There will come a time when humanity is no longer here. Whether through gradual decline, environmental collapse, nuclear war, artificial intelligence gone awry, pandemics, or the slow ticking of deep time itself, our species—like all others—will vanish. Our cities will crumble. Our machines will rust. Our stories, etched into silicon and ink, will fade beneath the soil. And in the hush that follows, the Earth will continue turning, indifferent, enduring.

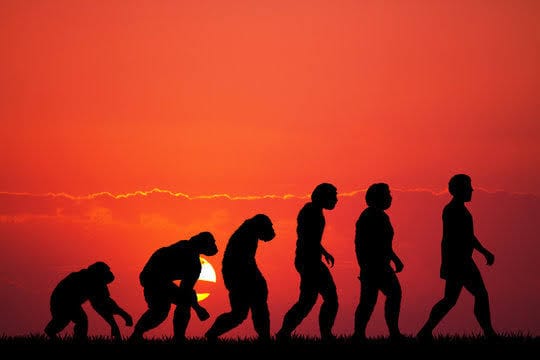

But life will not end with us. The tapestry of evolution is ancient and resilient. It survived the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. It rebounded from ice ages and extinction events. It adapted to volcanic eruptions, shifting continents, and changing skies. After humans are gone, life will keep evolving. The question is not whether something will take our place—but what.

Peering into the evolutionary future is speculative, but not unscientific. We can’t predict the exact creatures that will come after us, but we can follow evolutionary logic, ecological principles, and fossil history to imagine plausible futures. The Earth is a laboratory in perpetual motion, and after we are gone, it will begin new experiments. The animals and plants we leave behind—both wild and domesticated—will be the raw material for tomorrow’s evolutionary revolutions.

The World We Leave Behind

Human extinction won’t reset evolution. It will simply remove a dominant player—us—from the stage. But our influence will linger for millennia. The world post-humanity won’t resemble the world pre-humanity. It will carry our fingerprints, long after we are gone.

The species we drove to extinction will never return. The forests we felled will regrow, but slowly and unevenly. We have changed river courses, drained wetlands, and warmed the planet. We have built roads, cities, and dams that may take centuries or even longer to disappear. Our impact will persist in the form of radioactive isotopes, synthetic chemicals, and domesticated animals that may or may not survive without us.

Cows, dogs, rats, cats, pigs, goats, chickens—creatures we have bred to live among us—may face extinction themselves, or evolve dramatically to fill new ecological roles. Wild animals like raccoons, coyotes, pigeons, and foxes, which have adapted to live alongside us in urban landscapes, may flourish in the ruins of our cities, transforming into entirely new species over time.

Plants, too, will inherit a changed world. Crops engineered for human use may go feral. Weeds, often seen as pests, may become the dominant flora in new ecosystems. Evolution will favor traits that help organisms survive in the post-human world—a world shaped by climate instability, pollution, and the relics of industry.

The Pace and Pulse of Evolution

To imagine the next dominant life forms, we must first understand how evolution works across long timescales. Evolution does not “aim” for complexity or intelligence. It is not a ladder climbing toward progress. It is a branching, messy, creative process of trial and error. Genes mutate. Populations adapt. Environments shift. Those best suited to survive and reproduce do so, and those who don’t, vanish.

Over short timescales—decades or centuries—we might see small shifts: fur colors changing, new diets emerging, or slightly altered behaviors. Over millennia, skeletons might change, limbs might shrink or grow, and sensory systems might evolve. Over millions of years, lineages can diverge dramatically, giving rise to entirely new families, orders, or even phyla.

When humans disappear, evolution won’t stop. It will just accelerate in certain places. Ecological niches will open up. The top predator will be gone. Scavengers will have less competition. Forests and grasslands will rewild. And given time—lots of time—strange and astonishing forms of life will emerge to fill the void we leave behind.

The Rise of the Scavengers and Survivors

The first wave of evolutionary change may come from the survivors—those who endure the collapse of human civilization. If a catastrophic event wipes us out, it’s likely to be one that affects large mammals severely. Throughout evolutionary history, mass extinctions have disproportionately eliminated big-bodied animals, which require more food, reproduce slowly, and have low population densities. Small creatures—rats, beetles, frogs, birds—tend to fare better.

Rats, in particular, are exceptional candidates for evolutionary success. They are highly adaptable, reproduce quickly, and can eat almost anything. In a post-human world, rats could fill the void left by us and other top mammals. Over thousands or millions of years, natural selection could favor larger size, greater intelligence, and new social structures. One could imagine future “rat-people”—rodents that stand on two legs, manipulate objects with dexterous paws, and live in communal burrows.

Crows and ravens, already among the most intelligent non-human animals, might evolve further. With their capacity for tool use, problem-solving, and communication, they could become more cooperative, more manipulative, or more dominant in ecosystems. In a world without humans, their cognitive abilities could be favored by selection, leading to bird species with even more sophisticated behaviors.

Octopuses and other cephalopods, too, present intriguing possibilities. While their lifespans are currently short, preventing the development of culture, natural selection could favor longer-lived individuals, giving rise to more complex social learning. In a future ocean, it’s not entirely implausible that intelligent, social cephalopods could evolve into the dominant form of sentient life.

A Return to the Sea?

Life began in the oceans, and it may return there after our reign. Marine environments are more stable over geologic timescales than terrestrial ones. While the oceans are suffering from overfishing, warming, and acidification, they remain vast and full of life. The deep sea, relatively untouched by human hands, is a crucible for evolutionary innovation.

Whales, dolphins, and seals could diversify into new forms. Without human interference, they may repopulate regions we emptied. Predatory fish like tuna and sharks may reclaim lost niches. Coral reefs, if they survive climate change, could host entirely new ecosystems of bizarre and radiant life.

Over millions of years, it’s conceivable that some land animals may evolve to return to the oceans. Just as mammals like whales and sea cows once did, descendants of raccoons, rodents, or pigs might slowly become aquatic, their limbs turning into flippers, their lungs adapting to hold breath longer, their senses shifting to suit an underwater life.

This aquatic evolution would be slow but dramatic. It could yield creatures that look alien to us—limbless swimmers with sonar, bio-luminescence, or new methods of navigation. Evolution’s toolkit is limitless when given enough time and opportunity.

The Future of Intelligence

Will intelligence evolve again? And if it does, will it resemble ours?

Intelligence, as we define it—language, problem-solving, abstract thought—has evolved only once to our level. This suggests it is not an inevitable endpoint of evolution, but rather an extremely rare convergence of circumstances. However, lesser forms of intelligence are widespread. Many birds, mammals, and cephalopods demonstrate problem-solving, social learning, and even self-awareness.

If intelligence provides a survival advantage in a post-human world—such as in hunting, cooperation, or environmental manipulation—then it may be selected for. Evolution could favor creatures with better memory, communication, and planning. But it might take a different path than ours.

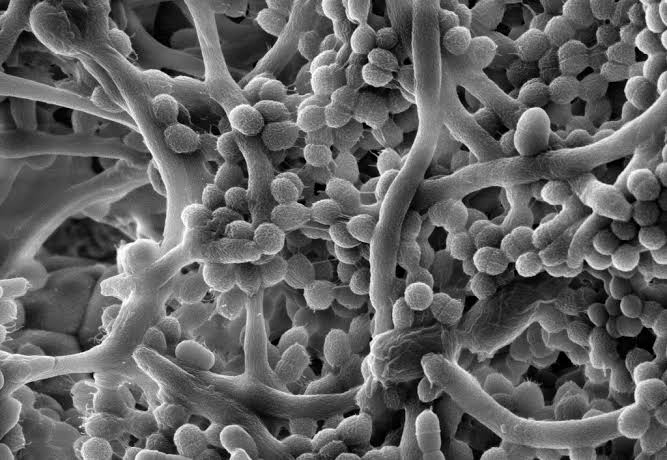

Perhaps a future species will develop sonar-based languages, or pheromone-based communication. Perhaps social insects, like ants or bees, could evolve into superorganisms with shared intelligence spread across colonies. Or perhaps intelligence will emerge in ways we can’t even imagine—in systems of mycelial fungi, in symbiotic collectives, or in deep-sea organisms using electricity or magnetism.

And even if intelligence does arise again, it may never lead to civilization. Intelligence does not guarantee culture, technology, or philosophy. It’s possible that future sentient beings will live in harmony with their world, never needing to build cities or machines. Their intelligence may be spiritual, emotional, or biological rather than mechanical.

The Afterlife of Machines

One of the strangest questions about the post-human world is what happens to our machines. While most will decay, corrode, or be buried, some could outlive us for millennia. Robots, satellites, data servers, and artificial intelligences could remain functional long after we’re gone.

Could machines evolve? Not in the biological sense, but through algorithmic adaptation or self-repair. If artificial intelligences were programmed to survive, replicate, or optimize themselves, they might persist. In a distant scenario, they could become the next dominant “life form”—a silicon-based intelligence built upon the ruins of carbon life.

This speculative future is often the realm of science fiction, but it raises profound questions. If intelligent machines survive us, will they preserve our memory or erase it? Will they replicate human consciousness or create something entirely alien? Will they evolve values or remain cold, computational entities?

Even if AI does not outlive us, the possibility of machine inheritance lingers—a shadow of our ambitions, a final legacy etched in code.

The Beauty of Speculative Evolution

Some scientists and artists have devoted their lives to imagining the life forms of the far future. Speculative biology, though not always rigorous, offers a framework to think creatively about evolution’s potential. It explores how physiology, behavior, and ecosystems might co-evolve under different constraints.

Could flight evolve again from ground-dwelling mammals? Could herbivores develop photosynthetic symbiosis with algae? Could ecosystems arise in radioactive ruins, favoring radiation-resistant species? Could new forms of parasitism, camouflage, or mimicry take over?

In the absence of humans, the great evolutionary canvas is blank once more. Evolution will fill it with color, shape, and motion—guided not by design, but by survival. The results will be breathtaking and often strange: creatures with functions, forms, and features that reflect the pressures of their worlds.

And though we won’t be here to see them, they will be our successors—not in consciousness, but in inheritance. They will live in the world we made, for better or worse.

Echoes of Humanity

If intelligent life does evolve again, it may one day discover traces of us. Fossils of our bones. Tools of our industry. Plastic embedded in rocks. Perhaps even fragments of language or art, preserved in ice, tar, or the deep ocean.

What will they think of us?

Will we be gods to them, fallen and mysterious? Or fools who destroyed themselves with too much knowledge? Will they understand our science, read our stories, mourn our loss?

Or will we be a brief flicker in deep time—another failed experiment in Earth’s evolutionary journey?

Our true legacy may not be what we built, but what we enabled: the continued flowering of life. The resilience of biology. The endless dance of evolution.

And perhaps, somewhere in the vastness of tomorrow, a new creature will look at the stars, as we once did, and wonder: who came before us?

The Living Future

Evolution after humanity will not stop. It will not mourn us. It will not miss our monuments or music. But it will carry on the song of life in new verses and keys.

Forests will reclaim cities. Rivers will change course. Animals will adapt, migrate, speciate. The Earth will live, grow, and change, just as it always has.

And though we may vanish, we are not erased. We are part of the fossil record, part of the genetic web, part of the evolutionary tree. Life will continue—wild, weird, and wondrous.

It always has.

It always will.