In a groundbreaking study published in Neuropharmacology, researchers have discovered that very low doses of a psychedelic drug known as DOPR (2,5-Dimethoxy-4-propylamphetamine) significantly increased motivation in mice that initially showed low drive. Remarkably, this boost in motivation came without the usual hallucinogenic side effects commonly associated with psychedelic compounds. These findings offer a tantalizing glimpse into a new approach for treating psychiatric conditions like depression—by precisely targeting motivational deficits without altering consciousness.

The Silent Struggle of Amotivation

Amotivation, the loss of initiative to seek rewards or pursue goals, is a deeply disabling feature of many mental health disorders, including major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizophrenia. While antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are frontline treatments, they often fall short in addressing this crucial symptom. SSRIs can take weeks to begin working, and even then, many patients continue to suffer from a lack of drive and emotional numbness.

Newer interventions like ketamine have drawn attention for their fast-acting properties, but they bring their own baggage—possible dissociation, dependency concerns, and the need for medical supervision. As such, scientists have been on the hunt for treatments that are both effective and easier to tolerate. This is where psychedelics have entered the picture—but with a twist.

The Promise and Problem of Psychedelics

Psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD have shown impressive results in clinical trials for depression, often delivering relief within hours or days. However, these compounds induce powerful hallucinations and altered states of consciousness. That means they must be administered in a controlled, clinical setting with careful monitoring—posing a barrier to widespread therapeutic use.

Enter “microdosing”—the practice of taking sub-perceptual doses of psychedelics that are too low to cause hallucinations but may still influence mood, cognition, and behavior. Anecdotal reports have long claimed that microdosing enhances creativity, focus, and even emotional resilience. Yet until recently, scientific evidence supporting these claims has been scant.

This new study takes a crucial step forward by providing empirical data that microdoses of a psychedelic can selectively enhance motivation in subjects suffering from low baseline drive, without tripping the psychedelic “wires” in the brain.

DOPR and the Motivation Circuit

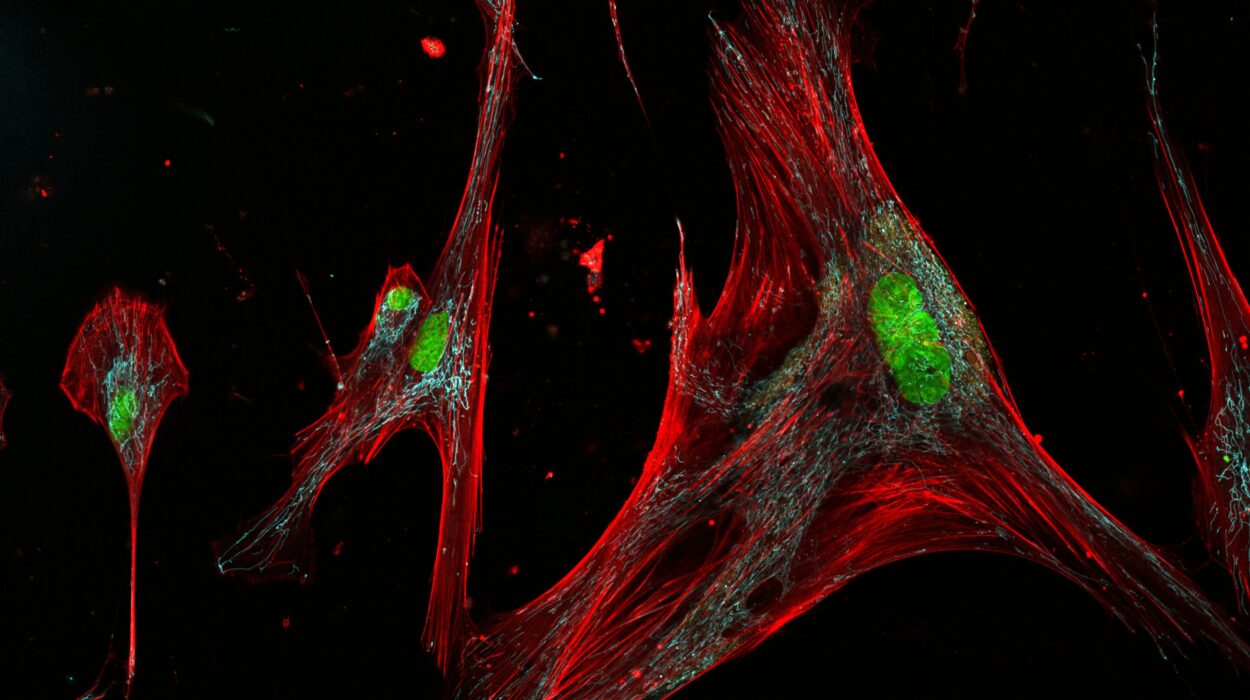

The study focused on DOPR, a synthetic psychedelic compound in the phenethylamine class, structurally related to mescaline. Like other classic psychedelics, DOPR activates the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor, which is widely implicated in the mechanism of action for hallucinogens. But the researchers wanted to know whether DOPR could enhance motivation without triggering those intense subjective experiences.

To test this, scientists at a major research university conducted a detailed behavioral experiment using mice. They relied on a well-established metric called the progressive ratio breakpoint task (PRBT). In this task, mice had to perform an increasing number of nosepokes to receive a sweet treat. The highest number of efforts a mouse was willing to make before giving up—its “breakpoint”—was used as a measure of motivation.

Study Design: Precision Over Power

The researchers tested 80 mice, evenly split by sex, using a within-subject design to minimize variability. Each mouse was given several doses of DOPR—ranging from 0.0106 mg/kg to 0.32 mg/kg—across different sessions. For comparison, the team also administered amphetamine, a well-known stimulant with established motivation-enhancing effects.

To determine whether DOPR caused hallucinogenic-like activity, the scientists used a separate test involving the head twitch response (HTR)—a rodent behavior that reliably predicts whether a drug produces hallucinations in humans.

Key Findings: Targeted Boosts Without Trippy Side Effects

The results were both intriguing and promising. Mice that started with low motivation—the ones with the lowest breakpoints in the PRBT—showed significantly increased effort after receiving low doses of DOPR. The most pronounced improvements were observed at doses of 0.0106, 0.106, and 0.32 mg/kg. In contrast, mice that were already highly motivated showed no change, indicating that the effect was selective rather than universal.

This dose-dependent and state-dependent response was strikingly similar to that seen with amphetamine, suggesting that DOPR acts specifically on neural circuits related to effort and goal-directed behavior.

Most importantly, the lowest dose of DOPR that increased motivation (0.0106 mg/kg) did not trigger an increase in head twitch responses. That means the drug was able to enhance behavioral drive without activating the psychedelic experience, at least as inferred from animal models.

A Closer Look at DOPR’s Mechanism

The researchers also delved into the pharmacology of DOPR, analyzing how it interacts with different serotonin receptors. They found that DOPR is a strong agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor—the same receptor targeted by psilocybin and LSD—but shows much weaker activity at other serotonin subtypes, such as 5-HT1A.

This receptor selectivity is crucial. It suggests that DOPR can “tune” the brain’s serotonin system in a more targeted way, potentially isolating therapeutic benefits from the more disruptive aspects of psychedelics. That fine-grained control could mark a turning point in designing drugs that improve mood and motivation without the need for full-blown psychedelic experiences.

A Glimpse Into the Future of Mental Health Treatment

What does this mean for real-world applications? The findings hint at a new class of treatments that could be especially helpful for individuals with depression, schizophrenia, or other disorders where amotivation plays a central role. By administering psychedelic compounds in microdoses, it might be possible to restore the brain’s reward-seeking circuits without triggering the perceptual shifts and hallucinations that require clinical oversight.

Such treatments could be safer, faster-acting, and more accessible than current options, offering hope to millions who struggle with motivation-related symptoms.

Caveats and the Road Ahead

Despite its promise, the study is not without limitations. The mice were not subjected to full models of depression, such as chronic stress or inflammatory paradigms. Instead, they were simply categorized as “low” or “high” performers based on their behavior in a single task. That means the findings might not fully generalize to human patients with complex psychiatric conditions.

Additionally, while DOPR’s action on the 5-HT2A receptor is well characterized, its influence on other serotonin receptors—particularly 5-HT2C—remains less clear. This is important because 5-HT2C is involved in regulating appetite and motivation, and previous research has shown that selectively activating this receptor can actually reduce motivation. Further studies are needed to untangle the precise contributions of each receptor subtype.

There’s also the challenge of translating findings from rodent models to human brains. While the head twitch response is a reliable predictor of psychedelic effects, it’s not a perfect match for the complex experience of a human trip. Human trials will be essential to confirm whether these low doses truly avoid perceptual side effects in people.

Microdosing: Science or Hype?

For years, microdosing has been championed in pop culture and Silicon Valley as a cognitive enhancer. But only recently have scientific studies started to catch up. This research represents a significant step in validating microdosing as a potential therapeutic tool—one that can be fine-tuned to deliver benefits while minimizing risks.

Still, it’s important to remain cautious. The placebo effect is powerful, and some studies have found that perceived benefits of microdosing in humans may not hold up under rigorous double-blind conditions. That’s why controlled, well-designed trials like this one are so vital—they help separate fact from fiction.

The Psychedelic Renaissance: A Tidal Shift in Psychiatry

This study is part of a broader movement known as the psychedelic renaissance—a resurgence of interest in using hallucinogenic compounds for mental health. From psilocybin-assisted therapy for end-of-life anxiety to MDMA for PTSD, the field is exploding with possibility.

But the holy grail has always been to capture the therapeutic essence of these substances without the baggage. If compounds like DOPR can reliably enhance motivation in vulnerable populations without inducing hallucinations, it could revolutionize how we treat depression and related conditions.

Conclusion: New Tools for an Age-Old Struggle

Motivation is the invisible engine behind everything we do—our ambitions, our resilience, our recovery. For those whose engines have stalled due to mental illness, traditional treatments often fall short. The discovery that low doses of psychedelics like DOPR can jumpstart this engine without the complications of a “trip” is a major breakthrough.

As research continues, we may find ourselves on the cusp of a new era in psychiatry—one where healing doesn’t require hallucination, and where a tiny dose of insight can go a long way.