Imagine standing still, yet feeling as if the ground beneath you is shifting. The walls may appear to spin, or the room may seem to tilt as though you are on a ship caught in rough waters. This disorienting sensation is vertigo—a condition that can transform simple daily tasks into overwhelming challenges.

Vertigo is more than just dizziness. While dizziness is a broad term describing lightheadedness or imbalance, vertigo is a distinct medical condition in which a person perceives movement where none exists. It can feel like spinning, swaying, or tumbling, often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and difficulty walking. For some, vertigo episodes last only a few seconds; for others, they can persist for hours or even days.

Understanding vertigo requires delving into the complex interactions of the inner ear, brain, and nervous system. It is both a symptom and a syndrome, pointing to underlying issues ranging from minor disturbances to serious neurological conditions. To truly grasp what vertigo is, one must explore its causes, symptoms, methods of diagnosis, and the wide spectrum of treatments that restore balance to lives disrupted by this invisible storm.

The Science of Balance: Why Vertigo Happens

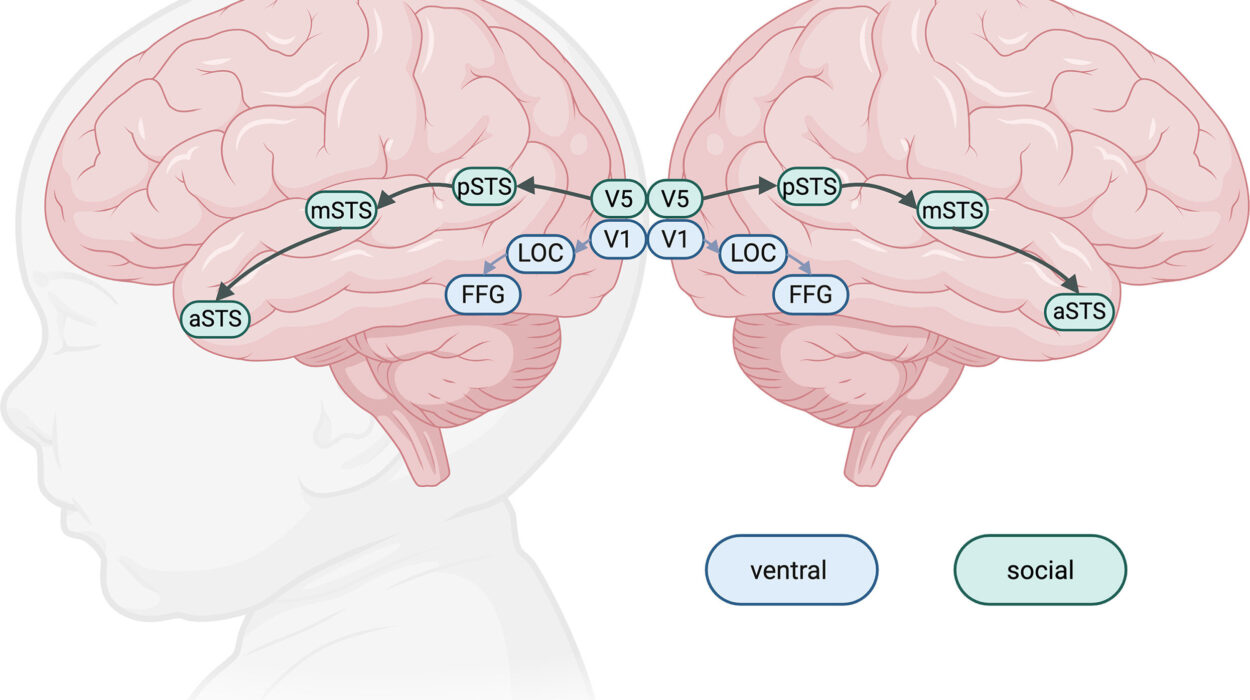

At the heart of vertigo lies the vestibular system, a sophisticated structure located within the inner ear. This system, composed of the semicircular canals, the utricle, and the saccule, works in tandem with the eyes and the brain to maintain balance and spatial orientation.

The semicircular canals detect rotational movements of the head, while the utricle and saccule detect linear movements and the pull of gravity. These structures are filled with fluid and lined with tiny sensory hair cells that send signals to the brain about movement and position. When the vestibular system malfunctions—whether due to displacement of tiny calcium crystals, infection, inflammation, or neurological issues—the result is vertigo.

Causes of Vertigo

Vertigo is not a disease in itself but a symptom of various conditions. Understanding its causes is essential to providing effective treatment.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

BPPV is the most common cause of vertigo. It occurs when small calcium carbonate crystals, called otoconia, become dislodged from the utricle and migrate into one of the semicircular canals. When the head changes position—such as lying down, turning over in bed, or looking upward—the crystals shift, sending false signals to the brain that the body is spinning.

BPPV episodes are usually brief, lasting seconds to minutes, but they can be frightening and disruptive. The exact cause of crystal displacement is not always clear, though aging, head injuries, and inner ear infections can increase risk.

Ménière’s Disease

Ménière’s disease is a chronic inner ear disorder characterized by episodes of vertigo, hearing loss, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), and a feeling of fullness in the ear. It is thought to result from abnormal fluid buildup in the inner ear, though the exact cause is unknown. Vertigo attacks in Ménière’s disease can last for hours, leaving sufferers exhausted and debilitated.

Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

Both conditions involve inflammation of the inner ear or the vestibular nerve, usually due to viral infections. Vestibular neuritis primarily affects balance, while labyrinthitis also impacts hearing. Symptoms often come on suddenly and can be severe, lasting days before gradually improving.

Migrainous Vertigo (Vestibular Migraine)

Some individuals experience vertigo as part of a migraine disorder. Vestibular migraines can cause spinning sensations, imbalance, nausea, and sensitivity to light and sound, with or without the classic migraine headache. The connection between migraines and vertigo is not fully understood, but it highlights the intricate relationship between the brain and vestibular system.

Head or Neck Trauma

Injuries to the head or neck can damage the vestibular system or disrupt its communication with the brain, leading to vertigo. Whiplash injuries and concussions are common triggers.

Neurological Conditions

Though less common, vertigo can signal serious conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or brain tumors. In these cases, vertigo is often accompanied by other neurological symptoms such as double vision, difficulty speaking, weakness, or loss of coordination.

Other Causes

- Medications: Certain drugs, particularly those toxic to the inner ear (ototoxic drugs), can cause vertigo.

- Otosclerosis: Abnormal bone growth in the middle ear can affect hearing and balance.

- Dehydration and Low Blood Pressure: These can cause dizziness and occasionally vertigo-like sensations.

Symptoms of Vertigo

The hallmark of vertigo is the sensation of movement, often described as spinning or swaying. Yet, vertigo rarely comes alone—it typically brings a cluster of symptoms that vary depending on the cause and severity.

Common symptoms include:

- Spinning, tilting, swaying, or rocking sensations

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of balance and unsteadiness when walking

- Nystagmus (involuntary, rapid eye movements)

- Headaches or migraines

- Sweating and anxiety during episodes

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus) or hearing loss (in cases like Ménière’s disease)

These symptoms can be brief and mild, or intense and disabling. The unpredictability of vertigo often adds to the distress it causes. People may fear leaving home, driving, or engaging in activities, worried that an attack will suddenly strike.

Diagnosis of Vertigo

Because vertigo can arise from multiple causes, diagnosis often involves a combination of detailed history, physical examination, and specialized tests.

Medical History and Symptom Description

Doctors first ask patients to describe their symptoms—when they began, how long they last, what triggers them, and whether hearing loss or other neurological issues are present. This narrative helps narrow down the likely cause.

Physical Examination

The physical exam may include balance and coordination tests. One of the most well-known diagnostic maneuvers is the Dix-Hallpike test, used to identify BPPV. In this test, the patient is quickly moved from a sitting to a lying position with the head tilted, while the doctor observes eye movements (nystagmus) that indicate crystal displacement in the inner ear.

Hearing Tests

Audiometry can detect hearing loss associated with Ménière’s disease or labyrinthitis.

Imaging

MRI or CT scans may be ordered if neurological causes like stroke or tumors are suspected.

Vestibular Function Tests

Specialized tests, such as electronystagmography (ENG), videonystagmography (VNG), and vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP), measure eye and muscle responses to assess vestibular system function.

Treatment of Vertigo

Treatment depends on the underlying cause of vertigo. Some cases resolve spontaneously, while others require targeted therapy.

Treating BPPV

The most effective treatment for BPPV is repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver or Semont maneuver. These involve a series of head and body movements that guide the displaced crystals out of the semicircular canal and back into the utricle, where they no longer cause vertigo. These maneuvers often provide immediate or rapid relief.

Treating Ménière’s Disease

There is no cure for Ménière’s disease, but treatments can help manage symptoms. These may include:

- Dietary changes, such as reducing salt intake to limit fluid buildup

- Diuretics (water pills) to decrease inner ear pressure

- Medications to control vertigo attacks and nausea

- Hearing aids for progressive hearing loss

- In severe cases, surgery to reduce inner ear pressure or selectively disable the vestibular system

Treating Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis

Corticosteroids may reduce inflammation in the acute phase. Antiviral medications are sometimes used if a viral cause is suspected. Over time, the brain often adapts to vestibular damage through a process called compensation, aided by physical therapy.

Treating Vestibular Migraines

Management focuses on controlling migraine triggers through diet, stress management, and medications such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or anticonvulsants.

General Medications

For short-term relief of acute vertigo episodes, doctors may prescribe:

- Vestibular suppressants (meclizine, diazepam)

- Antiemetics (ondansetron, promethazine) for nausea

These medications are generally used short-term, as prolonged use can hinder the brain’s natural compensatory mechanisms.

Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT)

VRT is a specialized form of physical therapy that trains the brain to adapt to vestibular dysfunction. Exercises may include eye, head, and body movements designed to improve balance, coordination, and gaze stability. VRT is highly effective for chronic vertigo and imbalance.

Lifestyle Modifications

- Staying hydrated and avoiding excessive caffeine and alcohol

- Reducing stress, which can worsen symptoms

- Sleeping well and maintaining a consistent schedule

- Avoiding sudden head movements in conditions like BPPV

Surgery

In rare cases where vertigo is severe and unresponsive to other treatments, surgical options may be considered. These range from procedures to decompress the inner ear to selectively disabling the vestibular nerve. Surgery is typically reserved for debilitating cases such as advanced Ménière’s disease.

Living with Vertigo

Beyond the medical aspects, living with vertigo often means confronting fear, frustration, and isolation. Vertigo can erode confidence—something as simple as walking down the street can feel daunting. Yet, with proper diagnosis and treatment, most people can manage their symptoms and reclaim a sense of control.

Support from family, friends, and healthcare providers is crucial. Patient education, counseling, and support groups can reduce anxiety and empower individuals to face vertigo with resilience.

When Vertigo Signals Something Serious

While most vertigo cases are benign, certain red flags require urgent medical attention. These include:

- Sudden, severe vertigo with inability to walk

- Vertigo accompanied by double vision, slurred speech, weakness, or numbness

- Vertigo following head injury

- Progressive hearing loss or severe headache

Such symptoms may indicate stroke, brain hemorrhage, or other neurological emergencies. Immediate evaluation can be lifesaving.

The Future of Vertigo Treatment

Advances in medical science continue to expand options for those with vertigo. Research into genetic factors, new medications, and more precise diagnostic tools promises earlier detection and more personalized treatments. Virtual reality technologies are being explored for vestibular rehabilitation, offering immersive exercises to retrain the brain.

As understanding of the vestibular system deepens, hope grows for even more effective ways to restore balance—both physically and emotionally—for those whose lives are disrupted by vertigo.

Conclusion: Restoring Balance to Life

Vertigo is more than a fleeting sense of dizziness; it is a window into the delicate and complex systems that keep us upright and oriented in the world. Whether caused by tiny dislodged crystals in the inner ear or more serious neurological conditions, vertigo challenges both the body and the spirit.

Yet, it is not an insurmountable condition. Through accurate diagnosis, targeted treatments, and supportive care, people can find relief, regain confidence, and restore balance in every sense of the word. Health, after all, is not merely the absence of spinning—it is the ability to stand steady, move forward, and embrace life with clarity and resilience.