In the pantheon of human health threats, few diseases have a grip on our collective imagination like cancer. It conjures images of uncertainty, suffering, and scientific urgency. Yet while our tools for diagnosing and treating cancer have improved dramatically in recent decades, the disease itself has become more prevalent. Global cancer rates are rising, not falling. The very word “cancer” may soon outnumber heart disease in its claim on lives, especially in wealthier nations. This isn’t just a statistic—it’s a seismic shift in global health that demands explanation.

The increase is not evenly distributed. Some countries are seeing sharper rises than others. Certain types of cancer are surging, while others have plateaued. And while progress in treatment has saved millions of lives, the sheer number of new diagnoses each year keeps growing. What is driving this unsettling trend? The answer is not simple, but it is revealing—about how we live, how we age, and how society is transforming at a global scale.

The Age Effect That Comes With Progress

The most powerful force behind the rise in cancer rates is, ironically, progress itself. As nations develop economically, their citizens live longer. Infectious diseases, once the dominant causes of death, are brought under control. Sanitation improves, vaccines become widespread, and emergency medical care becomes accessible. People no longer die young from pneumonia or childbirth complications. But aging comes with a catch.

Cancer is, in many ways, a disease of aging. Cells accumulate mutations over time, and as we grow older, the likelihood that a mutation will escape the body’s defenses and form a tumor increases. In a sense, the human body is a ticking cellular clock—each year a roll of the genetic dice. Living to 80 instead of 50 gives cancer decades more opportunity to develop. This doesn’t mean aging causes cancer in itself, but rather that age gives cancer time to manifest.

Globally, the average life expectancy has risen from 52 years in 1960 to over 72 years today. That’s two extra decades of life, and with it, more opportunity for genetic damage to accumulate. In wealthy countries, more than 60 percent of all cancers occur in people over 65. As low- and middle-income countries improve healthcare and nutrition, they too inherit this age-related burden. Ironically, cancer is becoming the disease of development.

The Lifestyle Factor That Fuels Modern Living

Beyond age, the way we live has changed dramatically in the past century—and not always for the better. With industrialization has come a lifestyle that makes cancer more likely. Modern life brings convenience and connectivity, but it also fosters behaviors that increase cancer risk.

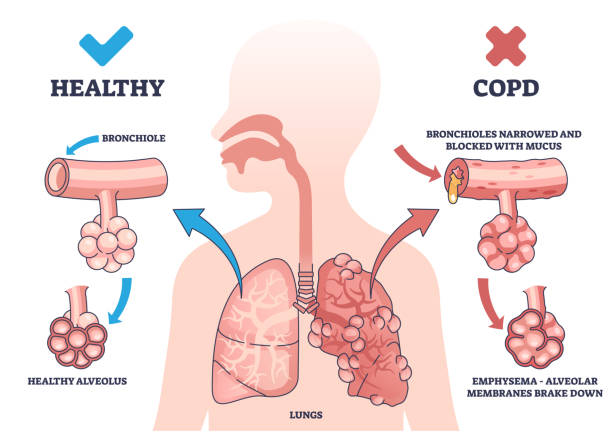

Diet is one major culprit. Processed foods high in fat, sugar, and preservatives have replaced traditional diets in many parts of the world. Obesity, once rare in most cultures, is now a global epidemic. Excess body fat leads to chronic inflammation, hormonal imbalances, and insulin resistance—all of which are fertile grounds for cancer cells to thrive. Cancers of the breast, colon, pancreas, liver, and kidney are all strongly linked to obesity.

Tobacco use remains a leading cause of preventable cancer worldwide, responsible for more than eight million deaths per year. Although smoking rates are declining in many Western countries, they are increasing in others, particularly in parts of Asia and Africa where tobacco companies now find new markets. Lung cancer, already the most deadly cancer globally, continues to claim millions of lives each year.

Alcohol consumption is another overlooked risk. Regular drinking increases the likelihood of liver, breast, esophageal, and colorectal cancers. Even moderate consumption, once thought to be safe, now shows consistent associations with cancer development in epidemiological studies.

Then there is the issue of physical inactivity. Desk jobs, long commutes, and screen-based entertainment have turned large swaths of the global population into sedentary beings. Lack of exercise contributes to obesity and dampens immune function. It’s not just about weight—movement itself is protective against cancer.

The Environmental Web That Binds Us All

Environmental exposure to carcinogens is a quieter but no less dangerous contributor to rising cancer rates. Industrialization brings with it pollution—in the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the soil in which we grow food. From exhaust fumes and asbestos to pesticides and microplastics, the modern world is awash in synthetic chemicals, many of which have been linked to cancer in both animals and humans.

In rapidly urbanizing regions, poor regulation of pollutants can lead to dangerously high exposures. Air pollution, now classified by the World Health Organization as a carcinogen, is associated with increased risks of lung cancer and even bladder cancer. In parts of China and India, where smog cloaks entire cities, this is a daily reality.

Workplace exposure also plays a role. In some industries, workers are still exposed to carcinogenic materials like benzene, formaldehyde, and silica dust. In low-income countries, safety standards are often lacking or poorly enforced, putting millions at risk every day.

Even more insidious is the long latency period of many environmental carcinogens. Someone exposed to a cancer-causing agent in their twenties may not develop symptoms until their fifties or sixties. This makes it harder to trace the cause and easier for policymakers to ignore.

The Power of Detection and Its Double-Edged Sword

One paradox of modern medicine is that its very effectiveness can skew the numbers. With better screening, cancers that once went undiagnosed are now detected early. This is particularly true for cancers like breast, prostate, thyroid, and skin cancers, where screening tools are widely used.

While early detection can save lives, it can also inflate incidence rates. A cancer that never would have progressed to harm a person in their lifetime may now be picked up on a scan and treated aggressively. This phenomenon, known as overdiagnosis, is especially prevalent in wealthier countries with access to routine medical care.

But the problem isn’t overdiagnosis alone. In many countries, screening programs are still not widely available, and cancers are often found only after they have progressed to an advanced stage. This global inequality in detection means that some regions appear to have rising rates simply because they are finally catching cases that were once missed.

Thus, statistics reflect not only disease prevalence but also our evolving capacity to identify it. In this light, rising cancer rates are partially a marker of scientific success—though one that comes with complex ethical questions about how and when we intervene.

The Viral Link That Connects Infection and Cancer

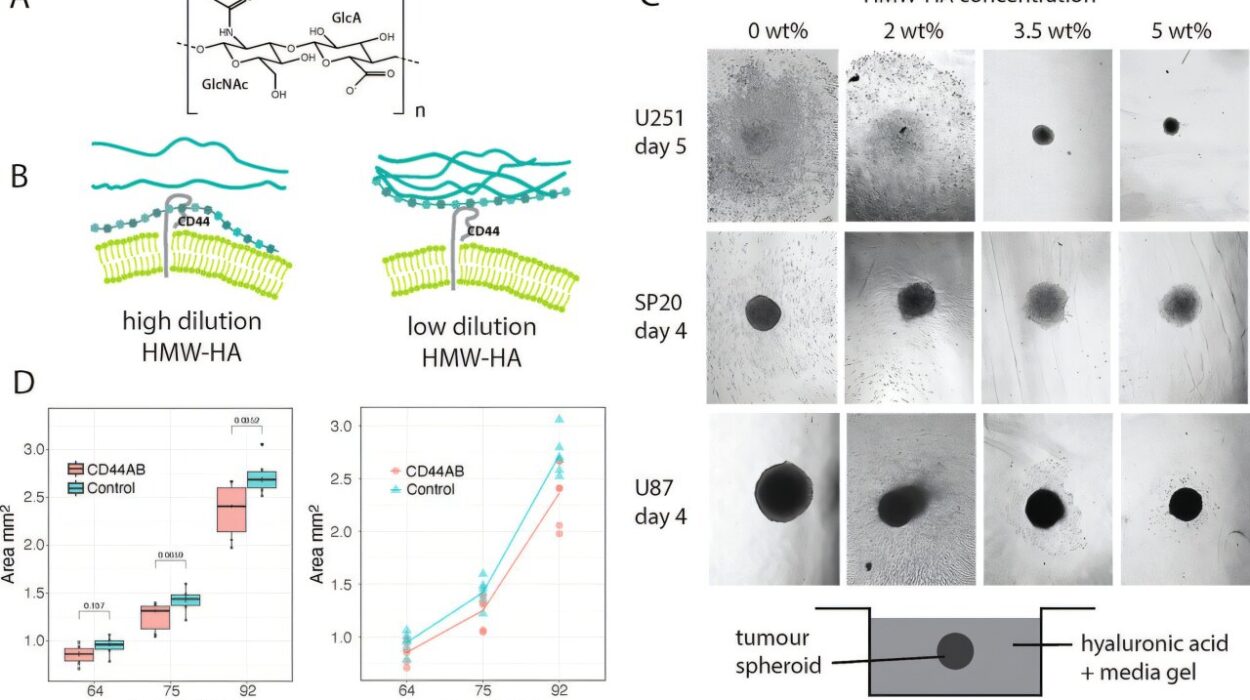

Not all cancers arise from genetics or lifestyle. A surprising proportion—around 15 percent globally—are caused by infectious agents. Viruses such as human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B and C, Epstein-Barr virus, and HIV can all set the stage for cancer development by disrupting normal cell function or weakening the immune system.

HPV is a major driver of cervical cancer, which remains one of the leading cancer killers among women in developing countries. Despite the availability of an effective vaccine, HPV continues to spread in regions where vaccination rates are low and routine Pap smears are not accessible.

Liver cancer, common in parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, is often the result of chronic hepatitis infections. Like cervical cancer, it is largely preventable through vaccination and early detection. The challenge lies in delivering these tools where they are most needed.

In parts of the world where infectious diseases are still prevalent, these cancer-related viruses add to the rising tide of diagnoses. The good news is that infection-driven cancers are among the most preventable. The bad news is that prevention remains out of reach for millions.

The Genetic Lens and the Myths It Reveals

There is a common belief that cancer is a hereditary curse—that if it “runs in the family,” it is inevitable. While certain mutations, such as those in the BRCA genes, do significantly raise cancer risk, inherited cancers make up only about 5 to 10 percent of all cases.

What’s more significant are the so-called “somatic mutations” that occur over a lifetime due to environmental exposure, lifestyle choices, or simply random chance. Every time a cell divides, there’s a small risk that it will make a mistake. Most of these are harmless or quickly repaired. But some slip through.

This randomness, sometimes called “bad luck,” plays a bigger role than previously appreciated. In this sense, cancer is not solely the fault of genes or behavior. It is the byproduct of biology itself—a natural risk that grows with each heartbeat.

However, understanding one’s genetic makeup can still be incredibly useful. Precision medicine is beginning to offer targeted therapies based on individual tumor genetics, and genetic counseling can help identify people at high risk who may benefit from enhanced screening.

The Economic Divide That Shapes Cancer’s Toll

Cancer does not strike equally. Wealth, geography, and education dramatically affect who gets cancer, who survives it, and who is left behind. In high-income countries, the most common cancers are often linked to lifestyle—colon, breast, prostate, and lung. These are increasingly detected early and treated with cutting-edge therapies.

In lower-income nations, cancer often appears later, more aggressively, and with fewer options for care. Cervical and liver cancers, which are preventable, continue to claim millions of lives for want of vaccines and screening infrastructure. Chemotherapy and radiation remain out of reach for many, and palliative care is often nonexistent.

This global cancer divide is a form of medical injustice. A child with leukemia in Europe has an 80 percent chance of survival. In sub-Saharan Africa, the same child may never be diagnosed, much less treated. Bridging this divide requires more than technology—it demands political will, global cooperation, and a commitment to health equity.

The Shadow of Survivorship and Long-Term Risk

Even as survival improves, the cancer story doesn’t end with remission. Millions of people around the world are now living with the long-term effects of cancer treatment—chronic fatigue, heart damage, secondary cancers, and psychological trauma. Survivorship is a new frontier in cancer care, and it is reshaping what it means to “beat” cancer.

As people live longer with and after cancer, the total number of individuals affected by the disease increases. This, too, drives up cancer statistics—not because more people are dying, but because more people are living with cancer as a chronic condition.

At the same time, emerging research suggests that some cancer treatments themselves may increase the risk of future cancers. Radiation, for example, can damage nearby healthy cells. Chemotherapy, while life-saving, can leave lingering cellular scars.

This complex legacy of treatment means that cancer rates will continue to rise—not only from new cases but from the long tail of survivorship and secondary disease.

The Global Future and the Call to Act

The rise in global cancer rates is not a mystery—it is a mirror. It reflects our longevity, our habits, our environment, and our economic structures. It is both a triumph of modern life and a sobering reminder of its costs.

What can be done? A great deal. Prevention remains the most powerful tool. Reducing tobacco and alcohol use, improving diets, encouraging physical activity, and promoting vaccines can significantly cut global cancer incidence. Early detection programs can save lives and reduce the cost of treatment. Equitable access to care can bridge the survival gap between rich and poor nations.

Technology is advancing rapidly. Artificial intelligence is helping radiologists spot tumors earlier. Gene sequencing is enabling personalized treatment plans. Immunotherapy is unlocking the body’s own defenses to fight cancer. But technology alone is not enough.

What we need is a global strategy—one that combines science with social justice, innovation with infrastructure, and research with reach. Cancer is rising not because we are losing, but because we are living longer, more complex lives. If we act wisely, that trend can be met with strength rather than despair.

In the end, understanding why cancer is rising is not about fear. It’s about clarity. With clarity comes action, and with action, hope.