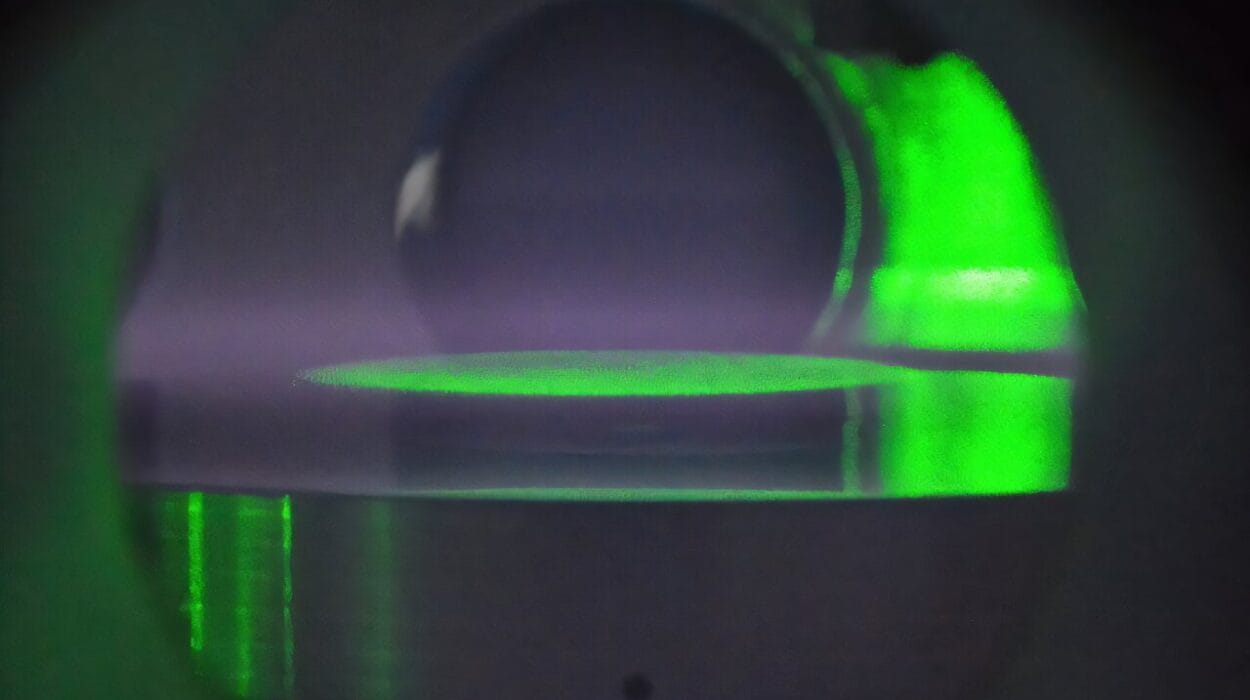

Inside laboratories where stars are mimicked and fusion fuel is squeezed by light, scientists face a peculiar problem. The material they study, plasma, is everywhere in the universe and yet maddeningly hard to listen to. It rushes, crackles, and reshapes itself in fractions of a second. For decades, researchers have tried to understand its inner state by catching the faintest echoes it gives off when struck by a laser. Those echoes are so quiet they are almost swallowed by noise.

This challenge sits at the heart of high-energy physics. If scientists want to understand how stars burn, how nuclear detonations unfold, or how fusion energy might someday be controlled, they need reliable ways to measure what plasma is doing in the moment. Temperature, density, motion, all of it matters. And until now, those measurements have often arrived as whispers.

A team at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has just turned that whisper into something closer to a shout.

The Old Way: Chasing Flecks of Light

For years, physicists have relied on a method known as Thomson scattering. The idea is simple in principle. Fire a single laser beam into plasma and watch how a tiny fraction of its light scatters off energized electrons. Instruments such as spectrometers capture that scattered light, and from its subtle changes scientists can infer the plasma’s temperature, density, and velocity.

In practice, it is brutally difficult.

Plasma is often described as the fourth state of matter, a superheated mix of free electrons and ions that behaves nothing like solids, liquids, or gases. When lasers hit it, the environment is chaotic. Only about one out of every billion photons sent into the plasma makes it back to the detectors in a usable way. Everything else is drowned in background noise.

“At facilities like the National Ignition Facility, knowing the conditions where all these lasers cross is really important,” explained experimental physicist Andrew Longman. Those conditions influence how energy moves between beams and whether an implosion stays symmetric. Yet measuring them has remained a struggle.

Even with sophisticated systems like NIF’s Optical Thomson Scattering Laser System, the signal remains weak. As physicist Pierre Michel put it, what scientists often measure is “really like enhanced noise from the plasma, but it’s very tiny.” Experience and finesse help, but the technique leaves little room for error.

A Strange Idea Begins to Glow

Several years ago, a different possibility began to take shape, almost as a side thought. Michel and then-student Joshua Ludwig were studying crossed-beam energy transfer, or CBET, a process already used at NIF to fine-tune how energy flows between overlapping laser beams.

When NIF fires up to 192 laser beams into a small hollow cylinder called a hohlraum, those beams overlap and exchange energy as they enter. The resulting bath of X-rays drives a peppercorn-sized fuel capsule toward fusion. CBET had become a useful control knob for adjusting energy balance during implosions.

But Ludwig and Michel kept tugging at the theory behind it.

What if that energy exchange could do more than adjust beams? What if it could also reveal the plasma’s internal conditions?

They followed the math. Ludwig ran simulations using the Lab’s most advanced tools. The results suggested something surprising. The interaction of two crossed beams might carry rich information about the plasma, information that could be measured directly.

“It should work in an experiment,” Michel recalled. At the time, that idea lived mostly on paper.

One Shot, Two Beams, Everything at Once

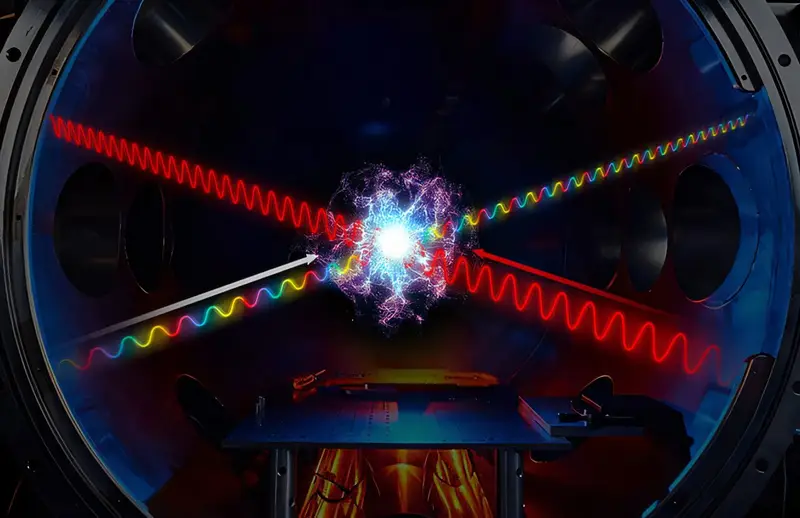

The new approach flips the old logic on its head. Instead of relying on a single beam and hoping for scattered photons, the technique uses two laser beams that intentionally cross inside the plasma.

One is a strong pump beam aimed into the plasma. The other is a weaker probe beam that intersects it. Crucially, the probe beam carries a broadband spectrum, meaning it contains many closely spaced wavelengths of light.

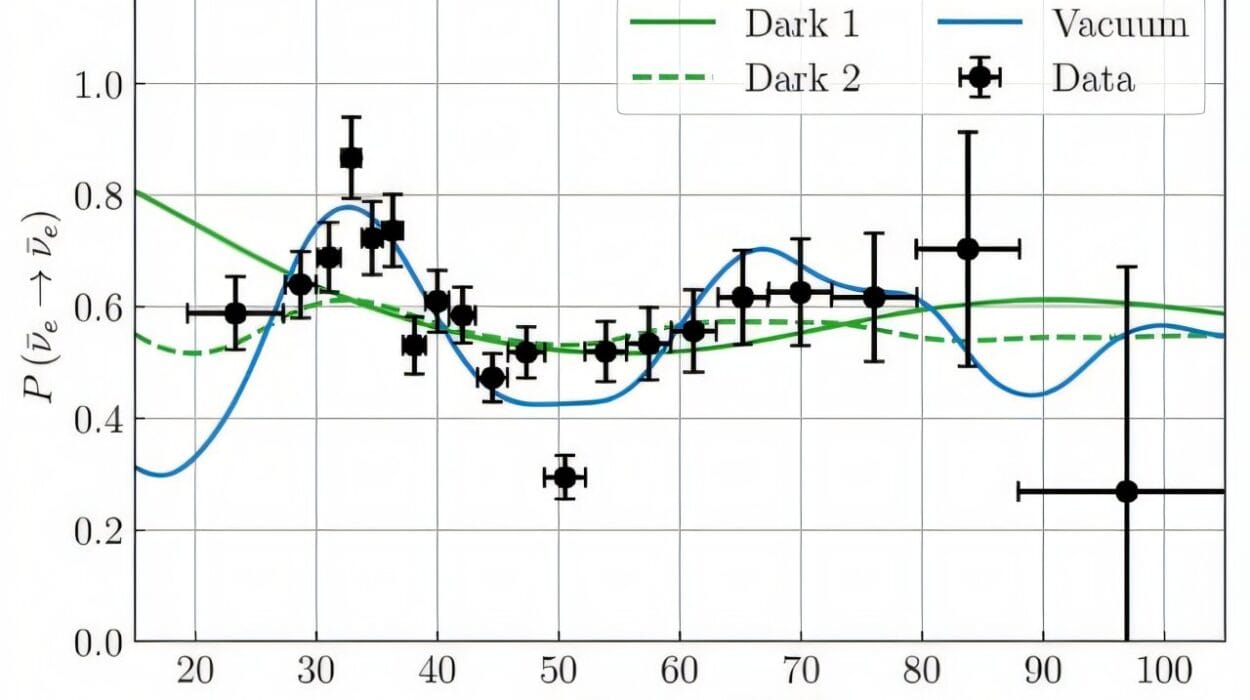

As energy transfers from the pump beam to the probe beam through CBET, the plasma leaves its fingerprints on that exchange. Those fingerprints encode information about temperature, density, and flow. And because the probe beam already contains a wide range of wavelengths, it can capture many plasma characteristics at once.

With Thomson scattering, scientists may need multiple experimental shots to study different properties. At a facility as busy as NIF, that time is scarce, and plasma conditions can vary from shot to shot. The crossed-beam method, by contrast, delivers a comprehensive picture in a single shot.

Even more striking is the signal strength. The data coming back from this method is more than a billion times stronger than what Thomson scattering typically provides. What once required squinting through noise now arrives blazing bright.

A Tool That Wouldn’t Exist Without STILETTO

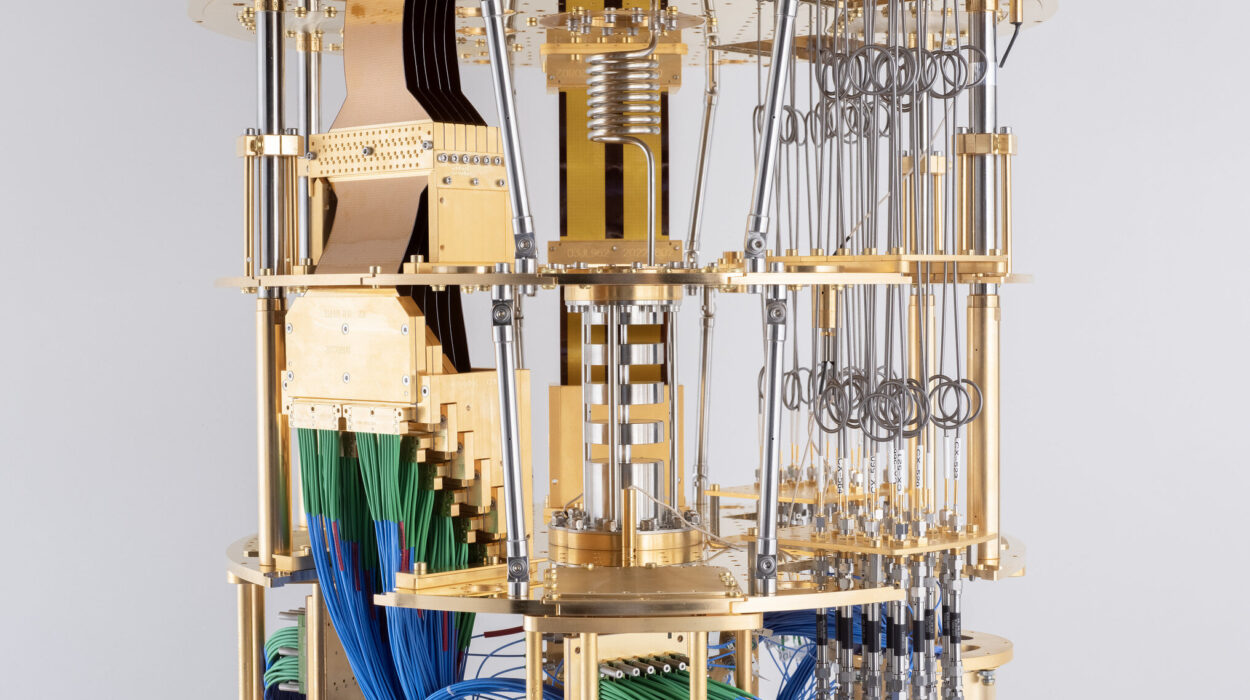

For years, the idea remained untested. The equipment needed to shape and control the probe beam simply didn’t exist in the right form. That changed during a four-year refurbishment of LLNL’s Jupiter Laser Facility.

One of the major additions was a laser pulse-shaping technology called STILETTO, short for Space-Time Induced Linearly Encoded Transcription for Temporal Optimization. Invented at LLNL, STILETTO allows researchers to sculpt laser pulses in exquisitely precise ways, adding bandwidth and shaping their structure.

When Longman joined the Lab in 2021, he became part of the team implementing STILETTO at Jupiter. He saw an opportunity to finally put the crossed-beam theory to the test. Designing the experiment was not trivial. The probe beam had to match the wavelength of the drive lasers while also carrying significant bandwidth. That combination demands specialized tools.

This experiment would be the first ever to use STILETTO.

Too Much Light Is a Good Problem to Have

Setting up the experiment took six to seven weeks of careful tuning. Longman described it as searching for a “magical recipe.” Then, when the beams crossed and the detectors turned on, the team realized something extraordinary.

The signal was overwhelming.

“So bright that we had to filter it down by about a factor of 10,000 just so it wasn’t blinding the camera,” Longman said. In plasma diagnostics, that sentence borders on unbelievable. Usually, the problem is a lack of light. Here, there was far too much of it.

Unlike Thomson scattering, where nearly all incoming photons vanish into the plasma, the CBET-based method allows all the incoming photons to be directly collected. The probe beam’s lower power also meant it did not disturb the plasma it was measuring, a crucial requirement for accurate diagnostics.

The proof of principle worked beautifully.

Simplicity Where There Was Once Finesse

One of the most striking outcomes was not just the brightness of the signal, but the relative ease of the setup. Thomson scattering often fails in practice because it demands exceptional experience and delicate adjustments. Many experiments never quite reach the sweet spot.

By contrast, Longman and his colleagues demonstrated the new method in just seven weeks, from setup to success. That speed hints at how accessible the technique could become.

At NIF, implementing it could be straightforward. The pump beam would already be present, matching the wavelength of the implosion-driving lasers. Aiming the probe beam, Longman said, is “just like pointing a red laser pointer across the room and aligning it into a spectrometer.”

“Almost everyone can do that,” he added.

When Team Science Clicks

Both Longman and Michel emphasize that the experiment’s success was deeply collaborative. Physicists developed the theory. Laser physicists designed and built STILETTO. Technicians and facility staff at Jupiter supported the work. Each piece depended on the others.

Michel praised Longman’s experimental design, noting that such clean success on a first attempt is rare. “Usually, when you try something like that in an experiment, it takes a few tries until it actually works,” he said. This time, it did.

The results were published in Physical Review Letters, marking a milestone for a concept that began as a theoretical curiosity.

Why This Breakthrough Matters

This new technique is not meant to replace Thomson scattering. Instead, it offers something equally valuable: a powerful, complementary way to see into plasma when time, precision, and clarity matter most.

For researchers working in high energy density science and inertial confinement fusion, especially at places like the National Ignition Facility, the ability to measure plasma conditions accurately in a single shot could change how experiments are designed and interpreted. Stronger signals mean less uncertainty. Single-shot diagnostics mean fewer assumptions about what changed between experiments.

Beyond the technical benefits lies something more fundamental. Plasma governs the behavior of stars, the physics of fusion, and some of the most extreme environments humans can create in a laboratory. Every improvement in how we measure it brings those distant, violent, beautiful processes a little closer to understanding.

For decades, scientists strained to hear plasma whisper. Now, with two crossing beams of light, it is finally speaking up.

Study Details

A. Longman et al, Pump with Broadband Probe Experiments for Single-Shot Measurements of Plasma Conditions and Crossed-Beam Energy Transfer, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/96yh-96pw. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2508.11156