Caffeine is so deeply woven into modern life that many people rarely pause to consider its effects on the brain. It arrives quietly each morning in a cup of coffee or tea, hides in chocolate and soft drinks, and fuels long nights of study or work through energy drinks. Because it is legal, socially accepted, and widely consumed, caffeine often feels less like a psychoactive substance and more like a simple habit. Yet from a neuroscientific perspective, caffeine is a powerful drug that alters brain chemistry, neural signaling, and even emotional regulation. When caffeine use stops, the brain does not remain indifferent. Instead, it undergoes a complex and often uncomfortable process of readjustment.

Quitting caffeine is not merely about missing a familiar taste or routine. It is a biological event that unfolds inside the brain over hours, days, and sometimes weeks. Neural receptors shift their behavior, blood flow changes, neurotransmitter systems recalibrate, and psychological states fluctuate. These changes explain why people who stop caffeine often experience headaches, fatigue, irritability, and brain fog. At the same time, they also explain why many individuals eventually report deeper sleep, more stable energy, and improved emotional balance after withdrawal has passed.

Understanding what happens to the brain when caffeine is removed requires looking closely at how caffeine works in the first place. Only then does the withdrawal process make sense as a predictable, scientifically grounded response rather than a personal weakness or lack of willpower.

Caffeine and the Brain’s Chemistry of Wakefulness

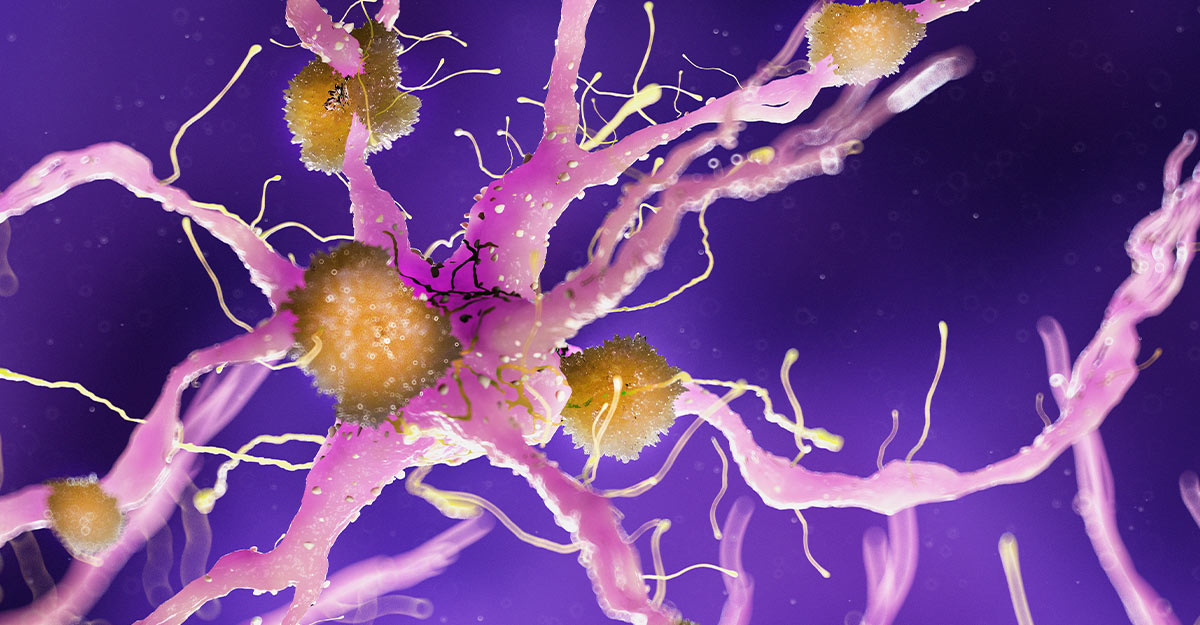

At its core, caffeine exerts its effects by interfering with a neurotransmitter called adenosine. Adenosine is a naturally occurring chemical in the brain that accumulates throughout the day as neurons consume energy. As adenosine levels rise, they bind to specific receptors on neurons, signaling fatigue and promoting sleepiness. This process is one of the brain’s fundamental ways of tracking how long it has been awake and how much rest it needs.

Caffeine closely resembles adenosine at the molecular level. Because of this similarity, caffeine can bind to adenosine receptors without activating them. When caffeine occupies these receptors, it blocks adenosine from delivering its message of tiredness. The result is a state of artificial alertness. The brain is still producing adenosine, but its signal is temporarily silenced.

This blockade does not only reduce sleepiness. By preventing adenosine from exerting its calming influence, caffeine indirectly increases the activity of other neurotransmitters. Dopamine signaling becomes more pronounced, contributing to improved mood and motivation. Norepinephrine and acetylcholine activity rise, sharpening attention and reaction time. The brain enters a state of heightened arousal that feels productive, focused, and mentally energized.

With regular caffeine consumption, however, the brain adapts. Neural systems are designed to maintain balance, and when a chemical repeatedly disrupts that balance, compensatory changes follow. These adaptations are central to understanding what happens when caffeine use suddenly stops.

Brain Adaptation and Caffeine Dependence

When caffeine blocks adenosine receptors day after day, the brain responds by creating more of those receptors. This process, known as upregulation, allows adenosine to continue exerting its effects despite caffeine’s presence. Over time, this adaptation reduces caffeine’s stimulating impact, leading people to consume larger amounts to achieve the same level of alertness. What begins as a single cup of coffee may gradually become several cups, energy drinks, or high-dose supplements.

This neural adaptation is the foundation of caffeine dependence. Dependence does not necessarily imply addiction in the clinical sense, but it does mean that the brain has adjusted its normal functioning to accommodate a constant presence of caffeine. In this adapted state, the brain expects caffeine to be there. When it suddenly disappears, the balance is disrupted in the opposite direction.

Without caffeine blocking them, the increased number of adenosine receptors become fully available. Adenosine can now bind in greater amounts than before, producing an exaggerated signal of fatigue and sedation. This sudden shift explains why withdrawal symptoms can feel intense and overwhelming, even in people who consumed what they considered moderate amounts of caffeine.

The First Hours Without Caffeine: A Sudden Neurochemical Shift

Within twelve to twenty-four hours after the last dose of caffeine, the brain begins to register its absence. Adenosine signaling increases sharply as the previously blocked receptors become active. This surge in adenosine activity slows neuronal firing across multiple brain regions, particularly those involved in alertness and executive function.

One of the earliest and most common symptoms during this phase is a headache. From a neurological standpoint, this headache is linked to changes in cerebral blood flow. Caffeine normally constricts blood vessels in the brain. When caffeine is removed, these blood vessels dilate, increasing blood flow and pressure within the skull. This vascular expansion stimulates pain-sensitive structures, producing the characteristic throbbing headache associated with caffeine withdrawal.

At the same time, the brain’s reward circuitry experiences a drop in dopamine signaling. Caffeine enhances dopamine transmission indirectly, and its absence can lead to a temporary reduction in motivation and mood. This is why people often feel mentally dull, emotionally flat, or unusually irritable during the first day without caffeine.

Fatigue, Brain Fog, and Cognitive Slowing

As withdrawal progresses into the first few days, fatigue becomes more pronounced. The brain, now flooded with adenosine signals, shifts toward a state that prioritizes rest and recovery. Reaction times slow, attention becomes harder to sustain, and working memory may feel impaired. Tasks that once felt simple can require significantly more mental effort.

This cognitive slowing is not a sign of permanent damage or declining intelligence. Rather, it reflects the brain’s temporary recalibration. Neural networks that had been artificially stimulated by caffeine must now operate without that external boost. Until adenosine receptor numbers return to baseline, the brain remains biased toward sleepiness and low arousal.

Emotionally, this phase can be challenging. Increased irritability, low mood, and even mild depressive symptoms are common. From a neurochemical perspective, these emotional shifts are linked to changes in dopamine and serotonin balance. Caffeine’s removal reduces stimulation of reward pathways, and the brain takes time to restore equilibrium. During this period, people may feel less pleasure from activities they normally enjoy, a phenomenon known as anhedonia.

Sleep Changes and the Brain’s Recovery Process

One of the most profound effects of quitting caffeine occurs during sleep. Caffeine interferes with sleep by blocking adenosine and delaying the brain’s natural transition into deeper sleep stages. When caffeine is removed, adenosine signaling rebounds, often leading to increased sleepiness and longer sleep duration, especially in the first week.

At first, this rebound sleep can feel excessive. People may sleep longer than usual and still wake up feeling groggy. This reflects the brain’s effort to repay a sleep debt that accumulated during caffeine use. Over time, however, sleep architecture begins to normalize. Deep sleep, also known as slow-wave sleep, becomes more robust, supporting memory consolidation and neural repair.

Rapid eye movement sleep, which is essential for emotional processing and learning, may also improve. Many people report more vivid dreams after quitting caffeine, a sign that REM sleep is becoming less fragmented. These changes indicate that the brain is restoring natural sleep-wake regulation rather than relying on chemical stimulation to maintain alertness.

Anxiety, Stress, and the Calming of Neural Circuits

Caffeine stimulates the central nervous system and activates stress-related pathways, including the release of cortisol and adrenaline. In sensitive individuals, this stimulation can contribute to anxiety, restlessness, and a persistent sense of tension. When caffeine is removed, these stress pathways gradually quiet down.

During the early stages of withdrawal, anxiety can paradoxically increase. This short-term rise is linked to neurochemical instability and discomfort rather than true psychological distress. As the brain adapts, however, baseline anxiety levels often decrease. Neural circuits involved in threat detection and emotional regulation become less reactive without constant stimulation.

Over the long term, quitting caffeine may enhance emotional resilience. The brain becomes better at distinguishing genuine stressors from artificial arousal. This calmer neural environment supports clearer thinking, improved emotional control, and a more stable mood.

Blood Flow, Energy Metabolism, and Mental Clarity

Caffeine affects not only neurotransmitters but also cerebral metabolism. By increasing neuronal firing and blood vessel constriction, caffeine alters how energy is used in the brain. When caffeine is withdrawn, cerebral blood flow increases, delivering more oxygen and glucose to brain tissue.

Although this increased blood flow contributes to headaches initially, it may also support long-term brain health. Enhanced circulation improves nutrient delivery and waste removal, processes essential for maintaining neural function. As withdrawal symptoms subside, many people report a sense of mental clarity that feels different from caffeine-induced alertness. This clarity is often described as calmer, more sustainable, and less jittery.

The brain’s energy systems also adapt. Without relying on caffeine to override fatigue signals, the brain becomes more attuned to natural rhythms of energy and rest. This recalibration supports more consistent alertness throughout the day rather than sharp peaks followed by crashes.

The Timeline of Brain Recovery

The duration of caffeine withdrawal varies depending on factors such as daily intake, duration of use, individual sensitivity, and genetics. For most people, acute withdrawal symptoms peak within the first two to three days and gradually diminish over the following week. Headaches and fatigue often resolve first, while mood and motivation may take slightly longer to normalize.

At the receptor level, adenosine receptor numbers gradually decrease as the brain recognizes that caffeine is no longer present. This process can take several weeks, but noticeable improvements in mental and emotional stability often occur much sooner. By the end of one month, most individuals experience a new baseline of energy and focus that no longer depends on caffeine.

Importantly, the brain does not lose its capacity for alertness without caffeine. Instead, it relearns how to regulate wakefulness using internal signals rather than external stimulation. This transition can feel uncomfortable, but it reflects a return to physiological balance rather than a loss of function.

Psychological Identity and the Habit Loop

Beyond neurochemistry, quitting caffeine also affects the brain’s habit-forming systems. Caffeine consumption is often tied to routines, social interactions, and emotional comfort. The brain associates caffeine with productivity, warmth, and reward, reinforcing its use through learned behavior.

When caffeine is removed, these habit loops are disrupted. The brain must form new associations to replace the old ones. This psychological adjustment can be as challenging as the physical withdrawal. Morning rituals may feel incomplete, and the absence of a familiar stimulant can create a sense of loss.

Over time, however, new habits emerge. The brain’s reward system adapts, finding satisfaction in activities that were previously overshadowed by caffeine’s effects. This process highlights that withdrawal is not merely a chemical event but a holistic transformation involving behavior, emotion, and cognition.

Long-Term Changes and Cognitive Performance

A common concern among people considering quitting caffeine is whether their cognitive performance will suffer permanently. Scientific evidence does not support this fear. While caffeine can enhance alertness in the short term, it does not improve baseline intelligence or long-term cognitive ability.

After withdrawal, cognitive performance typically returns to normal levels and, in some cases, improves. Tasks that require sustained attention may feel more natural without reliance on stimulants. Memory function benefits from improved sleep quality, and emotional regulation supports clearer decision-making.

The brain’s plasticity ensures that neural networks adapt to new conditions. Once caffeine is removed, the brain optimizes its functioning within a stimulant-free environment. This adaptability is a testament to the brain’s resilience rather than a vulnerability.

The Emotional Meaning of Quitting Caffeine

For many people, quitting caffeine is not just a biological experiment but an emotional journey. It can reveal how deeply modern life encourages constant stimulation and how difficult it can be to tolerate natural fluctuations in energy and mood. Withdrawal discomfort often exposes the extent to which caffeine masked fatigue, stress, or insufficient rest.

As the brain recovers, many individuals report a renewed connection to their internal signals. Hunger, tiredness, and focus become clearer cues rather than inconveniences to be overridden. This awareness can foster healthier relationships with sleep, work, and self-care.

Emotionally, quitting caffeine can feel like reclaiming autonomy over one’s mental state. Instead of relying on an external substance to function, the brain learns to regulate itself. This shift often brings a sense of calm confidence and stability.

What Quitting Caffeine Reveals About the Brain

The brain’s response to caffeine withdrawal offers a powerful lesson about neuroplasticity and balance. It demonstrates how quickly neural systems adapt to repeated chemical influences and how equally capable they are of returning to equilibrium when those influences are removed.

Withdrawal symptoms are not signs of weakness or failure. They are predictable outcomes of biological adaptation. Understanding this reframes discomfort as evidence of the brain’s remarkable ability to adjust, protect itself, and seek balance.

Caffeine withdrawal also highlights the delicate interplay between culture and biology. In a society that values constant productivity, caffeine becomes a tool for extending wakefulness beyond natural limits. When the brain resists this extension, withdrawal forces a reckoning with human physiological needs.

A Brain Without Caffeine: A New Equilibrium

Eventually, the brain reaches a new steady state without caffeine. Adenosine signaling stabilizes, receptor numbers normalize, and neurotransmitter systems regain balance. Energy levels become more consistent, sleep improves, and emotional reactivity often decreases.

This new equilibrium does not imply permanent fatigue or diminished drive. Instead, it reflects a brain operating in alignment with its natural rhythms. Alertness arises from rest, nutrition, and circadian regulation rather than pharmacological intervention.

For some, this state feels liberating. For others, it requires ongoing adjustment and lifestyle changes to support healthy energy levels. In either case, the brain demonstrates its capacity to function effectively without caffeine once given the opportunity to adapt.

Conclusion: Withdrawal as a Window Into Brain Function

Quitting caffeine offers a rare window into the brain’s inner workings. It reveals how a common substance reshapes neural signaling, how dependence forms through adaptation, and how recovery unfolds through plasticity. The discomfort of withdrawal is not an anomaly but a reflection of fundamental neurobiological principles.

When caffeine leaves the system, the brain does not collapse. It recalibrates. Through headaches, fatigue, emotional shifts, and eventual clarity, the brain navigates a return to balance. This journey underscores the resilience of neural systems and their ability to thrive without constant stimulation.

Understanding what happens to the brain when caffeine is removed transforms withdrawal from a mysterious ordeal into a meaningful process. It becomes a story of adaptation, recovery, and renewed connection to the brain’s natural intelligence.