Pheromones are a favorite topic in pop culture and science fiction. In romantic comedies and TV dramas, they’re often portrayed as invisible love potions, driving attraction and chemistry. But in real life, the question of whether humans communicate through pheromones—chemicals that can influence the behavior or physiology of others of the same species—has remained hotly debated. Until now, the science has mostly said “not quite.”

But a new study from the University of Tokyo suggests there may be more truth to the idea than we thought—not through magical love dust, but via subtle shifts in body odor that appear to affect how men feel, perceive, and even relax. The research doesn’t prove the existence of human pheromones, but it does reveal how smell might shape social and emotional interactions between men and women in profound and surprising ways.

The Hidden Chemistry of Attraction

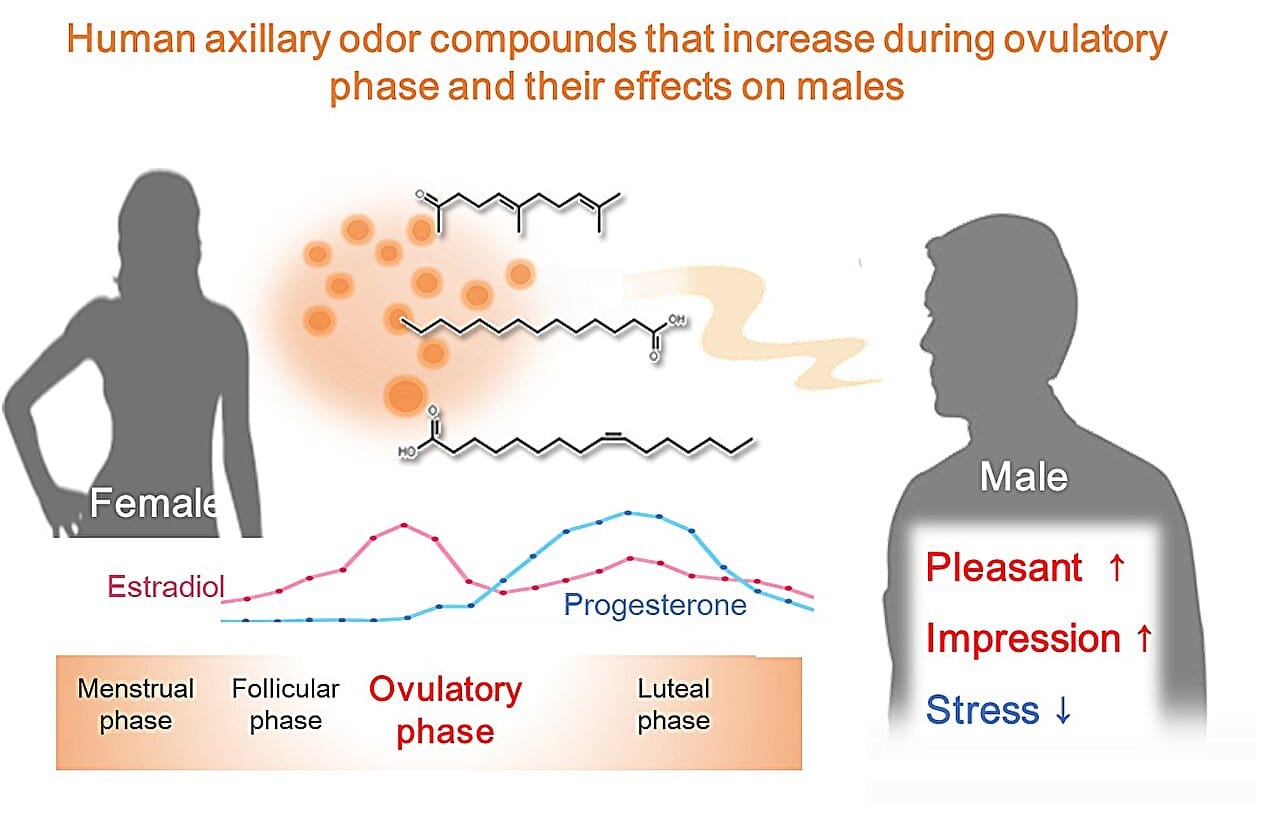

The study, conducted by the Department of Applied Biological Chemistry and the International Research Center for Neurointelligence (WPI-IRCN), focused on the changes in women’s natural body odor throughout the menstrual cycle, particularly during ovulation. Using an advanced chemical analysis technique called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, researchers identified three specific compounds that increased in female armpit odor during the ovulatory phase.

That timing matters. Ovulation is when a woman is most fertile, and in many animal species, this phase triggers physiological and behavioral cues in potential mates. But do humans respond in a similar way—perhaps without even realizing it?

To test this, researchers collected armpit odor samples from more than 20 women at different phases of their menstrual cycles. It was a slow and meticulous process. Each participant had to be closely monitored for ovulatory signs—body temperature, hormonal fluctuations, and cycle timing—so that samples could be collected with precision. On average, it took more than a month per participant to complete the collection process.

Once the odors were isolated, they were added to a synthetic base (a neutral armpit-like smell), and then presented to male participants in a double-blind experiment. The men were asked to sniff these samples and rate them, along with images of women’s faces shown alongside. The results were both surprising and revealing.

Less Stress, More Attraction

When exposed to the ovulatory scent mix, men rated the odors as less unpleasant compared to control samples. But it wasn’t just about smell—they also rated the accompanying women’s faces as more attractive and more feminine. It seemed that something in the scent was quietly tuning their perceptions, even though they were unaware of what exactly they were smelling.

Even more striking was what happened inside the men’s bodies. The researchers measured the levels of salivary amylase, a biomarker of stress, before and after exposure. In men who smelled the ovulation-scented compounds, the levels of amylase were significantly lower. In other words, the scents appeared to relax them.

That finding is particularly intriguing. It suggests that scent—especially subtle, naturally emitted body odor—might not only influence attraction but also stress, mood, and possibly even emotional bonding. This goes far beyond a romantic cliché. It hints at a biological channel of communication most of us aren’t consciously aware of.

Are These Human Pheromones? Not Quite.

Despite the dramatic results, the research team is careful not to overstate the implications. Professor Kazushige Touhara, who led the study, emphasizes that while these compounds may resemble pheromones in how they subtly influence behavior and physiology, they don’t meet the strict definition of the term.

“In the classical sense,” Touhara explained, “pheromones are species-specific chemical substances that trigger predictable responses. What we found are ovulation-linked compounds that may influence perception and stress, but we can’t yet call them human pheromones.”

Instead, he refers to them as “pheromone-like.” They influence behavior, but it’s unclear whether their effect is universal across all men, or whether cultural and genetic factors play a role. Also, unlike pheromones in animals, which often trigger fixed actions (like mating rituals or aggression), the effects here are subtler—tweaks in how people feel or perceive, rather than direct commands to act.

A Study Built on Precision and Patience

To achieve such delicate insights, the research demanded extraordinary care and control. First author Nozomi Ohgi, who was a graduate student in Touhara’s lab at the time, recalled the enormous challenge of tracking female participants’ cycles, collecting scent samples at exactly the right times, and maintaining rigorous standards to prevent contamination or bias.

“We interviewed each woman regularly about body temperature and other indicators of ovulation,” she said. “It was time-consuming and demanded real dedication.” This degree of granularity is rare in studies of human scent and made the findings that much more reliable.

The team also ensured the men participating in the experiment had no idea what they were smelling or why. Some were even given completely neutral or unscented samples, allowing the researchers to isolate the effects of the specific ovulatory compounds.

Smell: The Forgotten Sense of Communication

For most of human history, vision and hearing have dominated our understanding of communication. But in recent years, a growing body of research has begun to uncover how smell—long underestimated—plays a powerful role in social behavior, memory, emotion, and attraction.

Unlike sight and sound, which are filtered through various layers of brain processing, scent takes a direct route. It travels from the nose to the olfactory bulb, which is connected to the limbic system—the emotional core of the brain. This might explain why certain smells evoke strong memories, gut feelings, or even sudden emotional shifts.

The University of Tokyo study adds weight to the idea that humans may still be quietly exchanging emotional information through body odor—particularly during moments of biological significance like ovulation.

Future Directions: Into the Brain, Across Cultures

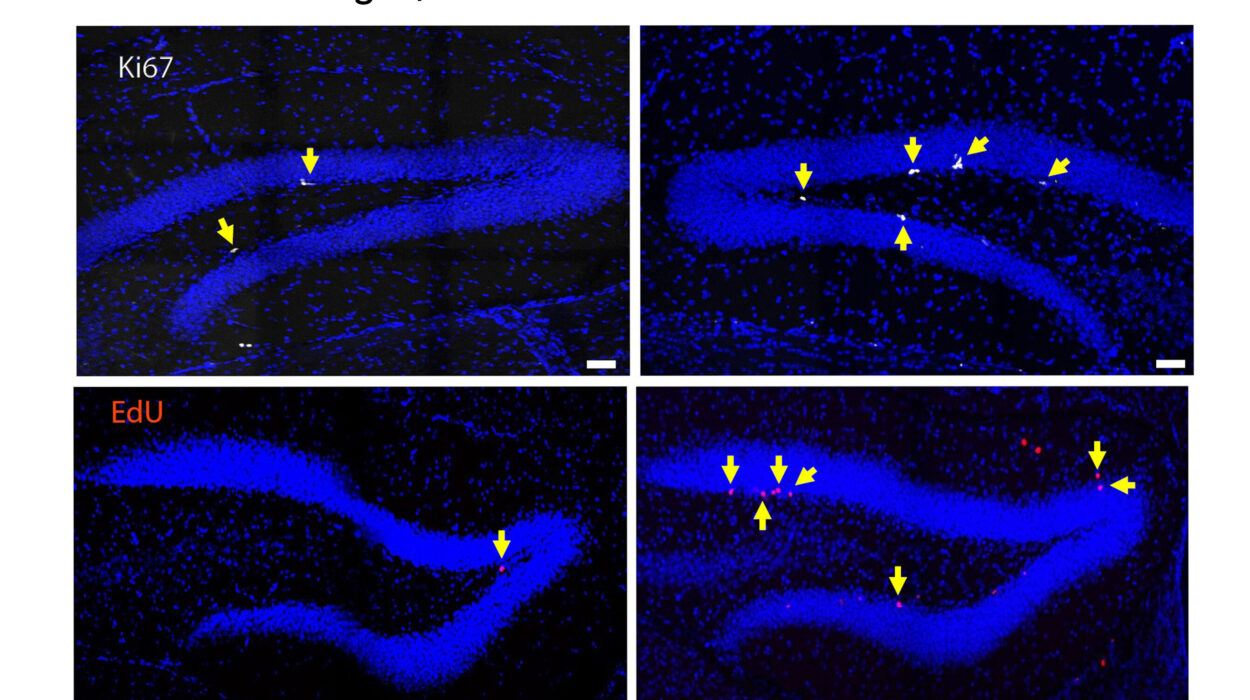

This is just the beginning of the research. Touhara and his team plan to go deeper—both figuratively and literally. They hope to study how these scent compounds affect brain activity in real time, using imaging techniques like fMRI. By watching how the brain responds to these ovulatory odors, scientists could uncover the specific circuits involved in attraction, stress, or emotional processing.

Another key goal is to broaden the participant pool. So far, the study has only tested certain groups of people, and it’s possible that genetics or cultural background could influence how individuals respond to scent. Future studies will aim to test more diverse populations to see whether the same effects hold true across different ethnicities and environments.

This is particularly important because the human experience of smell is deeply shaped by cultural context. For example, what one culture considers a “pleasant” body odor might be considered neutral—or even unpleasant—in another. Untangling the universal from the subjective will be critical in understanding just how deep the roots of scent-based communication go.

Subtle Signals, Profound Possibilities

While the findings don’t confirm the existence of human pheromones, they do suggest that we are more influenced by scent than we think. The notion that women’s body odor changes during ovulation and can influence male emotions and perceptions, even reducing stress, opens a new dimension in understanding human social behavior.

In a world increasingly dominated by screens and digital messages, it’s a poetic reminder that biology still speaks in whispers—in the space between a breath and a glance, in the scent of skin under sunlit air. These subtle cues may not command us, but they shape us. They steer impressions, soften moods, and draw the edges of invisible connections.

What began as a question of chemistry has become a story of communication—one that links the oldest parts of the brain to the newest mysteries of the heart.

More information: Human ovulatory phase-increasing odors cause positive emotions and stress-suppressive effects in males, iScience (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113087