As the sun dips below the horizon, millions of rods in our retinas awaken to capture the faintest glimmers of twilight. But for those living with retinitis pigmentosa—a genetic disease that slowly steals night vision before plunging its victims into darkness—those rods become silent, one by one, like stars winking out in a clouded sky.

Yet deep within the eye, a surprising story of resilience is unfolding.

Scientists at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA have discovered that when vision begins to deteriorate, certain retinal cells don’t simply surrender. Instead, they rewire themselves, forging new connections in a desperate, yet astonishing, bid to keep the world visible.

Their findings, published in the journal Current Biology, hint at hidden networks of adaptability within the eye—offering fresh hope for treatments to preserve vision in millions threatened by inherited blindness.

The Retina’s Secret Backup Plan

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is no ordinary disease. It’s a slow-motion tragedy, creeping in over years or decades. Mutations in genes like rhodopsin cripple the retina’s rod cells—the light-sensitive sentinels responsible for night vision and peripheral sight. As rods die off, people lose the ability to navigate dark rooms, recognize faces in low light, or drive at night. Eventually, the loss encroaches on daylight vision, bringing the world into a permanent dusk.

But scientists have long wondered: does the retina simply fall silent as rods vanish? Or does it try, in its own quiet way, to adapt?

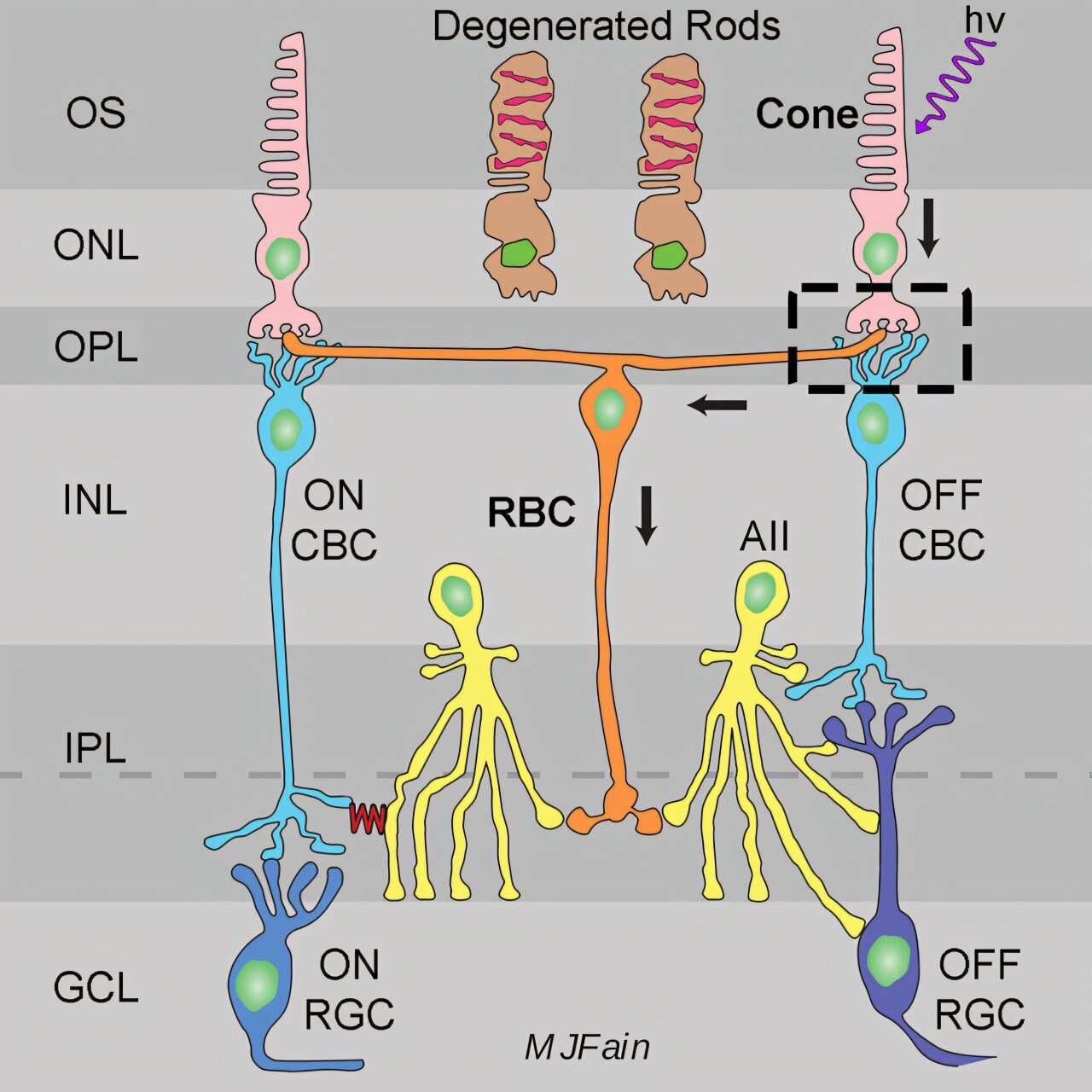

At UCLA, Dr. A.P. Sampath and colleagues set out to trace that mystery to its roots. Using genetically engineered mice that model early-stage RP, the team zoomed in on a crucial type of neuron called rod bipolar cells.

“These cells are like loyal partners to rods,” Sampath explained. “Under normal conditions, they receive signals from rods and help relay visual information deeper into the brain. But when rods die, we didn’t know what happened to the bipolar cells. Did they wither away? Or find new dance partners?”

New Connections Born from Loss

Through delicate experiments, the researchers recorded tiny electrical signals from individual rod bipolar cells in mice whose rods could no longer respond to light. What they found was both unexpected and beautiful.

Instead of sitting idle, rod bipolar cells had learned a new language: they began picking up signals from the retina’s cones—the cells responsible for daylight and color vision.

“In these animals, the rod bipolar cells showed large, robust electrical responses driven by cones, rather than their normal rod inputs,” Sampath said. “It’s as if they switched allegiances to keep the visual system running.”

This rewiring wasn’t random. The cone-driven signals matched the electrical fingerprints scientists expected. The rod bipolar cells weren’t just receiving static; they were meaningfully processing cone input—an entirely new pathway forged in the midst of degeneration.

Why Degeneration Sparks Change

The team probed deeper to find out what triggers this remarkable plasticity. They examined mice with other kinds of rod defects—animals whose rods were silent due to faulty proteins, but who hadn’t experienced rod cell death. In those mice, the rod bipolar cells did not rewire to cones.

This crucial detail suggests that it’s not simply the absence of rod signals that drives bipolar cells to change their connections. Instead, it’s the process of degeneration itself—the dying off of rod cells—that sends out molecular distress calls.

“The signal for this plasticity appears to be degeneration itself,” Sampath said. “It could involve glial support cells or factors released by dying rods. The retina seems to recognize that something catastrophic is happening and tries to compensate.”

A Resilient Retina—and New Hope

The discovery builds on the UCLA team’s earlier work from 2023, which showed that individual cones can keep functioning even after significant structural damage in later stages of retinal disease. Together, these findings paint a hopeful picture: the retina isn’t passive in disease—it fights back.

Understanding these natural rewiring mechanisms opens tantalizing new avenues for therapy. If scientists can harness or enhance these adaptive changes, they might develop treatments to preserve or even restore vision for patients facing retinal degeneration.

“It shows us that the retina is more flexible than we thought,” Sampath said. “There may be ways to guide or boost these rewiring processes to help people maintain sight longer.”

Questions Yet to Answer

The research also raises new questions. Is this rewiring unique to specific genetic forms of RP? Does it happen in humans as it does in mice? And can these new connections sustain meaningful vision, or might they eventually lead to garbled signals and further complications?

The UCLA team is already exploring other mouse models with different rhodopsin mutations to find out whether this adaptability is a universal response in the retina.

For patients and families living under the shadow of retinitis pigmentosa, even small glimmers of hope are precious. In the delicate layers of the retina, nature may have hidden an unexpected lifeline—a story not just of vision lost, but of neurons that refuse to give up.

In the quiet darkness of the eye, a revolution is unfolding. And it’s reminding scientists—and all of us—that even in blindness, the human body is still fighting to see.

Reference: Paul J. Bonezzi et al, Photoreceptor degeneration induces homeostatic rewiring of rod bipolar cells, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.057