is sharp, busy, and alert. This paradox is not imaginary, nor is it a failure of willpower. It reflects a real and measurable state of heightened arousal in the nervous system.

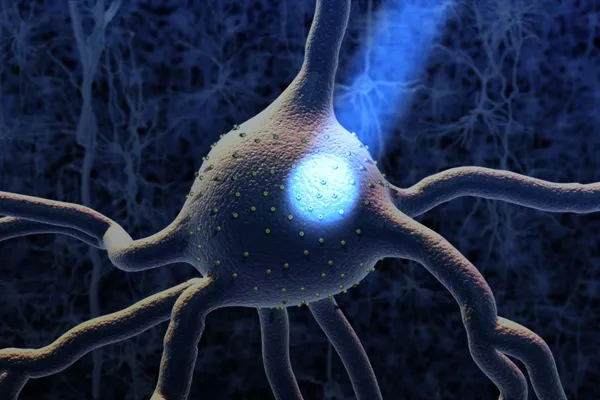

In healthy sleep, the brain gradually shifts from wakefulness into a quieter mode. Neural activity slows, stress hormones decline, and the balance tips toward relaxation. In insomnia, this shift is disrupted. Brain imaging studies have shown that people with chronic insomnia often maintain higher levels of brain activity even during periods that should be restful. Regions involved in thinking, emotion, and self-monitoring remain unusually active, as if the brain is standing guard.

This hyperarousal is not limited to the mind alone. The body often mirrors it. Heart rate may stay elevated, body temperature may remain slightly higher than normal, and stress-related hormones like cortisol may fail to drop at night as they should. Together, these changes create an internal environment that is incompatible with deep, restorative sleep.

Arousal as a Survival Mechanism

To understand why the brain becomes hyperaroused, it helps to remember what arousal is for. Arousal is not an enemy; it is a survival tool. It prepares the body to respond to threats, focus attention, and mobilize energy. When danger is present, sleep is risky. Evolution favored brains that could stay awake when necessary, even if the body was tired.

The problem arises when the brain mistakenly interprets harmless situations as threatening. For someone with insomnia, bedtime itself can become a signal of danger. Past experiences of lying awake, feeling helpless, and dreading another sleepless night condition the brain to associate the bed with frustration and anxiety. Over time, the mere act of going to bed can trigger arousal.

This process is subtle and often unconscious. The person may consciously want to sleep, but their brain has learned a different lesson: nighttime equals struggle. The hyperarousal brain is not disobedient; it is protective, acting on learned associations and perceived risks.

The Role of Stress and Modern Life

Modern life places extraordinary demands on the brain. Constant stimulation, relentless schedules, and social pressures keep arousal levels high throughout the day. For many people, there is little opportunity for true mental rest. Emails, notifications, and worries follow us into the evening, blurring the boundary between day and night.

Chronic stress is a powerful driver of hyperarousal. When stress systems are activated repeatedly, they can become overly sensitive. The brain begins to anticipate threats even when none are present. This anticipation keeps stress circuits active, making it difficult to relax when the external demands finally subside.

Insomnia often begins during periods of acute stress, such as illness, work pressure, or emotional upheaval. For some, sleep returns to normal once the stress resolves. For others, the brain remains stuck in a heightened state, having learned to stay alert at night. What began as a temporary response becomes a persistent pattern.

The Brain Circuits That Refuse to Rest

Sleep and wakefulness are regulated by a complex network of brain regions that balance arousal and inhibition. In healthy sleep, systems that promote wakefulness gradually quiet down, while sleep-promoting systems gain influence. In insomnia, this balance is disrupted.

Key arousal systems involve neurotransmitters that increase alertness and attention. These systems are designed to keep the brain responsive to the environment. In people with insomnia, these systems often remain overactive at night. At the same time, systems that promote sleep may struggle to assert control.

Emotion-processing regions of the brain also play a crucial role. The brain areas involved in detecting threat and regulating emotion can become overly engaged, especially in individuals who tend to worry or ruminate. This emotional arousal feeds cognitive activity, creating a loop in which thoughts and feelings amplify each other.

Importantly, this is not simply a matter of “thinking too much.” Even when thoughts are not consciously racing, the brain may remain physiologically alert. Some people with insomnia report feeling strangely awake even when their minds feel blank, reflecting arousal at a deeper neural level.

Why Trying Harder Makes Sleep Worse

One of the cruel ironies of insomnia is that effort often backfires. The harder someone tries to sleep, the more elusive sleep becomes. This happens because effort itself is a form of arousal. Trying to force sleep activates attention, monitoring, and control—all processes associated with wakefulness.

People with insomnia often become hyper-aware of their sleep. They monitor how tired they feel, how long it takes to fall asleep, and how many times they wake during the night. This constant self-observation keeps the brain engaged. Instead of drifting into sleep, the mind remains focused on performance.

Fear of the consequences of poor sleep further fuels this cycle. Worries about functioning the next day, health effects, or long-term damage add emotional intensity to the night. The bed becomes a place of evaluation rather than rest, reinforcing hyperarousal.

The Emotional Toll of the Sleepless Night

Insomnia is not just a nighttime problem. Its emotional impact spills into every part of life. Persistent sleep loss can heighten emotional reactivity, making people more sensitive to stress and less resilient in the face of challenges. Small problems feel overwhelming, and joy can feel muted or distant.

Over time, insomnia can erode a person’s sense of self. Confidence suffers when basic functioning feels unreliable. Social relationships may strain as irritability and fatigue accumulate. The night, once associated with comfort, becomes a source of dread.

The hyperarousal brain contributes to this emotional burden by maintaining a state of vigilance even during the day. Many people with chronic insomnia report feeling “wired but tired,” unable to fully relax even when awake. This constant tension drains emotional resources and reinforces the cycle of poor sleep.

Insomnia Is Not Just in the Mind

It is important to emphasize that insomnia is not imaginary or purely psychological. The hyperarousal state has measurable biological markers. Studies have shown differences in brain metabolism, hormone levels, and autonomic nervous system activity in people with insomnia compared to good sleepers.

These findings validate the lived experience of those who struggle with sleep. Insomnia is not a failure of discipline or a lack of gratitude for rest. It is a real condition rooted in how the brain and body regulate arousal.

At the same time, insomnia is deeply influenced by thoughts, emotions, and learning. Biology and psychology are intertwined. Understanding insomnia requires respecting both the physical reality of hyperarousal and the personal experiences that shape it.

The Quiet Hours and the Amplified Mind

Nighttime has a unique psychological quality. When the world grows quiet, the mind often grows louder. Distractions fade, and attention turns inward. For someone with insomnia, this inward focus can amplify worries that were manageable during the day.

The brain’s threat-detection systems are particularly sensitive to uncertainty, and nighttime offers little reassurance. Problems feel unsolvable in the dark, and concerns about the future can spiral. The hyperarousal brain treats these thoughts as signals to stay alert.

This amplification is not a sign of weakness. It reflects how the brain processes information in the absence of external input. When arousal systems are already heightened, the quiet of night becomes fertile ground for rumination.

The Misconception of “Turning the Mind Off”

People often describe insomnia as an inability to “turn the mind off,” but this phrase can be misleading. The brain does not have an off switch. Sleep is not the absence of mental activity but a different mode of functioning. Even during deep sleep, the brain remains active in organized ways.

In insomnia, the problem is not that the brain refuses to shut down, but that it remains in a mode designed for interaction with the world. Attention stays outward or self-focused, emotions remain engaged, and monitoring continues. Sleep requires a shift toward disengagement, not suppression.

Trying to force the mind into silence often increases frustration and arousal. A more helpful perspective is learning how to allow the brain to shift modes naturally, without pressure or struggle.

Learned Insomnia and the Power of Association

Insomnia often becomes self-sustaining through learning. The brain is highly sensitive to patterns and associations. If lying in bed repeatedly leads to frustration, anxiety, or alertness, the brain learns that the bed is not a safe place to relax.

This learning can happen quickly. Even a few nights of poor sleep can create anticipatory anxiety. Over time, the conditioned response strengthens. The hyperarousal brain reacts automatically, even before conscious thought.

This does not mean insomnia is permanent. Learned associations can be unlearned. However, it explains why insomnia can persist long after the original trigger has passed.

The Role of Personality and Temperament

Certain personality traits and temperamental factors can increase vulnerability to hyperarousal. People who are naturally vigilant, conscientious, or sensitive to threat may be more prone to insomnia. High levels of responsibility and self-monitoring, while valuable in many areas of life, can become liabilities at night.

Perfectionism can also play a role. When sleep becomes something that must be achieved correctly, pressure builds. The bed turns into a performance arena, and the brain responds with heightened alertness.

These traits do not cause insomnia on their own, but they can shape how the brain responds to stress and sleep disruption. Recognizing these patterns can help individuals approach sleep with greater self-compassion.

Insomnia Across the Lifespan

Insomnia can occur at any age, but its expression may change over time. In younger individuals, it often involves difficulty falling asleep due to racing thoughts. In older adults, it may present more as frequent awakenings or early morning waking.

Age-related changes in sleep regulation can interact with hyperarousal. As sleep becomes lighter with age, the brain may be more easily disrupted by arousal signals. At the same time, life experiences accumulate, providing more material for nighttime rumination.

Despite these differences, the core mechanism of hyperarousal remains relevant across the lifespan. Understanding this continuity helps unify diverse insomnia experiences under a common framework.

The Impact on Physical Health

Chronic insomnia does not exist in isolation from the rest of the body. Persistent hyperarousal can strain multiple physiological systems. Elevated stress hormones and disrupted sleep can affect immune function, metabolism, and cardiovascular health.

While occasional poor sleep is a normal part of life, long-term insomnia is associated with increased risk for various health problems. This does not mean that insomnia inevitably leads to disease, but it underscores the importance of addressing it seriously.

The relationship between insomnia and health is complex and bidirectional. Physical conditions can disrupt sleep, and poor sleep can worsen physical symptoms. Hyperarousal often sits at the center of this interaction, amplifying both sleep and health challenges.

Rethinking Rest and Recovery

One of the most painful aspects of insomnia is the feeling that rest is impossible. Even when lying still, the mind remains busy, and the body feels tense. This leads many people to believe that if they cannot sleep, they cannot recover.

In reality, the body can experience degrees of rest even without full sleep. Quiet wakefulness, reduced stimulation, and gentle disengagement can all contribute to recovery. While they do not replace sleep, they can reduce the sense of desperation that fuels hyperarousal.

Changing the relationship with rest can be a powerful step in calming the hyperarousal brain. When the night is no longer viewed as a total failure, pressure eases, and the conditions for sleep improve.

Hope in Understanding

Perhaps the most important message for anyone struggling with insomnia is that hyperarousal is understandable and reversible. The brain is adaptable. Just as it learned to stay alert at night, it can relearn how to feel safe enough to sleep.

Understanding insomnia as a state of hyperarousal rather than a personal failing shifts the emotional landscape. It replaces self-blame with curiosity. Instead of asking, “What is wrong with me?” the question becomes, “What is my brain trying to protect me from?”

This shift opens the door to change. When fear and frustration decrease, arousal systems quiet. Sleep is not forced; it is invited.

The Quiet Return of Sleep

Sleep rarely returns with a dramatic flourish. More often, it comes back gradually, almost unnoticed at first. A shorter night here, a deeper stretch there. As the brain learns that the night is no longer a threat, hyperarousal softens.

This process requires patience. The same learning mechanisms that sustain insomnia also ensure that change takes time. Each night of reduced struggle teaches the brain a new lesson. Over time, these lessons accumulate.

Sleep, in the end, is not something we conquer. It is something we allow. The hyperarousal brain, once reassured, remembers how to rest.

Living With the Knowledge of the Hyperarousal Brain

Understanding the hyperarousal brain does not eliminate insomnia overnight, but it changes how one relates to it. Knowledge brings perspective. It transforms sleeplessness from a mysterious enemy into a meaningful signal.

Insomnia becomes a message about stress, safety, and balance. Listening to that message with compassion rather than panic can soften its impact. The brain is not sabotaging rest; it is reacting to perceived need.

When this understanding takes root, nights may still be difficult, but they are less frightening. And in that reduced fear, sleep often finds its way back.

A Final Reflection on Wakefulness and Humanity

Insomnia exposes something deeply human. It reveals how closely sleep is tied to feeling safe, how sensitive the brain is to experience, and how difficult it can be to let go. The hyperarousal brain is not a flaw in our design; it is a reflection of our capacity to care, anticipate, and protect.

In a world that rarely slows down, it is not surprising that many brains struggle to rest. Insomnia reminds us that rest is not just a biological function but an emotional and psychological state.

Understanding why you cannot turn your mind off is not about fixing a broken system. It is about gently guiding a vigilant brain back toward trust. In that trust, sleep becomes possible again, not as an achievement, but as a natural return to balance.