The female body is extraordinary—not only because of the strength it demonstrates in daily life, but also because of the intricate biological rhythms that shape its energy, mood, and performance. Among these rhythms, the menstrual cycle is one of the most powerful. It is not simply a monthly event marked by bleeding; it is a dynamic cycle of hormonal changes that influence every aspect of health—physical, emotional, and even social.

For years, conversations about exercise and menstruation have been hushed, hidden, or dismissed. Too often, women have been told to “push through” their discomfort, or worse, made to feel weak for acknowledging how their cycle affects their body. But science now validates what women have always known: hormones matter, and they change how we feel, recover, and perform.

This article dives deep into how you can align your training with the phases of your menstrual cycle. With more than just practical tips, it aims to honor your body, help you understand its fluctuations, and show how exercise can be your ally, not your enemy, throughout every stage of your cycle.

Understanding the Menstrual Cycle and Hormones

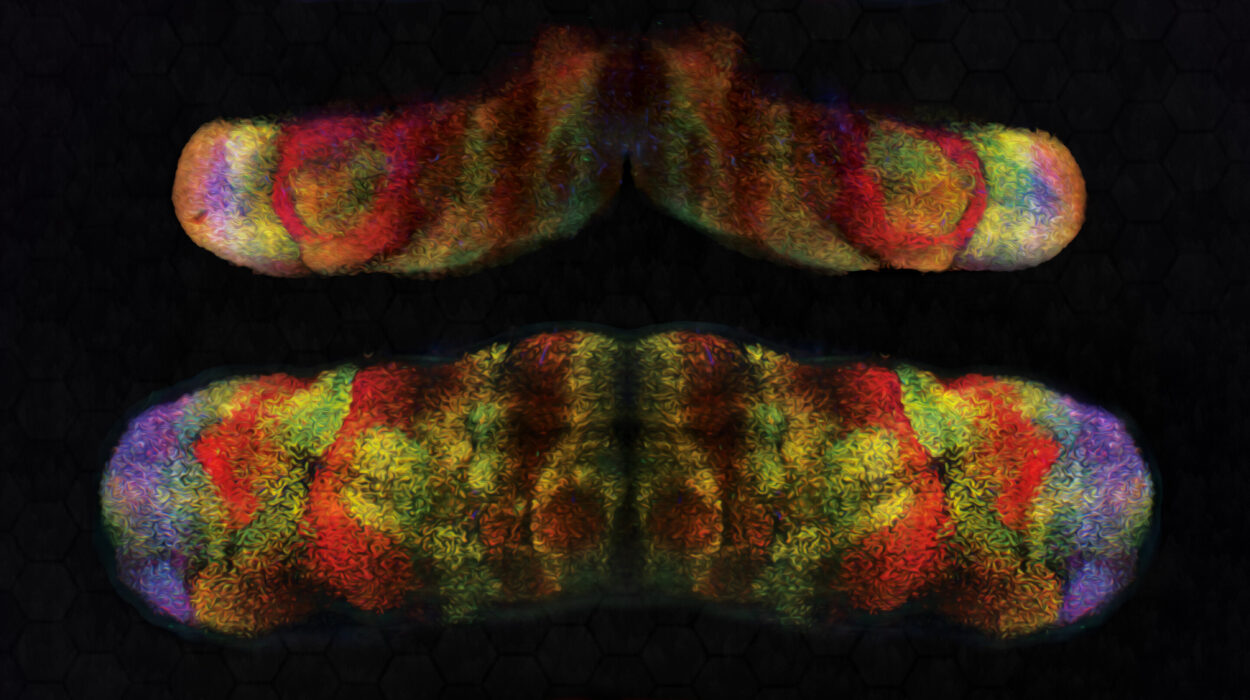

Before exploring how to tailor exercise, it’s essential to understand the biology of the menstrual cycle. A typical cycle lasts around 28 days, though it can range from 21 to 35 days. It is divided into four main phases: menstrual, follicular, ovulatory, and luteal. Each phase is orchestrated by a delicate interplay of hormones—primarily estrogen and progesterone, with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) playing supporting roles.

- Menstrual phase (Days 1–5): This begins with bleeding, when progesterone and estrogen are at their lowest. Energy may feel drained, cramps may occur, and emotions can feel raw.

- Follicular phase (Days 1–13, overlapping with menstruation): Estrogen begins to rise, stimulating the growth of follicles in the ovaries. Energy, motivation, and mood often improve steadily.

- Ovulatory phase (Around Day 14): A surge of estrogen and LH triggers ovulation—the release of an egg. This is when many women feel strongest, most energetic, and most confident.

- Luteal phase (Days 15–28): Progesterone rises to prepare the body for a potential pregnancy. If pregnancy does not occur, progesterone and estrogen drop, leading to PMS symptoms such as bloating, mood swings, and fatigue.

These hormonal fluctuations aren’t just about reproduction; they affect metabolism, muscle recovery, pain tolerance, coordination, and even motivation. Recognizing this can turn exercise from a struggle into a powerful way of working with your body rather than against it.

Exercise During the Menstrual Phase: Rest, Restore, and Gentle Strength

Bleeding days are often the most challenging part of the cycle. Cramps, headaches, fatigue, and emotional lows can all make movement feel unappealing. However, research shows that gentle, mindful exercise can actually reduce symptoms by increasing blood flow, releasing endorphins, and lowering stress hormones.

Low-intensity activities such as walking, restorative yoga, or light cycling can soothe discomfort. Some women also find gentle strength training effective, as long as intensity is adjusted to match their energy. The key is not to push yourself into exhaustion but to honor your body’s need for rest while still giving it the benefits of movement.

Hydration and nutrition are especially important here, as blood loss can lower iron levels. Exercises that promote circulation, such as stretching or Pilates, can also relieve bloating and cramps. Most importantly, the menstrual phase calls for compassion—if your body tells you to rest, listen. Rest is not weakness; it is part of strength.

Exercise During the Follicular Phase: Building Power and Confidence

As bleeding ends, energy begins to rise. Estrogen levels increase steadily, improving insulin sensitivity, supporting muscle repair, and enhancing motivation. This makes the follicular phase a golden window for progressive training.

Your body is primed to build lean muscle and handle more intense sessions. High-intensity interval training (HIIT), heavy strength training, and endurance runs often feel more manageable here. Studies have shown that women may experience greater gains in muscle strength during this phase, likely due to the anabolic effects of estrogen.

Mental clarity also improves, making it a great time to set new goals, learn new skills, or refine complex movements in sports. This is a time when the body feels vibrant, responsive, and strong. Taking advantage of this phase can build momentum that carries into the rest of the cycle.

Exercise During the Ovulatory Phase: Harnessing Peak Performance

Ovulation is often the phase when women feel most powerful. Estrogen peaks, LH surges, and testosterone levels rise slightly, enhancing strength, speed, and coordination. Confidence may be at an all-time high, making it a perfect time to push limits, test personal records, or compete.

Athletes often notice they perform their best during ovulation. Reaction times are sharper, endurance feels higher, and recovery seems smoother. This is the moment to embrace vigorous training—whether it’s sprinting, lifting heavy weights, or tackling demanding workouts.

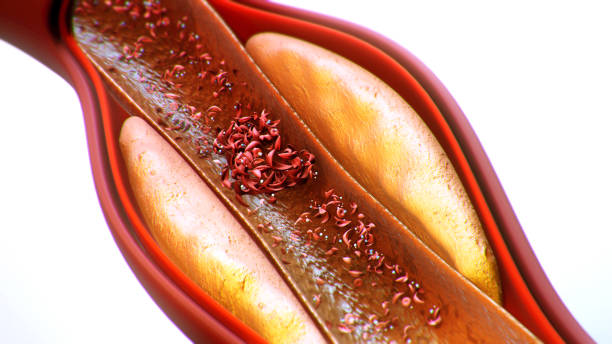

However, ovulation also carries risks. High estrogen levels can increase joint laxity, particularly in the knees, raising the risk of injuries such as ACL tears. Warm-ups, mobility work, and proper form become especially crucial during this time. Strengthening the muscles around joints and paying attention to alignment can help safeguard against injuries while still enjoying peak performance.

Exercise During the Luteal Phase: Balancing Effort and Recovery

The luteal phase can be unpredictable. Progesterone rises, raising body temperature, slowing digestion, and sometimes leading to bloating, fatigue, or mood fluctuations. Workouts may suddenly feel harder, recovery slower, and motivation weaker.

Yet, this phase does not mean giving up on exercise. Instead, it’s about adjusting expectations. Moderate-intensity workouts such as steady-state cardio, swimming, or circuit training may feel more sustainable. Strength training is still beneficial, though recovery should be prioritized.

Some women experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS) with symptoms like irritability, cravings, and anxiety. Exercise, particularly aerobic activities, can alleviate these symptoms by boosting serotonin and reducing cortisol. Yoga, Pilates, and meditation-based practices can also bring balance and calm during this emotionally sensitive time.

Nutrition becomes especially important: focusing on magnesium-rich foods for mood regulation, complex carbohydrates for energy, and adequate hydration to combat water retention. Sleep, too, plays a central role in supporting the body through this hormonally demanding phase.

Exercise, Pain, and Period Symptoms

One of the most common questions is whether exercise can reduce period pain. The answer, supported by research, is yes. Regular physical activity increases circulation, reduces stress, and releases endorphins—natural painkillers. Women who exercise consistently often report lighter symptoms over time compared to those who remain sedentary.

For those with conditions like endometriosis or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), exercise can also be beneficial in managing symptoms, though adjustments may be necessary. Low-impact movement may feel more sustainable, and professional guidance can be invaluable in tailoring training plans.

Importantly, exercise should never exacerbate pain. If cramps are severe, rest may be the most healing choice. Listening to your body and adjusting accordingly is always the priority.

Emotional Health, Body Image, and Training Cycles

The menstrual cycle doesn’t just affect the body—it also influences emotions and self-perception. During the luteal and menstrual phases, when hormones dip, women may feel less confident, more self-critical, or discouraged about performance. These feelings are real and valid.

Exercise can be an anchor during these times, not only by boosting endorphins but also by reinforcing body appreciation. Viewing training as a way of caring for yourself, rather than punishing yourself, transforms exercise into an act of self-love.

Shifting goals throughout the cycle—from performance-based during ovulation to restorative during menstruation—helps reframe fluctuations not as weaknesses but as natural rhythms. This mindset fosters resilience, compassion, and long-term sustainability.

The Science of Recovery and Adaptation

Recovery is not static; it is shaped by hormones. Estrogen enhances muscle repair and reduces inflammation, making recovery faster in the follicular phase. Progesterone, however, can slow recovery in the luteal phase, which may explain why workouts feel tougher.

Understanding this allows women to time their training peaks wisely. High-intensity sessions may be best clustered in the follicular and ovulatory phases, with active recovery emphasized in the luteal phase. Adequate sleep, hydration, and nutrient support become non-negotiable in the second half of the cycle.

By aligning training with recovery patterns, women can avoid burnout, reduce injury risk, and maximize gains.

Nutrition Across the Cycle

Fueling the body appropriately during each phase enhances both exercise and well-being.

- Menstrual phase: Focus on iron-rich foods (spinach, red meat, lentils) to replenish blood loss. Hydrating herbal teas may reduce bloating and cramps.

- Follicular phase: High-protein meals support muscle growth, while complex carbohydrates provide steady energy for intense workouts.

- Ovulatory phase: Anti-inflammatory foods (berries, fatty fish, leafy greens) support recovery during peak performance.

- Luteal phase: Magnesium (nuts, seeds, dark chocolate) helps with PMS, while complex carbs stabilize mood. Avoiding excessive caffeine and sugar reduces bloating and irritability.

These are not rigid rules but guidelines that respect how the body’s needs shift with hormones.

Breaking the Stigma Around Periods and Exercise

For too long, periods have been stigmatized, treated as a weakness, or ignored in training programs. Yet, athletes and everyday women alike are proving that menstruation is not a barrier but a source of strength when understood correctly.

Professional sports teams now track menstrual cycles to optimize training schedules, with research showing improved performance and reduced injuries. This recognition validates what women have always known—that their cycles matter and deserve respect.

Breaking the stigma begins with open conversations. Coaches, trainers, and healthcare providers must recognize the menstrual cycle as central to women’s health and performance, not as an inconvenience to be brushed aside. Women themselves must feel empowered to speak about their needs without shame.

Beyond the Cycle: Pregnancy, Postpartum, and Menopause

While this article focuses on the menstrual cycle, it’s important to acknowledge that women’s bodies move through many reproductive stages. Pregnancy changes exercise needs dramatically, as does postpartum recovery. Menopause, with its decline in estrogen, brings new challenges for bone health, metabolism, and mood.

In every stage, the principle remains the same: listen to your body, honor its rhythms, and use exercise as a tool for health and empowerment. Biology may shift, but movement remains a constant ally.

Conclusion: Training With, Not Against, Your Cycle

The menstrual cycle is not a limitation—it is a rhythm, a wave, a guide. When women learn to train with it instead of against it, they unlock new levels of performance, health, and self-compassion.

Periods do not weaken women; they remind us of the extraordinary resilience of the body. Each phase, from the quiet fatigue of menstruation to the fiery energy of ovulation, offers its own gifts. Exercise is the thread that ties these phases together, offering relief, strength, and joy.

To move with your cycle is to live in harmony with yourself. It is a declaration that your body is not an obstacle but a miracle. And when training honors that miracle, it becomes more than fitness—it becomes freedom.