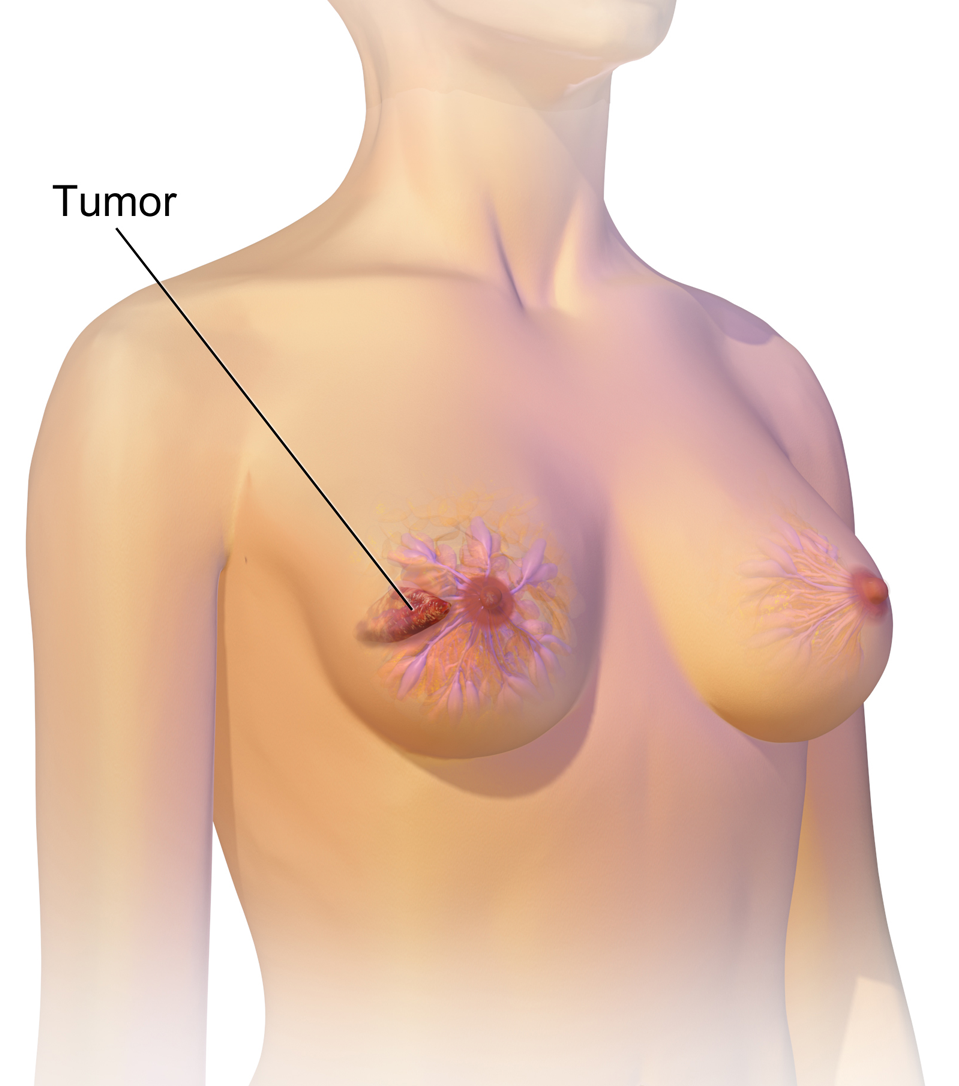

At its core, cancer is the tale of a cell that has forgotten how to die. It begins when a single cell, once a model citizen in the body’s intricate society, begins to rebel. It divides uncontrollably, refuses to follow orders, and disrupts the carefully tuned balance of tissue and function. In the case of breast cancer, this story unfolds within the glandular tissues of the breast—primarily in the ducts that carry milk or the lobules that produce it.

Breast cancer is not a singular disease but a complex family of disorders with many faces. Some grow slowly and remain localized for years. Others are aggressive, swiftly moving beyond the breast to infiltrate other parts of the body. What they all share is a common origin in the cellular architecture of the breast, and a betrayal of the genetic rules that govern healthy life.

For decades, scientists have worked to decode why some breast cells turn malignant. While no single cause exists, research has uncovered a rich tapestry of influences—from inherited genetic mutations to environmental exposures and hormonal changes. Breast cancer is personal, unpredictable, and shaped by countless variables.

The Genetic Blueprint that Shapes Destiny

One of the most powerful influences on breast cancer risk lies in the genetic code we inherit at birth. The most well-known culprits are mutations in two genes: BRCA1 and BRCA2. These genes usually act as cellular repair crews, fixing damaged DNA and maintaining genetic stability. But when mutated, they lose their protective function, dramatically increasing the likelihood that a person will develop breast or ovarian cancer.

Carriers of these mutations face a lifetime breast cancer risk as high as 70 percent. Yet, these mutations are rare. Most cases of breast cancer arise not from inherited genes, but from mutations acquired over a person’s lifetime—mistakes in cellular replication, damage from environmental toxins, or the gradual wear and tear of aging.

Genetics, however, doesn’t mean inevitability. Even in families with strong histories of breast cancer, lifestyle, screening, and early intervention can change the story. And for those without any known mutations, cancer can still strike—because while genes shape destiny, they do not write it in stone.

The Hormonal Tides that Influence Risk

The breast is a hormone-sensitive organ. Its development and function are deeply tied to the rhythmic dance of estrogen and progesterone. It is no surprise, then, that hormone exposure across a lifetime plays a pivotal role in breast cancer risk.

Early menarche and late menopause increase the window of estrogen exposure, nudging up the risk. So does late pregnancy or never having children. On the flip side, pregnancy and breastfeeding offer protective effects, possibly by reducing the number of lifetime ovulatory cycles or altering breast tissue in a way that makes it more resistant to transformation.

Postmenopausal hormone therapy, once widely prescribed to ease symptoms of aging, has also been implicated. Combination therapies that include both estrogen and progesterone are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer, especially when used long-term.

Yet, hormone-related risks are not absolute. They interact with other factors—genetics, environment, body weight—and understanding the nuance helps both individuals and clinicians make more informed decisions.

The Weight of Lifestyle and the Power of Choice

While we cannot change the genes we inherit or the age at which we first menstruate, many risk factors for breast cancer are modifiable. Lifestyle choices—seemingly small, daily decisions—can have significant effects on long-term cancer risk.

Excess body fat, particularly after menopause, increases breast cancer risk. Fat tissue becomes the body’s main source of estrogen after the ovaries stop producing it, and more fat means more estrogen, which can stimulate the growth of hormone-sensitive tumors. Obesity also fuels inflammation and insulin resistance—two more drivers of cellular damage.

Alcohol consumption is another key player. Even moderate drinking raises breast cancer risk, likely by increasing estrogen levels or causing direct DNA damage. Smoking, once more commonly associated with lung disease, is now also recognized as a contributor to breast cancer.

Physical activity offers powerful protection. Regular exercise not only helps maintain a healthy weight but also modulates hormone levels, reduces inflammation, and strengthens the immune system. Women who engage in consistent physical activity—whether walking, cycling, or dancing—tend to have lower rates of breast cancer, regardless of age or background.

Diet plays a more complex role. While no single food guarantees protection or doom, diets rich in fruits, vegetables, fiber, and healthy fats (like those found in olive oil and nuts) appear beneficial. Ultra-processed foods, red meats, and high-sugar diets are associated with higher cancer risks, though the mechanisms remain under investigation.

The Enigma of Environmental Exposure

Modern life brings with it a vast array of chemicals—some beneficial, others potentially harmful. Among these are endocrine disruptors: compounds that mimic or interfere with the body’s natural hormones. Found in plastics, pesticides, cosmetics, and even some household cleaners, these substances have raised concern among scientists for their potential role in breast cancer.

Bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and parabens are among the most studied. Animal models suggest these chemicals can alter breast development and increase susceptibility to cancer, especially with early-life exposure. In humans, the evidence is more circumstantial but compelling enough to drive public health campaigns for reduction and safer alternatives.

Radiation is another known risk factor. Women exposed to high levels of ionizing radiation, especially during childhood or adolescence, face higher breast cancer risks later in life. This has been observed in atomic bomb survivors and patients treated with radiation for conditions like Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Fortunately, modern medical imaging uses much lower doses and strict protocols to minimize unnecessary exposure.

The Landscape of Risk Across Age and Ethnicity

Breast cancer does not affect all people equally. Age is the single most significant risk factor, with the vast majority of cases occurring in women over 50. As the body ages, cells accumulate mutations, and the mechanisms that guard against them grow less efficient.

But racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer also reveal troubling disparities. White women are slightly more likely to develop breast cancer overall, but Black women are more likely to die from it. They are also more frequently diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, a particularly aggressive form that does not respond to hormone therapy.

These disparities are not purely biological. They reflect a confluence of social, economic, and systemic factors—access to care, cultural beliefs, healthcare bias, and the structural inequities that affect everything from diet to stress to timely diagnosis.

Latina, Asian American, and Native American women face their own unique patterns of risk and detection. For instance, breast cancer rates in Asian American women are generally lower, but rising steadily with Westernized lifestyles. Each community brings its own challenges and strengths, and personalized public health efforts are essential to closing the gap.

The Lifesaving Power of Screening and Early Detection

Catching breast cancer early is often the difference between life and death. When detected in its earliest stages, breast cancer has a five-year survival rate of over 90 percent. But as it spreads to lymph nodes or distant organs, that rate drops sharply.

Mammography remains the gold standard for breast cancer screening. By using low-dose X-rays to image breast tissue, it can detect tumors too small to feel. Regular screening allows doctors to identify cancers before symptoms arise, enabling earlier, less aggressive treatment.

Most guidelines recommend that women begin regular mammograms between the ages of 40 and 50, continuing every one to two years depending on individual risk factors. For those with dense breast tissue—a condition that can make tumors harder to spot—additional imaging such as ultrasound or MRI may be recommended.

Clinical breast exams and breast self-awareness also play roles in detection. While self-exams have not consistently reduced mortality in large studies, being familiar with the normal look and feel of one’s breasts helps individuals notice changes and seek medical attention sooner.

Emerging technologies promise to refine screening even further. Digital breast tomosynthesis (3D mammography), contrast-enhanced mammography, and artificial intelligence-driven image analysis are expanding the frontier of what’s possible in early detection.

The Rise of Personalized Screening Strategies

One-size-fits-all screening is slowly giving way to a more tailored approach. Risk assessment tools—such as the Gail model, Tyrer-Cuzick model, and genetic testing—allow physicians to estimate an individual’s likelihood of developing breast cancer. This data can inform not only when to start screening but which modalities to use.

For women with BRCA mutations or strong family histories, annual MRI scans starting in early adulthood may be appropriate. Others may benefit from genetic counseling, chemoprevention (such as tamoxifen), or even prophylactic mastectomy in rare cases.

Conversely, for women at low risk, spacing out mammograms or starting later may be sufficient. These personalized approaches aim to maximize benefit while minimizing harm—such as overdiagnosis, anxiety, or unnecessary procedures.

The future of screening may even lie in blood. Liquid biopsy technologies, which analyze DNA fragments shed by tumors into the bloodstream, are being studied as potential early detection tools. While not yet ready for widespread use, they represent an exciting glimpse of what’s to come.

Beyond Screening to Prevention and Empowerment

Screening saves lives, but prevention offers the holy grail: stopping cancer before it starts. While no strategy guarantees immunity, a substantial portion of breast cancer cases could be prevented through healthy lifestyle choices.

Regular physical activity, limited alcohol, maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding tobacco, and eating a balanced diet are all proven tools of risk reduction. For high-risk individuals, medications such as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and aromatase inhibitors can reduce the chance of developing hormone-positive breast cancers.

Public health also plays a crucial role. Access to affordable screenings, education campaigns, community-based interventions, and policy changes can reshape the broader risk environment. For example, banning certain chemicals, improving food quality in low-income neighborhoods, and providing paid time off for screenings can all have measurable impact.

Empowerment is essential. When individuals understand their own risk, know the signs and symptoms of breast cancer, and have the resources to act, outcomes improve. Knowledge is not just power—it’s protection.

The Ongoing Journey of Research and Hope

Breast cancer is not a monolith. It is ductal or lobular, hormone-positive or triple-negative, HER2-driven or not. Each subtype behaves differently, responds to different treatments, and requires unique strategies. Research is steadily unraveling this complexity.

Targeted therapies, like HER2 inhibitors, PARP inhibitors for BRCA-related cancers, and CDK4/6 inhibitors for certain hormone-receptor cancers, are extending survival and reducing recurrence. Immunotherapy, while still in early stages for breast cancer, holds promise—particularly for triple-negative cases.

Precision oncology, where treatments are matched to the genetic profile of a person’s tumor, is transforming what was once a shotgun approach into a guided missile. Clinical trials continue to test new combinations and novel agents, bringing us closer to the dream of curing—even preventing—this multifaceted disease.

A Disease Transformed and a Future Reimagined

Breast cancer is no longer the silent killer it once was. It is a disease transformed by science, advocacy, and the resilience of those who face it. Survival rates have improved, stigmas have faded, and pink ribbons have become powerful symbols of solidarity and strength.

Yet, the work is far from over. Disparities in care persist, research gaps remain, and the emotional toll of diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship continues to ripple through millions of lives. The fight against breast cancer is not just a medical challenge—it is a human one.

And so we march forward, armed with knowledge, guided by empathy, and fueled by the belief that the end of breast cancer is not a fantasy but a future we can build—one discovery, one screening, one empowered life at a time.