In a groundbreaking study that could redefine how we think about cannabis and mental health, researchers from Canada have uncovered striking new evidence connecting long-term cannabis use with a key biological marker of psychosis. Published in JAMA Psychiatry, this study doesn’t just hint at a connection—it draws a straight neurological line between cannabis use disorder and elevated dopamine levels in a critical part of the brain associated with psychosis.

Led by scientists at the London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute (LHSCRI) and Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry in London, Ontario, the research uses cutting-edge brain imaging to reveal what excessive cannabis use may be doing under the hood of the human mind. For the first time, researchers have visually mapped dopamine accumulation in a brain region long linked with the onset of psychosis, offering tangible proof of what clinicians have suspected for years.

A Deeper Look: Dopamine, Cannabis, and the Brain

To understand the significance of this discovery, we first need to appreciate the role of dopamine, a powerful neurotransmitter that plays a starring role in mood, motivation, reward, and cognitive function. In the right amounts, dopamine is essential. But too much of it—particularly in specific brain circuits—can spell trouble.

“Excess levels of dopamine can disrupt normal brain processes and may increase the risk of psychosis, particularly in individuals who are already vulnerable,” explained study co-author Betsy Schaefer, coordinator at the Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychosis (PEPP) at LHSC.

While previous studies had linked cannabis use to a greater likelihood of psychotic episodes—particularly among adolescents—this research is the first to pinpoint a measurable change in the brain’s neurochemistry as the biological smoking gun.

“We now have evidence that shows a straight line linking cannabis with dopamine and psychosis that has never been shown before,” said Dr. Lena Palaniyappan, senior author of the study and a professor at McGill University. “It’s crucial that clinicians, patients, and families work together to break this line.”

Scanning the Brain’s Black Boxes

To conduct the study, researchers enrolled 61 participants between the ages of 18 and 35. The group included individuals with and without cannabis use disorder—a clinical diagnosis that refers to persistent, problematic cannabis use—and a subset of participants who had also been diagnosed with first-episode schizophrenia, a condition characterized by the onset of psychotic symptoms.

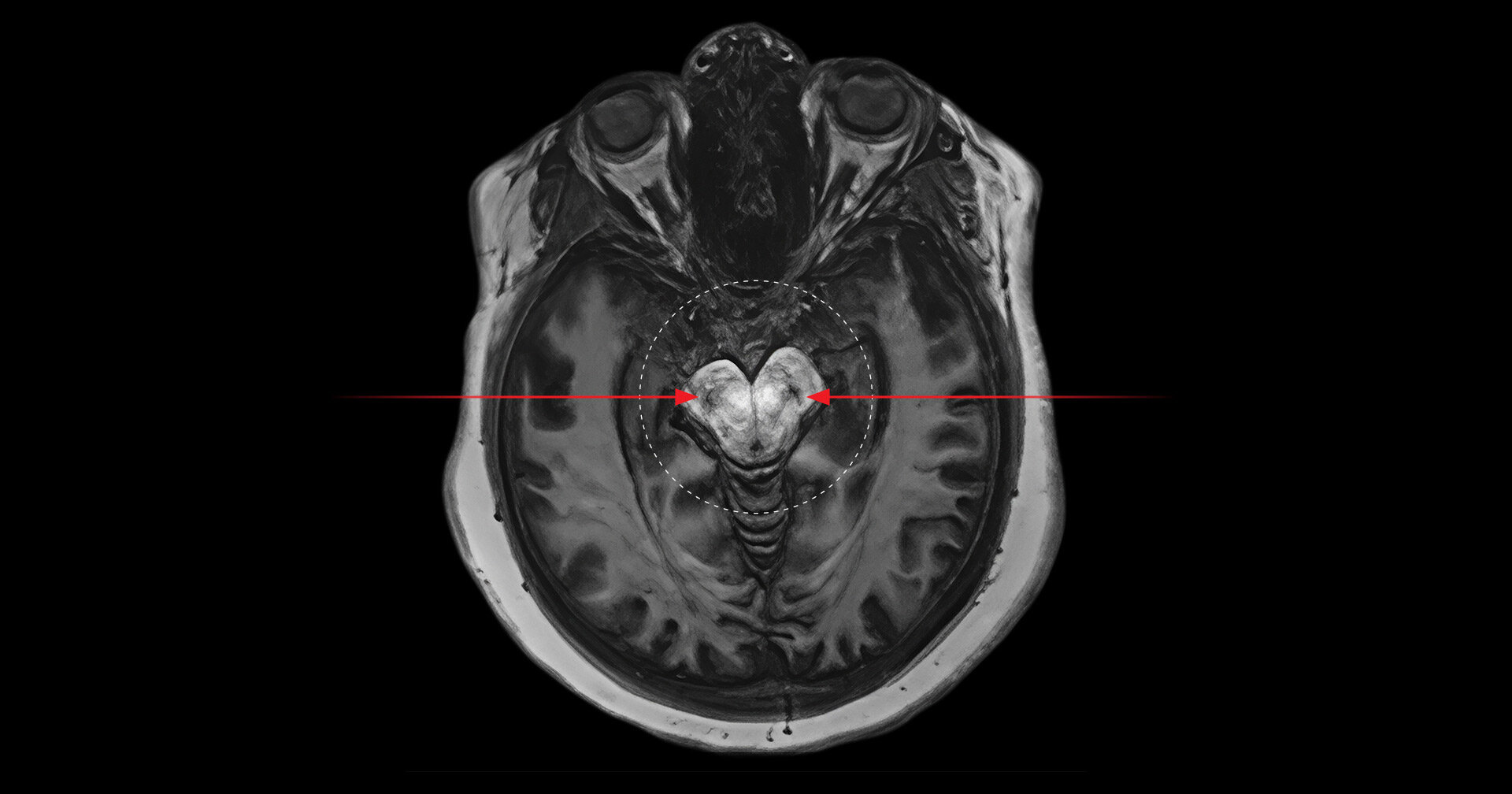

The real innovation lay in the imaging technique used: neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This non-invasive approach enables researchers to measure neuromelanin, a dark pigment that accumulates in the brain over time as a byproduct of dopamine metabolism.

“When there’s too much dopamine being produced, it leaves behind more neuromelanin,” explained Palaniyappan. “And that shows up as darker spots on the scans. In people who use cannabis excessively, those spots are darker than expected for their age—sometimes showing levels of pigment someone 10 years older would have.”

These “black spots” were especially concentrated in two areas of the midbrain—the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area (VTA)—regions intimately involved in the brain’s dopamine system and heavily implicated in psychotic disorders.

According to Dr. Ali Khan, professor at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and scientist at the Robarts Research Institute, these changes were observed regardless of whether the cannabis users had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. “This suggests that cannabis use alone may be enough to induce these dopamine-related brain changes,” he said.

Real-Life Consequences: What Clinicians Are Seeing

For clinicians on the front lines of mental health care, the study provides concrete biological evidence for what they’ve been witnessing for years: a surge in cannabis-induced psychosis cases, especially since the legalization of recreational cannabis in Canada in 2018.

“In recent years, we’re seeing more adolescents come in with one or two brief cannabis-induced psychotic episodes,” said Dr. Richard, another clinician affiliated with the study. “Then, not long after, they’ll experience a much more serious, persistent episode. We try to counsel them within that first episode—show them the areas of the brain being affected—so they understand the risk of pushing their brain toward a major psychotic break.”

The implications of the findings are especially concerning for teenagers and young adults, whose brains are still developing and are more sensitive to chemical changes. Frequent cannabis use during this critical developmental window could amplify the risk of long-term cognitive and psychiatric complications.

A Wake-Up Call for Public Health

Since the legalization of cannabis, many users have come to view it as a safe, natural remedy for everything from anxiety to insomnia. But this new research underscores a growing concern: while cannabis may be “natural,” its effects on the brain can be far from benign—particularly when used habitually and at high potency.

“This study really clarifies the biological mechanisms connecting cannabis and psychosis,” said Schaefer. “It’s not just anecdotal anymore. There’s a measurable change in the brain, and that’s a game-changer for how we talk about cannabis use in public health.”

With cannabis consumption on the rise—especially among young people—the findings couldn’t be more timely. According to Statistics Canada, cannabis use among those aged 18 to 24 has increased significantly since legalization, and emergency departments are seeing a marked rise in cannabis-related psychiatric visits.

“This isn’t about scaring people,” emphasized Jessica Ahrens, Ph.D. candidate at McGill and first author of the study. “It’s about giving them the information they need to make informed choices. We hope these findings help patients and healthcare providers better understand the implications of cannabis use and provide resources for alternative coping mechanisms.”

Looking Ahead: Research, Responsibility, and Regulation

While the study’s findings are compelling, they also raise new questions: Why are some people more vulnerable to dopamine dysregulation than others? Could genetic predisposition play a role? Are certain strains or potencies of cannabis more dangerous than others? How long-lasting are these changes in dopamine activity?

Researchers hope to expand future studies to include larger and more diverse populations, examine the effects of cannabis cessation on dopamine levels, and explore whether similar changes are seen with synthetic cannabinoids.

In the meantime, the message is clear: Cannabis use, particularly heavy and sustained use, is not without risk—especially for young brains and those predisposed to mental illness. And while cannabis may be decriminalized or even socially accepted, it deserves the same level of scrutiny and respect as any other psychoactive substance.

As public health systems adapt to this evolving landscape, the findings from this study could help shape future guidelines, clinical interventions, and educational campaigns. By illuminating the hidden biological consequences of excessive cannabis use, this research represents a crucial step toward protecting mental health in a post-legalization world.

Reference: Jessica Ahrens et al,Convergence of Cannabis and Psychosis on the Dopamine System, JAMA Psychiatry (2025). DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.0432 , jamanetwork.com/journals/jamap … /fullarticle/2832297