Deep in the dense, humid rainforests of Guinea-Bissau, where sunlight filters through thick canopies and the jungle hums with hidden life, a new kind of music has emerged—played not by humans, but by our closest evolutionary relatives. Adult male chimpanzees have been observed rhythmically striking stones against trees, producing resonant, drum-like sounds that echo through the undergrowth.

At first glance, this might seem like just another display of primate playfulness. But to a team of behavioral biologists from Wageningen University & Research and the German Primate Research Center, these sonic rituals hint at something far more profound: a form of communication, passed down through generations, embedded in chimpanzee culture.

Over five years, scientists painstakingly documented this phenomenon using camera traps placed at five remote locations inside a protected nature reserve. What they found was both mysterious and mesmerizing: chimps—notably adult males—engaging in what researchers have dubbed “stone-assisted drumming,” repeatedly slamming rocks into tree trunks with deliberate force. As these behaviors continued, the forest floor beneath favored trees began to accumulate curious piles of stone—the tangible evidence of what may be the first known instance of tool-assisted acoustic signaling in wild chimpanzees.

From Pant-Hoots to Percussion

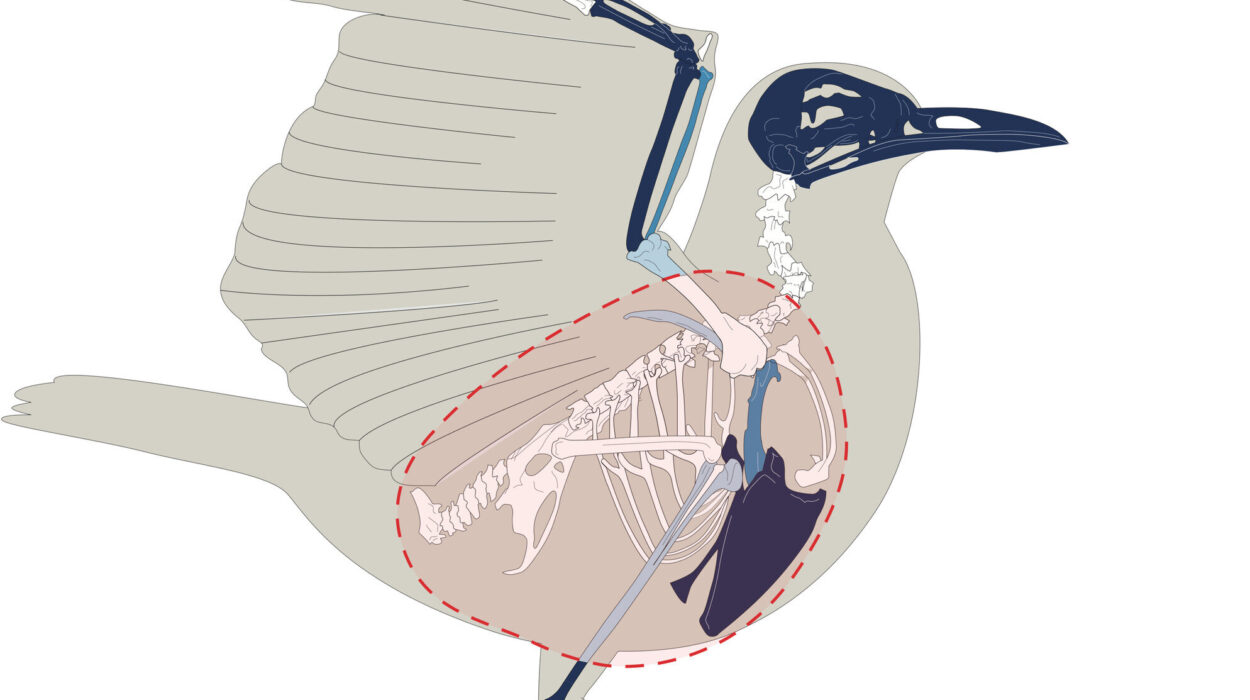

Dr. Sem van Loon, the study’s lead author, describes the behavior as potentially analogous to the better-known “buttress drumming” common among chimpanzee groups across Africa. In that classic display, chimps drum with their hands or feet on the hollow roots of large trees, creating low-frequency sounds that travel across long distances. These vocal and physical displays often serve to broadcast dominance, coordinate group movement, or reinforce social bonds.

But stone-assisted drumming is different. Van Loon and her colleagues noticed that before picking up and hurling stones, the chimps frequently let out loud pant-hoots—exuberant, rising calls that carry through the trees—followed by an eerie silence before the stone strikes. This sequencing is the inverse of traditional drumming behavior, where vocalization typically follows or accompanies the percussion.

Why the switch in order? The answer may lie in the sound itself. “The acoustic properties of a stone striking a tree differ significantly from bare-handed drumming,” Van Loon notes. “The resulting sound is deeper, sharper, and likely travels farther—especially useful in the acoustically cluttered environment of dense forest.”

In short, chimps may be innovating a new communication channel, one that exploits the natural physics of sound to cut through the jungle noise more effectively than traditional methods.

More Than a Sound: Signs of Culture

Perhaps even more compelling than the behavior itself is how it spreads. Stone-assisted drumming is not universal among chimpanzees. It appears only in specific regions of Guinea-Bissau, and even within those areas, not every group engages in it. This patchy distribution strongly suggests cultural learning rather than genetic inheritance.

Young chimpanzees appear to pick up the behavior by observing older males—mimicking the technique, refining it, and eventually performing it independently. It is not instinctual; it is taught. And this revelation turns a new page in the growing body of evidence that chimpanzees, like humans, have culture.

Marc Naguib, a professor of Behavioral Ecology and co-author of the study, emphasizes the significance: “This discovery underscores the fact that culture is not a human monopoly. Chimpanzees, too, possess the ability to learn, imitate, and transmit complex behaviors across generations.”

In the past, chimpanzees have astounded scientists with their ingenuity—from crafting fishing sticks to extract termites, to using leaves as drinking sponges or spears for hunting small mammals. But stone-assisted drumming stands out because it appears to serve no direct material purpose. It’s not about food. It’s about expression—or perhaps, communication. That makes it strikingly similar to the origins of human music or ritual.

Sound Carved in Stone

The discovery opens a window into not only chimpanzee minds, but possibly our own distant past. Anthropologists have long speculated about how early hominins used sound, tools, and the environment to communicate. Could our own ancestors have started their path toward language, music, or ritual by similarly striking objects to produce rhythm?

The piles of stones left behind by the chimps are particularly provocative. These accumulations echo ancient human practices—like the cairns and rock piles found in archaeological sites from early human settlements. Are these chimpanzee stone mounds merely incidental, or could they signify something more—a marker of place, a performance stage, or even a primitive form of symbolism?

While the idea of chimpanzees creating proto-shrines or altars may sound speculative, the field of primate archaeology is beginning to entertain such questions with increasing seriousness. After all, symbolic behavior doesn’t require speech—it requires memory, intention, and shared understanding. All qualities chimps have repeatedly demonstrated.

Conservation Implications: Culture Worth Protecting

Beyond the scientific excitement, the findings carry important messages for conservation. If chimpanzees possess localized cultures—unique traditions that may not exist elsewhere—then the destruction of their habitats is not just a loss of animals, but a loss of knowledge, of history, of identity.

In other words, when a forest falls, it may not just silence the cries of its inhabitants, but also erase their songs.

“This behavior illustrates that protecting biodiversity must go hand-in-hand with protecting behavioral diversity,” Naguib states. “Conservation strategies must account for not just species, but the cultural worlds those species inhabit.”

The nature reserve in Guinea-Bissau, where this study was conducted, remains one of the few protected enclaves of such chimpanzee culture. The support of local field guides was essential—not only for logistics, but also for contextual understanding. Their traditional ecological knowledge helped identify chimpanzee trails, understand local animal behavior, and contextualize the findings within the broader landscape.

What Comes Next?

Like the first listeners of a strange new melody, researchers are now grappling with a blend of excitement and questions. What exactly do these stone sounds communicate? Are they signals of territory, dominance, or emotional state? Might they be used to summon allies, deter rivals, or simply to feel the power of sound resonate through the forest?

Future studies aim to deploy directional microphones and acoustic analysis to map the sonic profiles of these strikes and how they travel through forest environments. Ethologists hope to determine whether individual chimps have unique “drumming signatures,” akin to the way some birds have distinct calls. There is also interest in examining whether females or juveniles eventually adopt this behavior under different social circumstances.

Van Loon and her team remain cautious but hopeful. “Every new behavior we observe opens another door into the emotional and cognitive lives of these animals,” she reflects. “Stone-assisted drumming may be the beginning of a new understanding, not only of chimpanzee communication but of the evolutionary roots of our own sonic culture.”

A Symphony of the Wild

In the forested silence after a pant-hoot, when a stone strikes wood and echoes into the canopy, something ancient stirs. Perhaps it’s memory, perhaps it’s instinct. Perhaps it’s simply the sound of another intelligent being declaring its presence in a vast and echoing world.

Whatever it is, the chimps of Guinea-Bissau are drumming a message across time and species boundaries. And for those willing to listen, it’s a rhythm worth decoding—not only for what it tells us about them, but for what it might remind us about ourselves.

Reference: Sem van Loon et al, Stone-assisted drumming in Western chimpanzees and its implications for communication and cultural transmission, Biology Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2025.0053