In 2022 and 2023, more than 1.5 million Americans vanished—not into thin air, not into war or migration, but into graves that did not need to be filled. These were the “missing Americans,” a haunting term coined by researchers to describe the lives that should not have ended when they did. According to a groundbreaking study led by the Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), these deaths would have been avoided if the United States had mortality rates comparable to those of other wealthy nations.

The numbers are staggering. In 2023 alone, more than 700,000 excess deaths occurred—lives that could have continued in a more equitable world. These aren’t just statistical artifacts; they’re mothers, brothers, friends, neighbors—entire human stories cut short in a country that spends more on health care than any other.

This isn’t a new crisis. It’s a decades-long unraveling of American public health, one that has accelerated through years of policy inaction, systemic neglect, and social fracture. COVID-19 threw it into sharp relief, but the story began long before and continues beyond the pandemic’s peak.

An Unfolding Catastrophe Decades in the Making

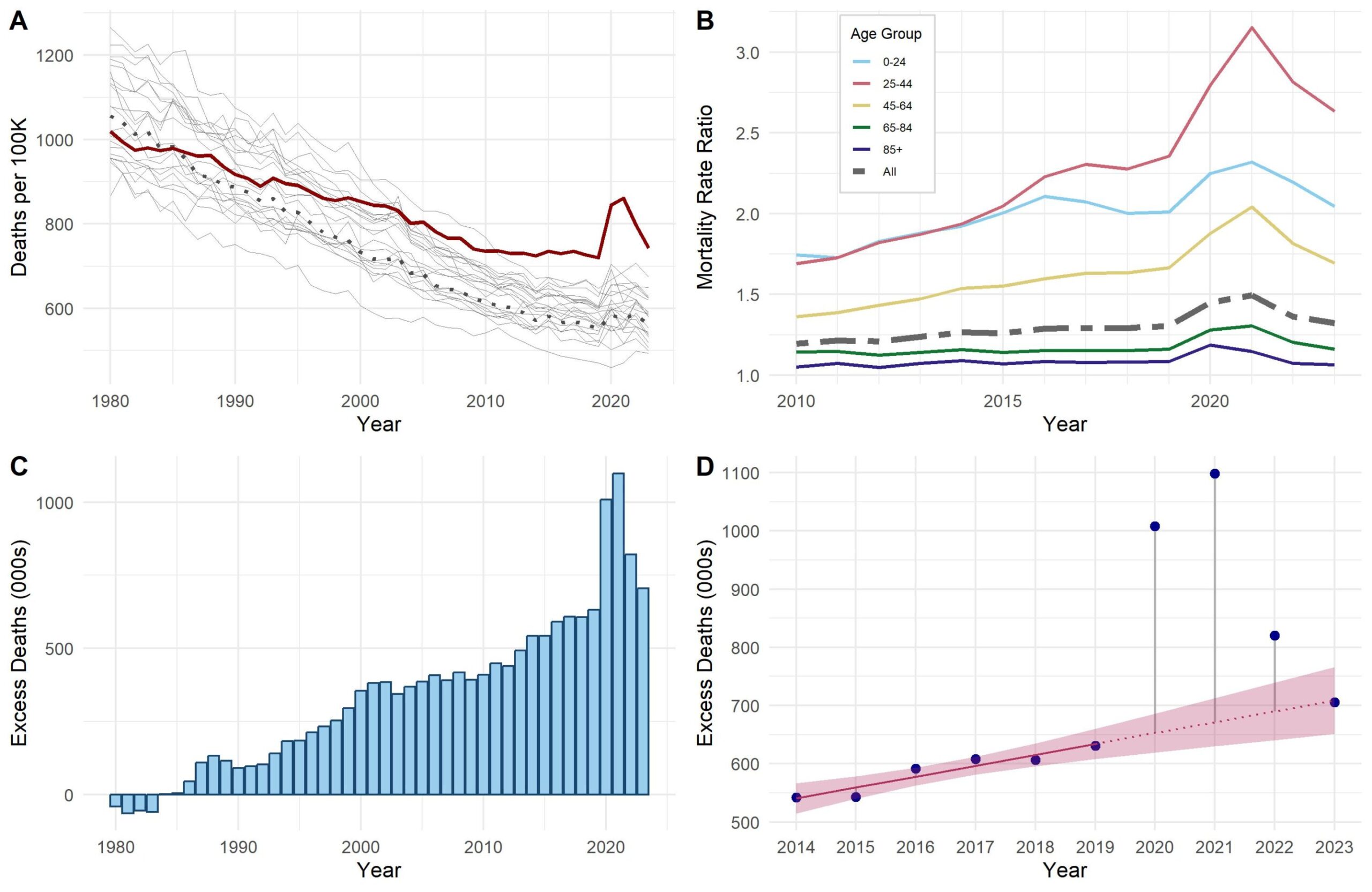

The American health crisis didn’t arrive with the coronavirus—it has been evolving for over 40 years. Researchers analyzed mortality trends from 1980 to 2023 and compared them with those in 21 other high-income nations, including Australia, Canada, France, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The conclusion was irrefutable: the U.S. has been systematically falling behind.

Since 1980, there have been approximately 14.7 million more deaths in the U.S. than there would have been if the nation had mortality rates comparable to its peers. That figure doesn’t just reflect epidemics or medical failures—it is an indictment of structural inequity, fragmented healthcare, and a society struggling to protect its most vulnerable.

The pandemic only widened the chasm. In 2021, at the height of COVID-19, the U.S. recorded over 1 million excess deaths. That number decreased in 2022 and 2023, but remained catastrophically high: 820,396 and 705,331, respectively. Even in 2023, with the acute phase of the pandemic behind us, mortality rates were worse than those in 2019.

These statistics challenge the comforting notion that the worst is over. In truth, the pandemic merely amplified a slow-burning national emergency.

Deaths of Despair—and Policy

What makes these excess deaths especially tragic is their preventability. The driving forces behind America’s abnormally high death rates aren’t rare diseases or uncontrollable disasters—they are largely the result of preventable conditions and societal dysfunction.

Gun violence. Drug overdoses. Car crashes. Cardiometabolic conditions like diabetes and heart disease. These are not fates met randomly; they are consequences of infrastructure, policy, and social context.

As Dr. Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota and co-author of the study, points out: “These deaths are driven by long-running crises.” They are the result of deep-rooted problems in how the U.S. supports—or fails to support—its citizens, especially the working-age population.

In 2023, 46% of all U.S. deaths among people under 65 were “excess”—meaning nearly one in every two deaths among the working-age population might not have occurred had America matched the age-specific mortality rates of its global peers. This is not a pandemic phenomenon. This is an American phenomenon.

The Young Are Dying Younger

Perhaps the most damning aspect of this crisis is who is dying. Unlike in many other countries, where excess deaths are concentrated among the elderly, in the United States, younger adults bear the brunt.

The majority of “missing Americans” are under 65. In 2023, half of all U.S. deaths in this age group could have been avoided with better policy and healthcare infrastructure. These are people in their prime—raising children, building careers, contributing to society.

The reasons are as complex as they are devastating. The opioid epidemic continues to ravage communities. Gun deaths, both homicides and suicides, claim tens of thousands annually. Car accidents, especially in rural and under-resourced areas, remain a top killer. Poor access to primary care and preventive health services leads to uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic conditions. Mental health support is patchy at best, absent at worst.

Dr. Andrew Stokes, senior author of the study and an associate professor at BUSPH, connects these dots clearly: “These deaths reflect not individual choices, but policy neglect and deep-rooted social and health system failures.”

A Nation Adrift from Its Peers

So why is the United States—wealthy, innovative, medically advanced—so far behind? The answer lies not in science but in governance, ideology, and inequality.

In peer nations, universal healthcare ensures that cost is not a barrier to essential care. Social safety nets provide food, housing, and income support during times of crisis. Evidence-based public health policies, from gun regulation to drug treatment programs, are implemented on the basis of data, not ideology.

The U.S., by contrast, spends more per capita on healthcare than any other country but leaves millions uninsured or underinsured. Political gridlock, mistrust of government, and culture wars have made basic public health measures—like vaccination, mask-wearing, or addiction support—points of division rather than unity.

Even as COVID-19 exposed the brittleness of American health infrastructure, the policy response has been uneven. Temporary expansions of Medicaid and food assistance programs helped cushion the blow for some, but many of those protections have since been rolled back.

“Imagine the lives saved,” says Dr. Jacob Bor, the study’s lead author, “if the U.S. simply performed at the average of our peers.” His voice carries a tone of moral urgency. “One out of every two U.S. deaths under 65 is likely avoidable. Our failure to address this is a national scandal.”

Political Headwinds, Uncertain Futures

As the 2020s progress, the health of the American people remains vulnerable to more than viruses. The policies enacted—or dismantled—by future administrations could determine whether this trend is reversed or intensified.

Already, researchers warn that sweeping changes under recent political leadership threaten to erode public health infrastructure further. Proposed cuts to scientific research, environmental regulation, safety net programs, and health data systems could stall progress or even push mortality trends in the wrong direction.

Public health is not just about hospitals and vaccines—it is about food security, clean air, safe streets, and economic opportunity. These are the foundations of health that cannot be separated from politics.

As Dr. Stokes notes, “Other countries show that investing in universal health care, strong safety nets, and evidence-based public health policies leads to longer, healthier lives.” In the U.S., such investments remain politically fraught, hindered by polarization and cultural resistance to collective solutions.

A Path Forward?

There is no silver bullet. But there is precedent. Other nations have succeeded in reducing premature mortality through sustained investment, rigorous data collection, and policies that place public welfare above partisanship. The U.S. has the knowledge, the resources, and the technology—it simply lacks the political will and cultural cohesion.

If the country chooses to act, it can change course. Expanding access to affordable healthcare, strengthening addiction and mental health services, enforcing evidence-based gun control laws, and investing in transportation safety are just some of the proven strategies. But none of them will work in isolation. Only a coordinated, compassionate approach—one that sees health as a social good, not a personal burden—can truly stem the tide.

The tragedy of the missing Americans is not that they are gone. It is that they never had to be. Their absence is a mirror held up to the nation’s priorities. The question now is whether the U.S. will continue down this path—or finally decide that every American life, regardless of age or income, deserves not only to be mourned, but to be saved.

Reference: Excess Deaths Before, During, and After the COVID-19 Pandemic, JAMA Health Forum (2025). DOI: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2025.1118