Few words in the English language carry the emotional weight of “cancer.” It is a word whispered in hospital corridors, scribbled with trembling hands in search engine bars at midnight, and choked back in conversations between loved ones. It can stop time, divide life into “before” and “after,” and summon fear, confusion, and defiance in equal measure. But despite its terrifying reputation, cancer is not a singular monster. It is not one disease but many, not a death sentence but a complex biological puzzle—one that science has been striving to solve for centuries.

To understand cancer is to glimpse the invisible world within us: the chaotic realm of cells and molecules, of growth gone wrong and healing turned hostile. It is a story of betrayal at the most fundamental level of life, and yet, it is also a story of hope—because the more we understand it, the more powerful our response becomes.

What Exactly Is Cancer?

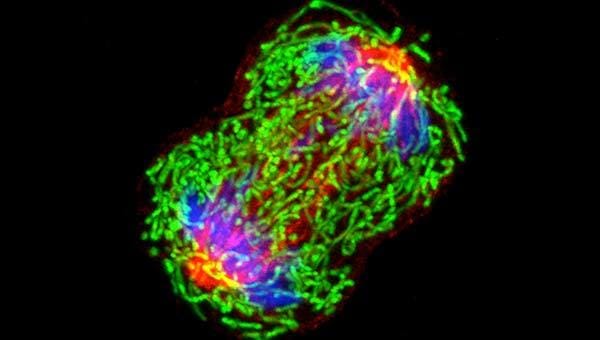

At its core, cancer is a disease of uncontrolled growth. Our bodies are made of trillions of cells, each programmed to grow, divide, and die in a tightly regulated cycle. This process is orchestrated by genetic instructions encoded in our DNA. But sometimes, due to mutations—whether from inherited genes, environmental exposure, or simple chance—cells begin to ignore these rules. They divide when they shouldn’t, refuse to die when they should, and begin to accumulate in places they don’t belong.

The result is a mass of rogue cells, a tumor. Some tumors remain benign—they grow slowly and stay localized. Others become malignant, meaning they invade surrounding tissues and can even travel to distant parts of the body in a process called metastasis. When this happens, the disease becomes far more dangerous, not because the cancer cells themselves are foreign invaders, like viruses or bacteria, but because they are our own cells, gone awry.

What makes cancer especially challenging is its diversity. There is no single “cancer”—there are more than 100 distinct types, each with its own behavior, causes, and vulnerabilities. A skin cancer behaves very differently from a brain tumor or leukemia. Even within one organ, cancers can differ dramatically depending on which cell type they arise from and which mutations they carry. That’s why cancer is more accurately referred to as a group of related diseases.

The Cellular Betrayal: How Cancer Begins

All cancers begin with a single cell. One cell, somewhere in the body, accumulates enough genetic damage to break free from the normal controls that keep it in check. This damage might be caused by radiation, chemicals, chronic inflammation, viruses, or inherited mutations. Sometimes, no obvious cause is found at all.

At the heart of this transformation is the cell’s DNA. Mutations can affect oncogenes, which promote cell division, or tumor suppressor genes, which inhibit it. When these genes are altered in the wrong way, the cell becomes unbalanced—like a car with a stuck accelerator and no brakes. Over time, more mutations accumulate, turning an ordinary cell into a cancerous one.

One of the most dangerous features of cancer cells is their ability to evade apoptosis, the programmed cell death that eliminates damaged cells. Normally, when something goes wrong inside a cell, it self-destructs to protect the body. Cancer cells disable this safety mechanism, allowing them to persist and multiply endlessly.

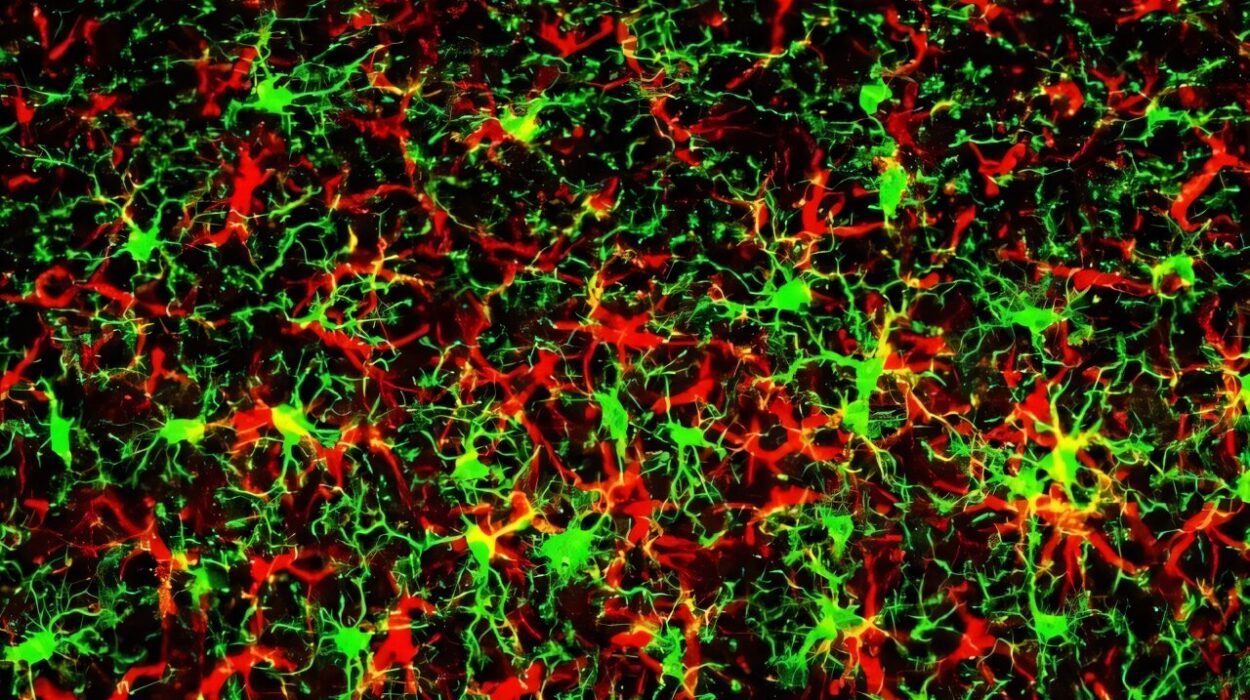

They also co-opt the body’s own systems. They attract blood vessels to feed their growth, hide from the immune system, and even rewire their metabolism to support rapid division. It’s no wonder that scientists describe cancer as “the emperor of all maladies,” a term made famous by physician and author Siddhartha Mukherjee. It is a disease that rewrites the rules of biology.

Different Faces of Cancer: A Spectrum of Diseases

Cancer can strike anywhere in the body, and its form depends on where it begins and how it behaves. Carcinomas are the most common type and originate in epithelial cells—the cells that line organs and skin. These include breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancers. Sarcomas arise in connective tissues like bone, muscle, or fat. Leukemias are cancers of the blood, originating in bone marrow and leading to the overproduction of abnormal white blood cells. Lymphomas affect the lymphatic system, a key part of the immune network.

There are also rarer cancers like glioblastoma (a deadly brain cancer), mesothelioma (linked to asbestos exposure), and pancreatic cancer, which is notoriously difficult to detect early. Each cancer has its own prognosis, treatment options, and survival rates. Even within a single type, subtypes exist that respond differently to therapies. For example, breast cancer can be estrogen receptor-positive or triple-negative, each with distinct treatment paths.

This diversity is why precision medicine—treating the specific genetic makeup of a tumor—is becoming so important. No two cancers are exactly alike, and the future of treatment lies in tailoring therapies to each patient’s unique disease.

What Causes Cancer?

The causes of cancer are as varied as the disease itself. Some are inherited. Others are acquired through life. But all involve damage to DNA that alters how cells grow and divide.

Tobacco remains the single largest preventable cause of cancer. Smoking introduces a cocktail of carcinogens into the lungs, dramatically increasing the risk of lung cancer, throat cancer, and many others. Ultraviolet radiation from the sun damages skin cells, leading to melanoma and other skin cancers. Excessive alcohol, poor diet, obesity, and lack of physical activity also raise the risk of various cancers.

Certain viruses and bacteria are carcinogenic. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a major cause of cervical and throat cancers. Hepatitis B and C viruses can lead to liver cancer. Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that infects the stomach, has been linked to gastric cancer. Vaccination and early detection can significantly reduce these risks.

Some people inherit mutations that increase their cancer risk. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations, for example, significantly raise the chances of breast and ovarian cancer. But having a mutation is not a guarantee—it only increases susceptibility. Environment, lifestyle, and chance still play crucial roles.

Age is also a major factor. Most cancers occur later in life, simply because the longer we live, the more time our cells have to accumulate damage. Cancer is, in some ways, a consequence of living long enough for the machinery of our biology to wear down.

The Emotional Earthquake: A Diagnosis

A cancer diagnosis is more than a medical event—it is a profound psychological rupture. In a single moment, the future becomes uncertain, the body becomes suspect, and life is forever divided into before and after. The shock is often followed by a flood of questions: Will I survive? What are my options? How will this affect my family? Why me?

The emotional toll of cancer is immense, not just for patients but for their loved ones. Anxiety, depression, and existential dread are common. Some find strength in faith or philosophy. Others lean on friends, support groups, or therapists. There is no “right” way to cope, only the deeply human process of navigating the unknown.

Doctors and nurses are not just providers of treatment—they become guides through a landscape of fear, hope, statistics, and decisions. Communication is critical. A diagnosis is not the end of the road—it is the beginning of a journey, one that may involve surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy, and more.

The Arsenal of Treatment: Fighting Back

Modern cancer treatment is more powerful and diverse than ever before. The choice of therapy depends on the type of cancer, its stage, location, genetic profile, and the overall health of the patient.

Surgery remains one of the oldest and most effective treatments. If a tumor is localized and operable, removing it can often lead to a cure. Advances in minimally invasive and robotic surgery have made procedures safer and recovery faster.

Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams to kill cancer cells or shrink tumors. It is precise and often used alongside other treatments. However, it can also damage healthy tissue, leading to side effects like fatigue and skin irritation.

Chemotherapy involves powerful drugs that target rapidly dividing cells. It is systemic, meaning it affects the whole body. While effective, chemotherapy is notorious for its side effects—nausea, hair loss, immune suppression—because it can’t always distinguish between cancerous and healthy fast-growing cells.

Targeted therapies aim to strike cancer cells at specific vulnerabilities, often by interfering with proteins or genes that the tumor depends on. These treatments tend to have fewer side effects and are tailored to the molecular profile of the cancer.

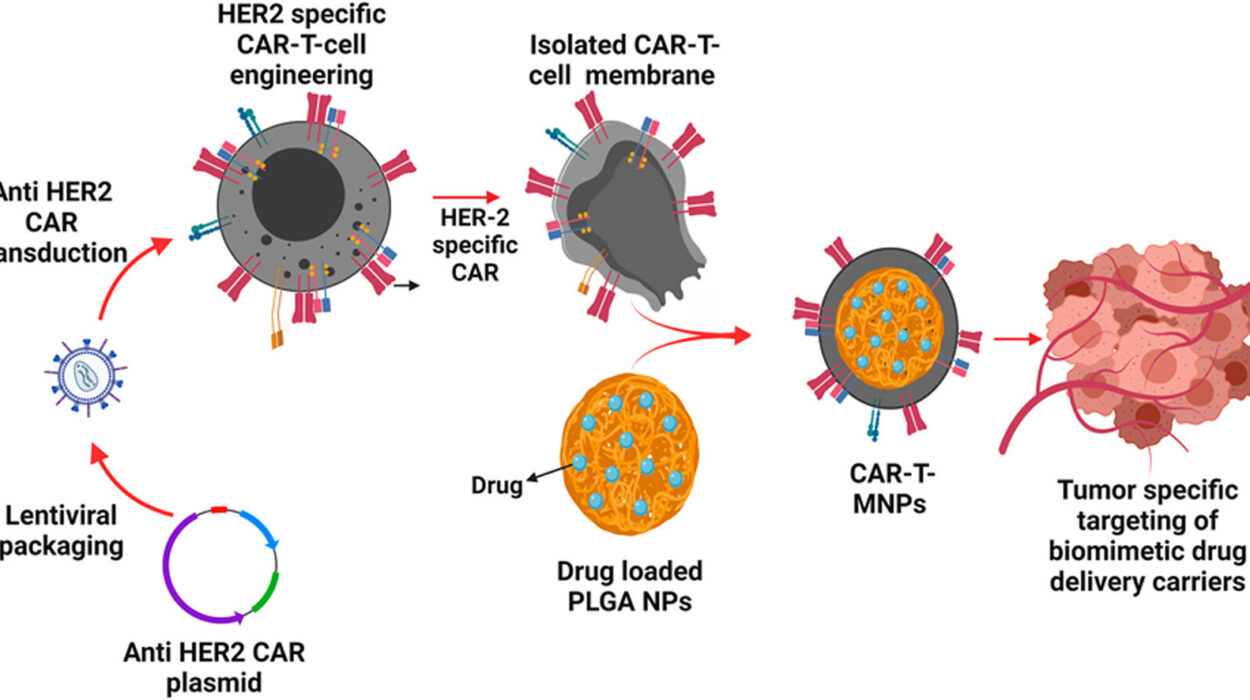

Immunotherapy is one of the most exciting recent developments. It helps the body’s own immune system recognize and destroy cancer cells. Drugs like checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cell therapy, and cancer vaccines are transforming the outlook for many patients, particularly those with previously untreatable cancers.

Hormone therapy is used in cancers like breast and prostate cancer that are fueled by hormones. Blocking these hormones can slow or stop tumor growth.

Clinical trials offer access to cutting-edge therapies and are an essential part of cancer research. Every drug that becomes standard treatment today once began as a risky experiment tomorrow.

Survivorship and the New Normal

Surviving cancer is not just about living—it’s about learning to live again. For those who reach remission, life doesn’t return to what it was. There are scars, physical and emotional. There may be chronic fatigue, changes in appearance, altered relationships, and ongoing fear of recurrence.

Survivorship is its own phase of cancer care, requiring support, follow-up, and often, rehabilitation. But it also brings resilience. Many survivors report a renewed appreciation for life, stronger relationships, and a sense of purpose forged in the fire of adversity.

For others, cancer becomes a chronic condition—managed but not cured. Advances in treatment have turned some deadly cancers into long-term illnesses. Patients may live for years, even decades, on maintenance therapies.

Palliative care, often misunderstood as end-of-life care, actually plays a crucial role at all stages of cancer. It focuses on improving quality of life, managing symptoms, and supporting mental health. When the end does come, hospice care can offer dignity, peace, and comfort.

The War Is Not Over: Research, Equity, and the Future

Despite remarkable progress, cancer remains a leading cause of death worldwide. It claims millions of lives every year, often disproportionately among the poor, the marginalized, and those without access to quality healthcare. There is a pressing need not just for new treatments, but for better systems—screening programs, education, vaccines, and equitable access to care.

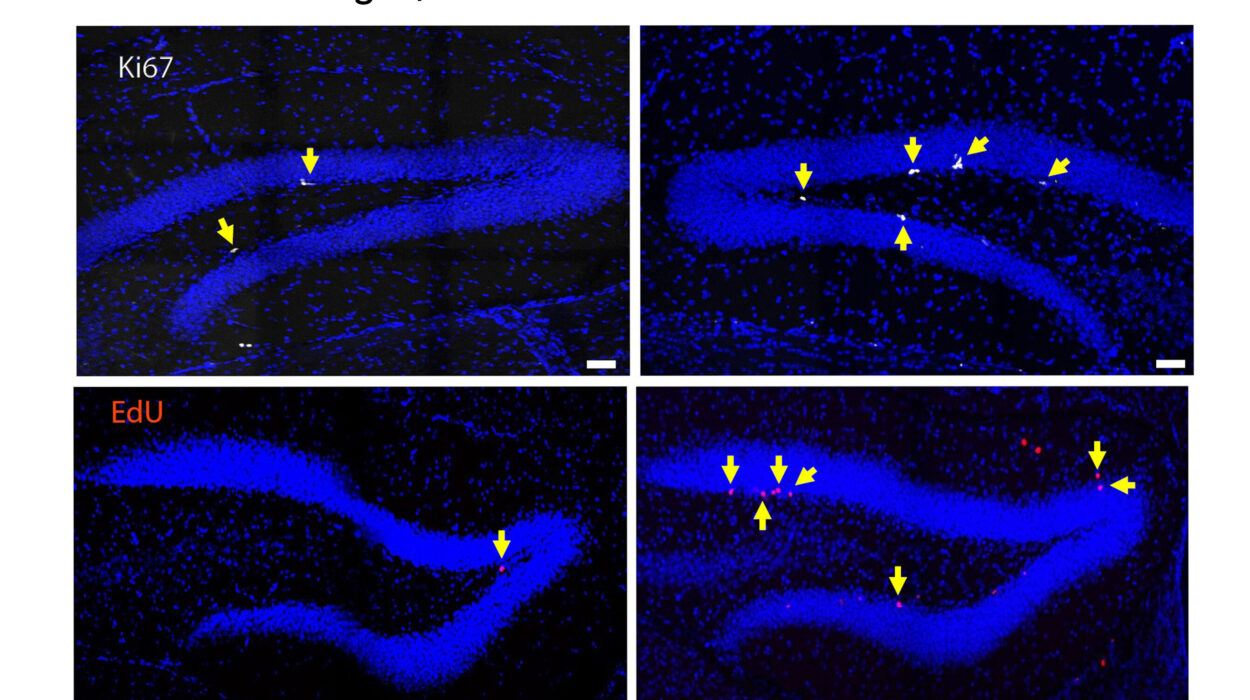

Research is moving rapidly. Scientists are exploring the microbiome, the role of inflammation, gene editing, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence in cancer care. Tumors can now be profiled down to individual cells. Liquid biopsies promise early detection from a simple blood sample. The dream of a universal cancer vaccine is no longer science fiction.

But perhaps the greatest challenge remains understanding the human side of cancer—not just the biology, but the experience. Cancer touches nearly everyone at some point—either directly or through someone they love. It is a medical issue, yes, but also a deeply personal one.

Conclusion: From Fear to Understanding

Cancer will likely always be part of the human story. It is embedded in our biology, a consequence of the very processes that give us life. But how we face it—scientifically, emotionally, and culturally—defines who we are.

To fear cancer is natural. To understand it is empowering. And to fight it is one of the noblest efforts of modern medicine.

Because every time a researcher peers into a microscope, every time a surgeon enters an operating room, every time a patient chooses to fight, rest, hope, or endure—humanity pushes back against the darkness.

Cancer is not just a disease. It is a battleground of science, courage, and love. And the more we learn, the more we illuminate the path forward—not just toward a cure, but toward a world where fewer lives are interrupted by this ancient and relentless foe.