To understand the difference between benign and malignant tumors, we must first clarify what a tumor actually is. The word “tumor” is often used synonymously with “cancer,” but that isn’t entirely accurate. A tumor, in the simplest terms, is an abnormal mass of tissue that results when cells divide more than they should or do not die when they should. This can happen almost anywhere in the body—within organs, bones, soft tissues, or even the brain.

Normally, our cells grow and divide in a highly controlled, orderly process. Old or damaged cells die through a natural process called apoptosis, and new cells take their place. But sometimes this regulatory system goes awry. A cell might mutate, ignore the usual stop signs, and start multiplying uncontrollably. When this happens, a lump of tissue can form—a tumor.

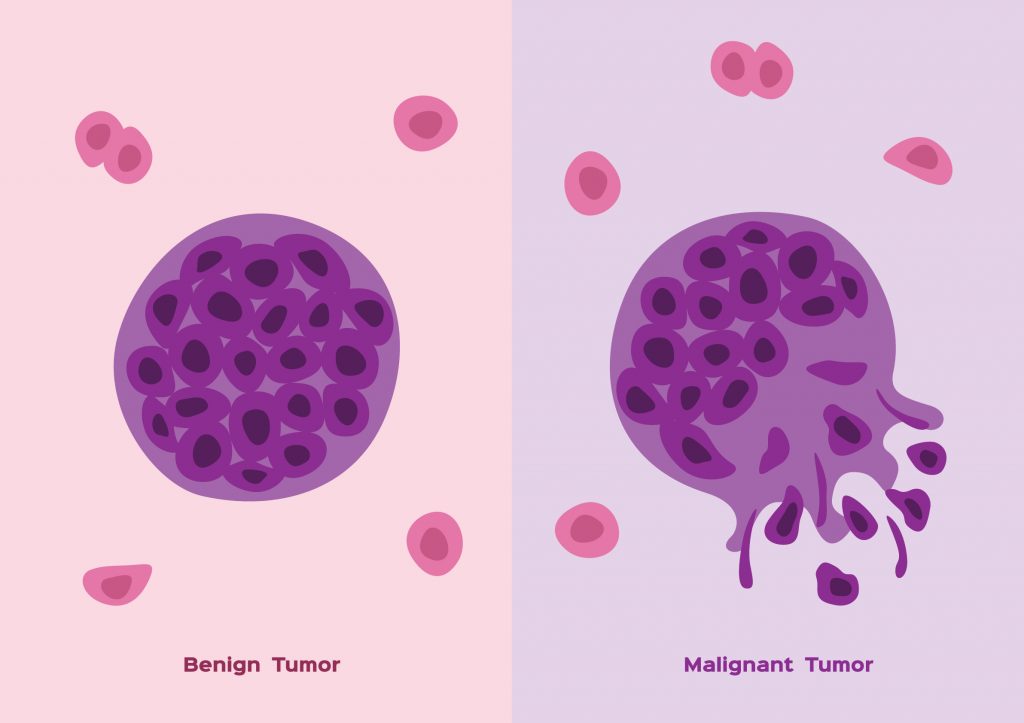

However, not all tumors are created equal. Some remain confined, harmless, and easy to treat. Others grow aggressively, invade nearby tissues, and even spread to distant parts of the body. These two classes of tumors are referred to as benign and malignant. While they may start from similar biological roots, the journey each takes and the consequences they bring are profoundly different.

Benign Tumors Stay in Their Lane

Benign tumors are the non-cancerous kind. They may sound frightening—after all, the word “tumor” does carry an ominous tone—but benign tumors are generally considered less dangerous and more predictable. The most important trait of a benign tumor is that it does not invade nearby tissues or metastasize to other parts of the body. In other words, it stays put.

Benign tumors tend to grow slowly. They often develop a clear boundary or capsule, which makes them easier to surgically remove. Their cells, when viewed under a microscope, often look quite similar to normal cells, although they might be more numerous and slightly enlarged. Importantly, they maintain a level of structural and functional order that malignant tumors do not.

These tumors can occur in many forms—fibromas, lipomas, adenomas, hemangiomas. A lipoma, for instance, is a benign tumor composed of fat cells. It might appear as a soft, rubbery lump under the skin and rarely causes problems beyond cosmetic annoyance. An adenoma might arise in glandular tissue, such as the thyroid or adrenal glands, and in some cases may produce hormones that affect body function. Still, with proper monitoring and management, most benign tumors pose no life-threatening danger.

That being said, benign doesn’t always mean harmless. Depending on their location, even non-cancerous growths can cause significant problems. A benign brain tumor, for example, may press against sensitive areas and interfere with neurological function. Benign tumors can also cause complications by secreting hormones or obstructing blood flow or organ function. In rare cases, some benign tumors have the potential to become malignant over time, although this transition is relatively uncommon.

Malignant Tumors Break the Rules

Malignant tumors are cancerous, and they play by an entirely different set of rules. Where benign tumors are well-behaved, malignant tumors are anarchists. They grow uncontrollably, invade nearby tissues, and, most ominously, spread to distant parts of the body in a process called metastasis. This makes them significantly more dangerous and challenging to treat.

At the cellular level, malignant tumors are far more chaotic. The cells often appear abnormal under a microscope. Their size, shape, and organization can vary widely, a phenomenon called pleomorphism. They may have large, misshapen nuclei and divide rapidly, indicating a loss of the typical regulatory mechanisms that keep cell growth in check.

One of the defining features of malignant tumors is their ability to infiltrate. Unlike benign tumors, which typically remain contained, malignant tumors invade surrounding tissues. They can cross into blood vessels or lymphatic channels and hitch a ride to distant organs. A breast cancer cell, for instance, might travel to the bones, lungs, or liver and begin forming new tumors there. These distant colonies of cancer cells are known as metastases, and they significantly complicate treatment and reduce survival rates.

Malignant tumors also have a remarkable ability to evade the immune system. Normally, the body has a sophisticated defense network designed to detect and destroy abnormal cells. But cancer cells can manipulate this system, disguising themselves or actively suppressing immune responses. Some even create their own blood supply by stimulating angiogenesis, drawing in nutrients to fuel their relentless growth.

The types of malignant tumors are numerous and varied. Carcinomas arise from epithelial cells and include cancers of the skin, lungs, and colon. Sarcomas develop from connective tissues like bone or muscle. Leukemias and lymphomas affect blood and immune system cells. Each has its own patterns of behavior, treatment challenges, and prognosis, but they all share the core characteristics of malignancy: unregulated growth, invasiveness, and the capacity for metastasis.

How Tumors Get Their Names and Behavior

The naming of tumors provides critical information about their origin and behavior. The suffix “-oma” generally denotes a benign tumor, as in lipoma or adenoma. However, there are important exceptions. Melanoma, lymphoma, and glioblastoma are all malignant despite their “-oma” endings. The context and prefix matter significantly.

Benign tumors usually include information about the tissue of origin. For example, a “chondroma” is a benign tumor of cartilage. In contrast, the malignant version would be called “chondrosarcoma.” The suffix “-sarcoma” or “-carcinoma” signals malignancy and typically prompts urgent medical attention.

In the clinical setting, behavior often trumps name. A small, benign tumor that causes pain, compresses an artery, or obstructs the bowel may be a greater immediate concern than a tiny, slow-growing carcinoma. That’s why diagnosis involves more than a label—it includes imaging, biopsy, staging, and sometimes molecular profiling to understand how aggressive the tumor is likely to be.

What Causes a Tumor to Be Benign or Malignant

The distinction between benign and malignant tumors begins at the molecular level. DNA mutations are the root of most tumors, but the type, number, and effect of these mutations determine the tumor’s behavior. In a benign tumor, mutations may cause excessive growth but leave mechanisms of order and containment intact. In malignant tumors, mutations tend to disable these control systems altogether.

Malignancy usually arises through a multi-step process called carcinogenesis. First, an initial mutation gives a cell a growth advantage. Additional mutations may enable the cell to ignore death signals, recruit blood vessels, and break through tissue barriers. Eventually, the accumulation of these genetic changes leads to a fully malignant phenotype.

Environmental factors such as radiation, tobacco smoke, alcohol, infectious agents, and industrial chemicals can all contribute to this process. Some individuals inherit genetic mutations that predispose them to certain cancers, such as mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. But while malignancy is a genetic disease, it’s also influenced by the cellular environment and the immune system.

The tipping point between benign and malignant isn’t always easy to define. Some tumors exist in a gray zone—borderline or “potentially malignant” tumors that may remain stable for years or suddenly become aggressive. That’s why early detection, careful monitoring, and biopsies are crucial in guiding treatment decisions.

The Role of the Immune System in Tumor Behavior

Our immune system plays a double-edged role in the development of tumors. On the one hand, immune cells are constantly patrolling the body for signs of abnormal growth. Specialized cells such as natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes can recognize and destroy mutated or damaged cells before they develop into full-fledged tumors.

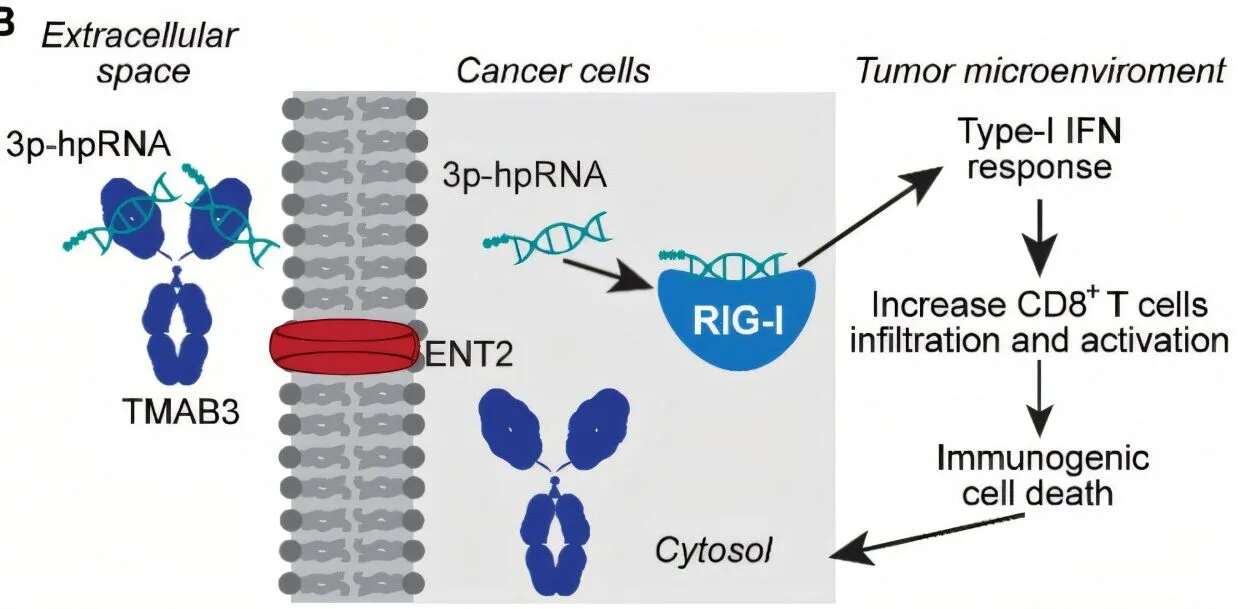

On the other hand, malignant tumors often evolve ways to suppress or evade this immune surveillance. Some cancers produce immune checkpoint proteins that turn off attacking immune cells. Others release anti-inflammatory signals that trick the immune system into ignoring them.

In benign tumors, the immune system generally maintains control. These tumors are often visible to the immune system but are not threatening enough to provoke a strong response. In malignancy, the immune system either fails to recognize the threat or is actively suppressed by the tumor itself.

This interplay has led to the development of immunotherapies—treatments that reawaken the immune system’s ability to fight cancer. Drugs called checkpoint inhibitors block the “off switches” used by cancer cells, allowing immune cells to attack again. These therapies have revolutionized the treatment of some malignant cancers, offering hope where chemotherapy and radiation have failed.

How Doctors Diagnose and Differentiate Tumors

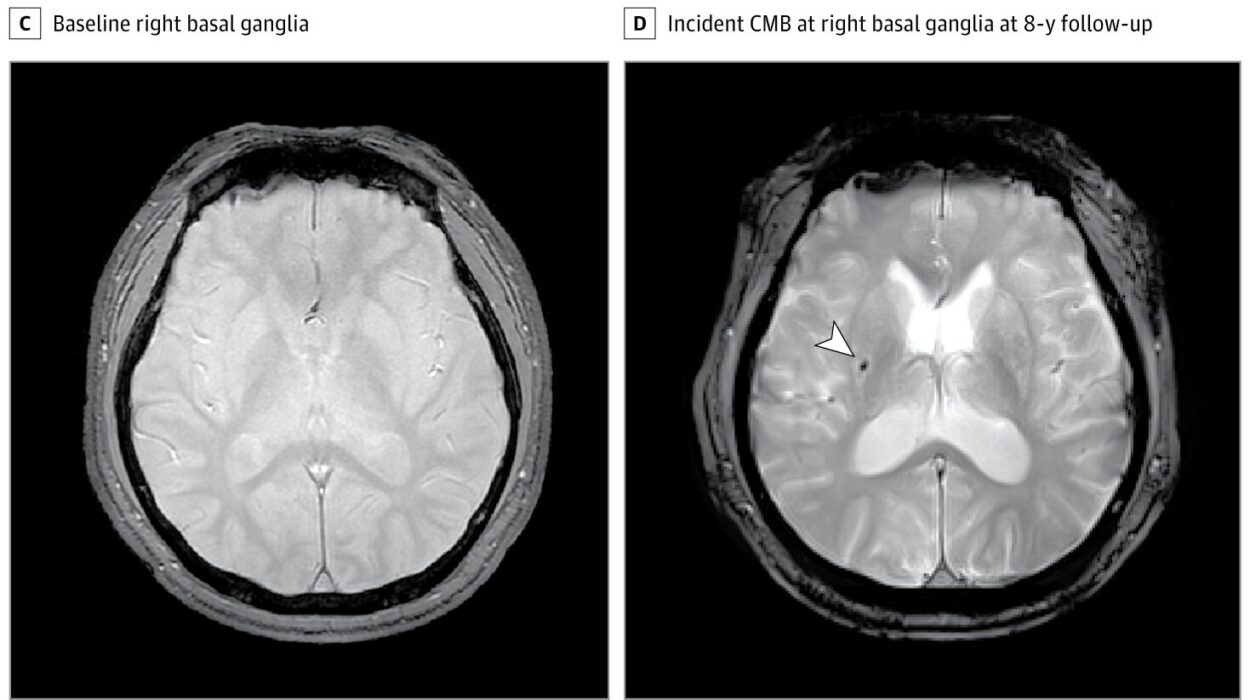

Diagnosing whether a tumor is benign or malignant involves a combination of imaging, biopsy, and laboratory analysis. Imaging techniques such as MRI, CT scans, and ultrasounds can reveal the size, shape, and location of a mass. Certain features—such as irregular borders, rapid growth, or invasion into nearby tissues—raise suspicion of malignancy.

The most definitive tool is a biopsy, where a sample of the tumor is removed and examined under a microscope. Pathologists look at cellular architecture, mitotic activity, nuclear features, and other markers of abnormality. Immunohistochemistry and molecular profiling may be used to identify specific proteins or genetic mutations.

In malignant tumors, doctors also perform staging to determine how far the cancer has spread. This involves looking at the size of the primary tumor (T), involvement of nearby lymph nodes (N), and presence of metastases (M)—a system known as TNM staging. Benign tumors do not require this kind of staging because they do not metastasize.

Treatment Approaches for Benign and Malignant Tumors

Treating a benign tumor is often a matter of surgical removal, followed by observation. Many benign tumors don’t even need treatment unless they cause symptoms or discomfort. When they are removed, they often do not return.

Malignant tumors, by contrast, require a multi-pronged strategy. Treatment usually involves a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and increasingly, targeted therapies or immunotherapy. The goal is not just to remove the tumor but to kill or suppress any remaining cancer cells that might lead to recurrence or metastasis.

Because malignant tumors are more unpredictable, their treatment must be more aggressive. Even after remission, patients are often monitored for years for signs of recurrence. The treatment burden—physically, emotionally, and financially—is significantly greater than with benign tumors.

The Psychological Weight of a Diagnosis

Receiving a tumor diagnosis, even if it’s benign, can be emotionally taxing. The word “tumor” evokes fear, uncertainty, and a confrontation with mortality. Patients often undergo a rollercoaster of emotions—relief if it’s benign, devastation if it’s malignant.

Malignant cancer adds layers of complexity: decisions about treatment options, side effects, lifestyle changes, family planning, and career disruptions. Even the word “cancer” carries a social stigma and a gravity that no other diagnosis quite matches.

Support systems—family, friends, counselors, support groups—become crucial. Mental health plays a significant role in a patient’s outcome, influencing their ability to navigate treatment and maintain hope. Understanding the difference between benign and malignant tumors, and having clear communication from healthcare providers, can alleviate some of the psychological burden.

Looking to the Future of Tumor Treatment and Prevention

The boundary between benign and malignant tumors is one that science continues to explore. Advances in genomics, artificial intelligence, and biomarker research are helping doctors predict more accurately which tumors are likely to become dangerous. Personalized medicine is tailoring treatments to the genetic makeup of individual tumors, improving outcomes and reducing unnecessary interventions.

Preventive strategies—vaccination against cancer-causing viruses, anti-smoking campaigns, dietary guidelines, and genetic screening—are empowering people to reduce their risk of developing malignant tumors. New imaging tools and liquid biopsies (which detect tumor DNA in the bloodstream) are making early detection faster and less invasive.

Though benign and malignant tumors differ greatly in severity, both arise from the same fundamental question: What happens when cells refuse to follow the rules? As we decode the answers, we move closer to a future where all tumors—regardless of type—can be understood, managed, and perhaps one day, entirely prevented.