Fibromyalgia is often described as an “invisible illness.” To those on the outside, it may not leave visible scars, wounds, or markers of disease. But to those living with it, fibromyalgia can be an all-consuming condition—chronic pain, relentless fatigue, and a fog that clouds even the simplest of thoughts. It is a disorder that challenges both the body and the mind, blurring the boundaries between physical and psychological health, and forcing patients to navigate a world that sometimes struggles to recognize their suffering.

Though once misunderstood and dismissed as “all in the head,” fibromyalgia has emerged in modern medicine as a legitimate and complex neurological condition. It affects millions of people worldwide, predominantly women, though men and even children can be impacted. It is not rare, and yet it is often hidden. To truly understand fibromyalgia is to dive into its causes, symptoms, challenges in diagnosis, and evolving approaches to treatment.

What is Fibromyalgia?

Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, cognitive difficulties, and heightened sensitivity to touch and pressure. Unlike arthritis, fibromyalgia does not cause inflammation or damage to joints and tissues. Instead, it seems to involve changes in how the brain and spinal cord process pain signals, amplifying sensations that might otherwise be perceived as minor discomfort.

The word “fibromyalgia” itself is rooted in Latin and Greek: “fibro” (fibrous tissues), “myo” (muscle), and “algia” (pain). Together, they capture the central feature of this disorder—pain that appears to originate in muscles and soft tissues, though its true origins lie in the nervous system.

The Mysterious Causes of Fibromyalgia

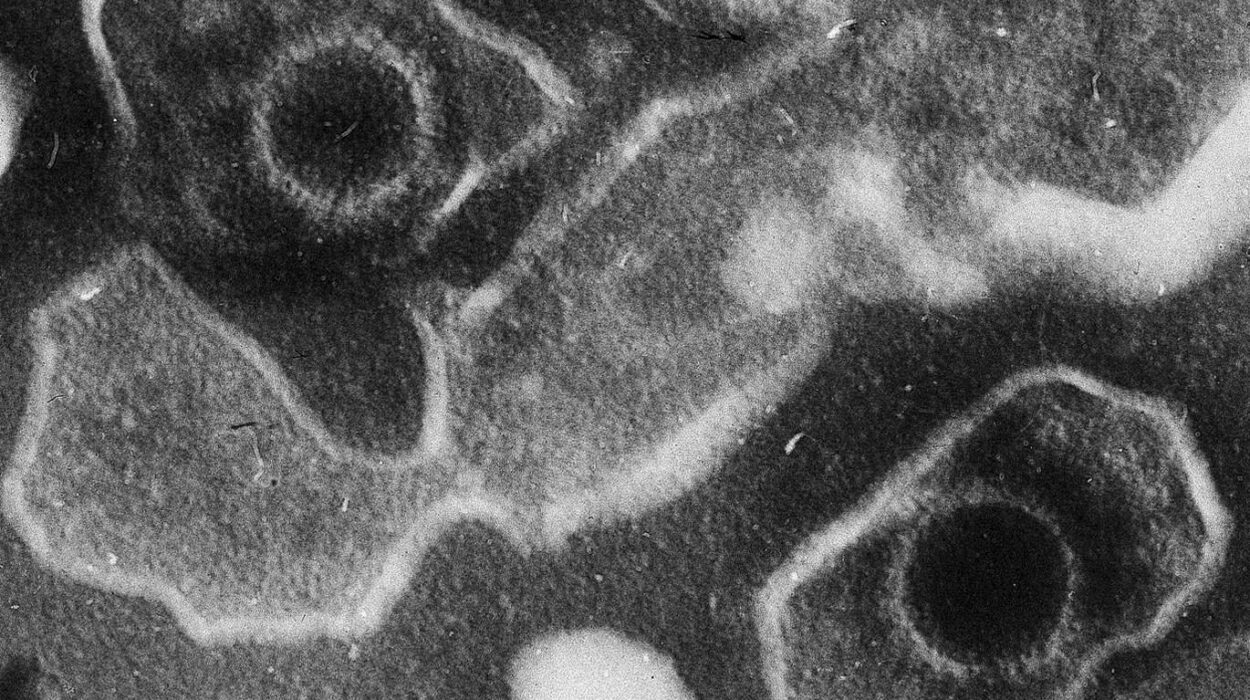

Despite decades of research, fibromyalgia does not have one single identifiable cause. Instead, it appears to result from a combination of genetic, neurological, psychological, and environmental factors. Scientists now view it as a disorder of central pain processing—sometimes described as “central sensitization.”

Genetic Factors

Research has shown that fibromyalgia tends to run in families. People with a parent or sibling who has fibromyalgia are more likely to develop the condition themselves. Specific genetic variations in neurotransmitters—such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—appear to affect how the brain interprets pain signals. These variations may lower the threshold for pain perception, making everyday sensations feel more intense.

Abnormal Pain Processing

In healthy individuals, the brain filters and dampens pain signals to keep them tolerable. In fibromyalgia, however, the nervous system seems to amplify these signals. Functional MRI studies have shown heightened activity in areas of the brain involved in pain perception, even in response to mild stimuli. Neurochemical imbalances, particularly lower levels of serotonin and abnormal amounts of substance P (a neurotransmitter involved in pain transmission), contribute to this heightened sensitivity.

Trauma and Stress

For many patients, fibromyalgia symptoms appear after a physically or emotionally traumatic event. Car accidents, surgeries, infections, or prolonged psychological stress have all been linked to the onset of fibromyalgia. Chronic stress seems to disrupt the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s central stress response system, which in turn alters hormone regulation, sleep, and immune function.

Sleep Disturbances

Poor sleep is both a symptom and a cause of fibromyalgia. People with the condition often do not experience restorative deep sleep, leaving them fatigued and more sensitive to pain. Laboratory studies confirm that interrupting deep sleep in healthy individuals can trigger fibromyalgia-like symptoms, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between poor sleep and chronic pain.

Infections and Immune System Involvement

Certain infections—such as Epstein-Barr virus, Lyme disease, or hepatitis C—have been associated with the onset of fibromyalgia. While not a direct cause, these infections may trigger immune system changes that contribute to the disorder. Some researchers suggest that fibromyalgia shares features with autoimmune diseases, though it is not classified as one.

Psychological Factors

While fibromyalgia is not a purely psychological condition, mental health does play a role. Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more common in patients with fibromyalgia and may exacerbate symptoms. The relationship is complex—fibromyalgia can worsen mental health, and poor mental health can amplify fibromyalgia symptoms.

The Complex Symptoms of Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is not defined by one single symptom but by a constellation of them, varying in intensity from day to day.

Widespread Pain

The hallmark of fibromyalgia is chronic, widespread pain that affects both sides of the body, above and below the waist, and persists for at least three months. Patients often describe the pain as a deep ache, burning, stabbing, or throbbing. What makes it unique is its persistence and unpredictability—pain can shift from one area of the body to another without warning.

Fatigue and Exhaustion

Fibromyalgia is often accompanied by a profound fatigue that does not improve with rest. Patients may feel drained after even minor physical or mental exertion. This fatigue is not simply tiredness but a deep exhaustion that can disrupt work, social life, and basic daily functioning.

Fibro Fog

One of the most frustrating symptoms is “fibro fog”—a collection of cognitive difficulties including poor memory, lack of concentration, confusion, and slowed thinking. It can make everyday tasks such as following conversations, remembering appointments, or focusing at work extraordinarily challenging.

Sleep Disturbances

Many individuals with fibromyalgia struggle with insomnia, restless leg syndrome, or non-restorative sleep. Even after a full night in bed, they may wake up feeling unrefreshed, as though sleep has provided no relief.

Sensory Sensitivities

Fibromyalgia often heightens sensitivity to stimuli beyond pain. Patients may become unusually sensitive to light, sound, smells, and even temperature changes. This hypersensitivity can make ordinary environments overwhelming.

Additional Symptoms

Fibromyalgia is often accompanied by a range of secondary symptoms, including:

- Headaches or migraines

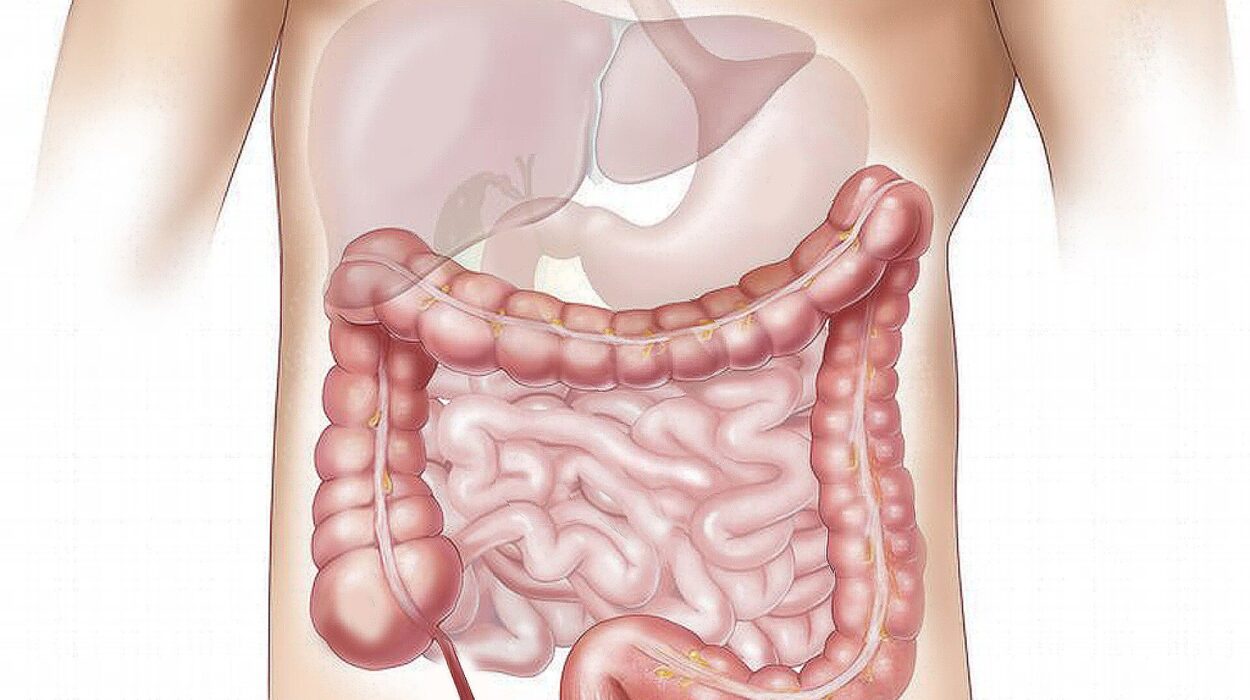

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Bladder problems such as interstitial cystitis

- Tingling or numbness in hands and feet

- Muscle stiffness, especially in the morning

This wide spectrum of symptoms contributes to the difficulty of diagnosis, as fibromyalgia overlaps with many other conditions.

The Challenge of Diagnosis

Diagnosing fibromyalgia can be a long and frustrating journey. Unlike many other disorders, there is no definitive blood test, imaging scan, or biomarker that confirms fibromyalgia. Instead, diagnosis is based on clinical evaluation, patient history, and the exclusion of other conditions.

The Old Criteria

For many years, diagnosis required the presence of widespread pain and tenderness in at least 11 of 18 specific “tender points” on the body. Doctors would press these points to determine if they triggered pain. While this method highlighted the widespread nature of fibromyalgia, it proved too restrictive and inconsistent—many patients with fibromyalgia did not meet the exact tender-point criteria.

The New Criteria

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) updated the diagnostic criteria. Diagnosis now focuses on the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and Symptom Severity Scale (SSS). Patients qualify if they report widespread pain across multiple regions of the body along with symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, and cognitive difficulties lasting at least three months.

Doctors must also rule out other potential causes of chronic pain and fatigue, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, thyroid disorders, or chronic fatigue syndrome. This process often requires extensive testing, which can be emotionally draining for patients already struggling with symptoms.

The Patient’s Experience

For many, the path to diagnosis is long and filled with frustration. Patients may see multiple doctors, undergo numerous tests, and face skepticism before receiving validation of their condition. Misdiagnosis and dismissal as psychosomatic are unfortunately common, adding to the emotional burden of the illness.

Treatment Approaches: Managing the Unmanageable

There is no cure for fibromyalgia, but treatment focuses on managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and helping patients regain control of their daily lives. Effective treatment often requires a multi-pronged approach, combining medication, lifestyle changes, and psychological support.

Medications

Several classes of medications are used to alleviate fibromyalgia symptoms:

- Pain relievers: Over-the-counter options such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs may provide mild relief, though they are often insufficient for severe pain. Prescription drugs like tramadol may be considered, but opioids are generally discouraged due to limited effectiveness and high risk of dependency.

- Antidepressants: Medications such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella) can reduce pain and improve mood by regulating neurotransmitters involved in pain processing.

- Anti-seizure drugs: Pregabalin (Lyrica) and gabapentin (Neurontin) are commonly prescribed to calm overactive nerves and reduce pain.

Non-Medication Therapies

Equally important are non-drug approaches that address the mind-body connection:

- Exercise: Low-impact activities such as swimming, walking, or yoga can reduce pain and improve function. Though exercise may initially worsen symptoms, gradual and consistent movement often leads to long-term improvement.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT helps patients reframe negative thought patterns and develop coping strategies for chronic pain.

- Physical therapy: Targeted stretching and strengthening exercises can relieve stiffness and enhance mobility.

- Sleep hygiene: Establishing consistent sleep routines and addressing underlying sleep disorders is vital.

- Mind-body practices: Meditation, tai chi, and mindfulness-based stress reduction have shown promise in easing symptoms.

Lifestyle and Self-Care

Diet, stress management, and pacing daily activities are essential. Patients often benefit from anti-inflammatory diets rich in fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and omega-3 fatty acids. Stress reduction through relaxation techniques, journaling, or hobbies provides psychological relief. Learning to pace oneself—balancing activity with rest—helps prevent flare-ups.

Support Systems

Support groups and counseling can provide validation, reduce isolation, and share coping strategies. For many patients, connecting with others who understand their struggles is as therapeutic as any medication.

Living with Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is not a life-threatening condition, but it is life-altering. It requires patients to adapt, to listen to their bodies, and to advocate for themselves in a medical system that does not always fully understand their needs. Many find strength in resilience, creativity, and building a lifestyle that accommodates their limitations while still nurturing their passions.

The emotional impact of fibromyalgia cannot be underestimated. Chronic illness can erode self-esteem, strain relationships, and foster feelings of isolation. But with comprehensive treatment and support, many patients lead meaningful, fulfilling lives. Advocacy movements and growing awareness are slowly transforming how society perceives this condition, offering hope for greater recognition and improved care in the future.

The Future of Fibromyalgia Research

Ongoing research is unraveling the mysteries of fibromyalgia. Advances in neuroimaging are providing deeper insight into how the brain processes pain. Scientists are exploring the roles of the microbiome, immune system, and genetics in shaping vulnerability to the disorder. Personalized medicine, tailored to an individual’s unique biological and psychological profile, may one day transform treatment approaches.

Pharmaceutical research is investigating new drugs that more specifically target central sensitization and pain pathways. Meanwhile, integrative medicine is exploring combinations of traditional treatments with alternative therapies such as acupuncture, biofeedback, and nutritional supplements.

As science progresses, one truth remains: fibromyalgia is real, complex, and deserving of compassion and attention. Patients are not imagining their pain—it is a legitimate medical condition that challenges our understanding of human health.

Conclusion: Beyond Pain, Toward Understanding

Fibromyalgia is more than just chronic pain—it is a disorder that reshapes how individuals experience life. Its causes are multifactorial, its symptoms diverse, and its impact profound. Though the journey to diagnosis can be long, and treatment is rarely straightforward, patients with fibromyalgia are not without hope.

The condition teaches us a broader lesson about health: that it is not merely the absence of disease but the harmony of body, mind, and spirit. Living with fibromyalgia requires resilience, self-compassion, and community support. It challenges the medical field to go beyond test results and listen deeply to patients’ experiences.

In the end, fibromyalgia is not just a story of pain—it is also a story of survival, strength, and the ongoing search for healing.